Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

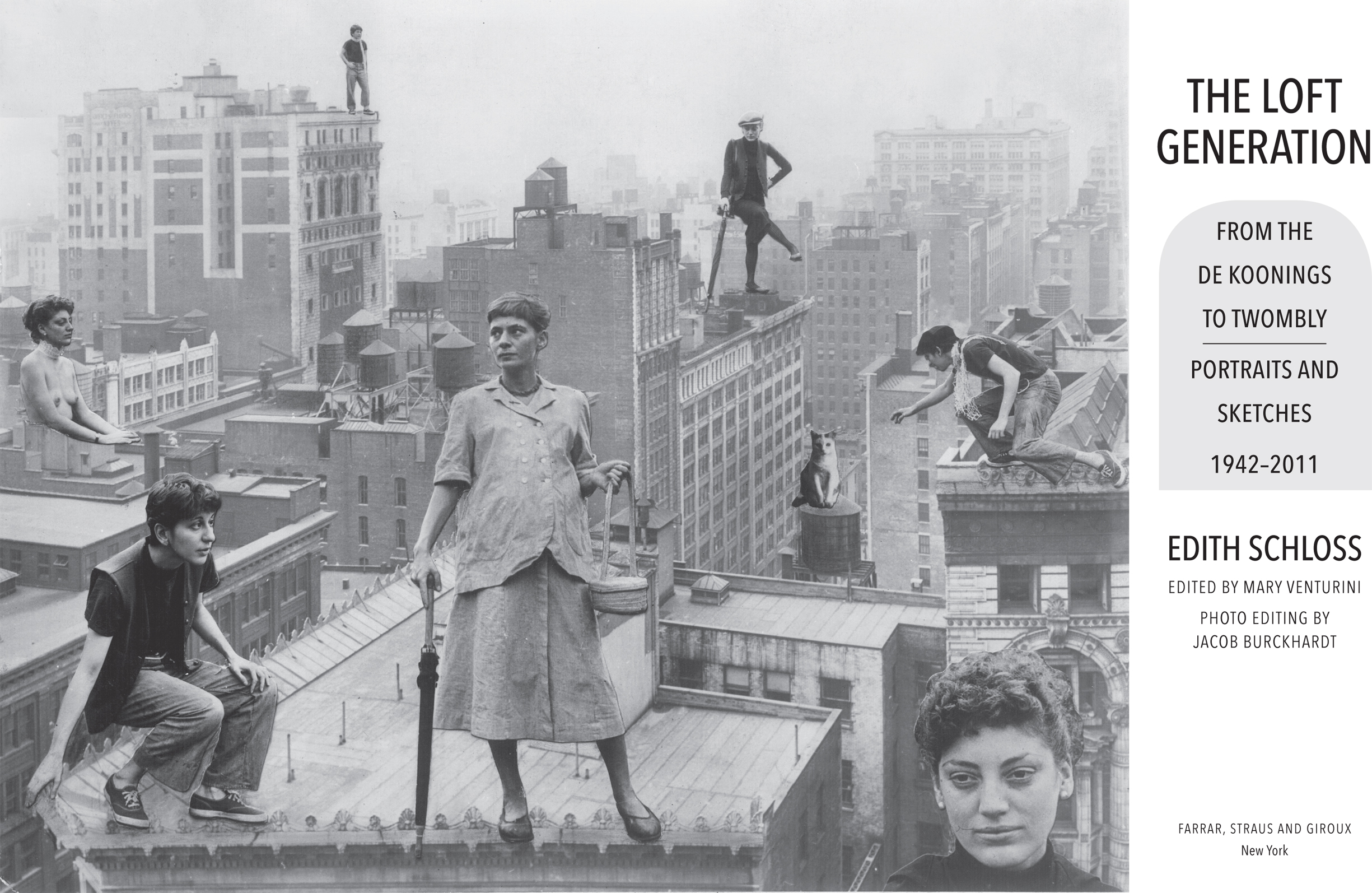

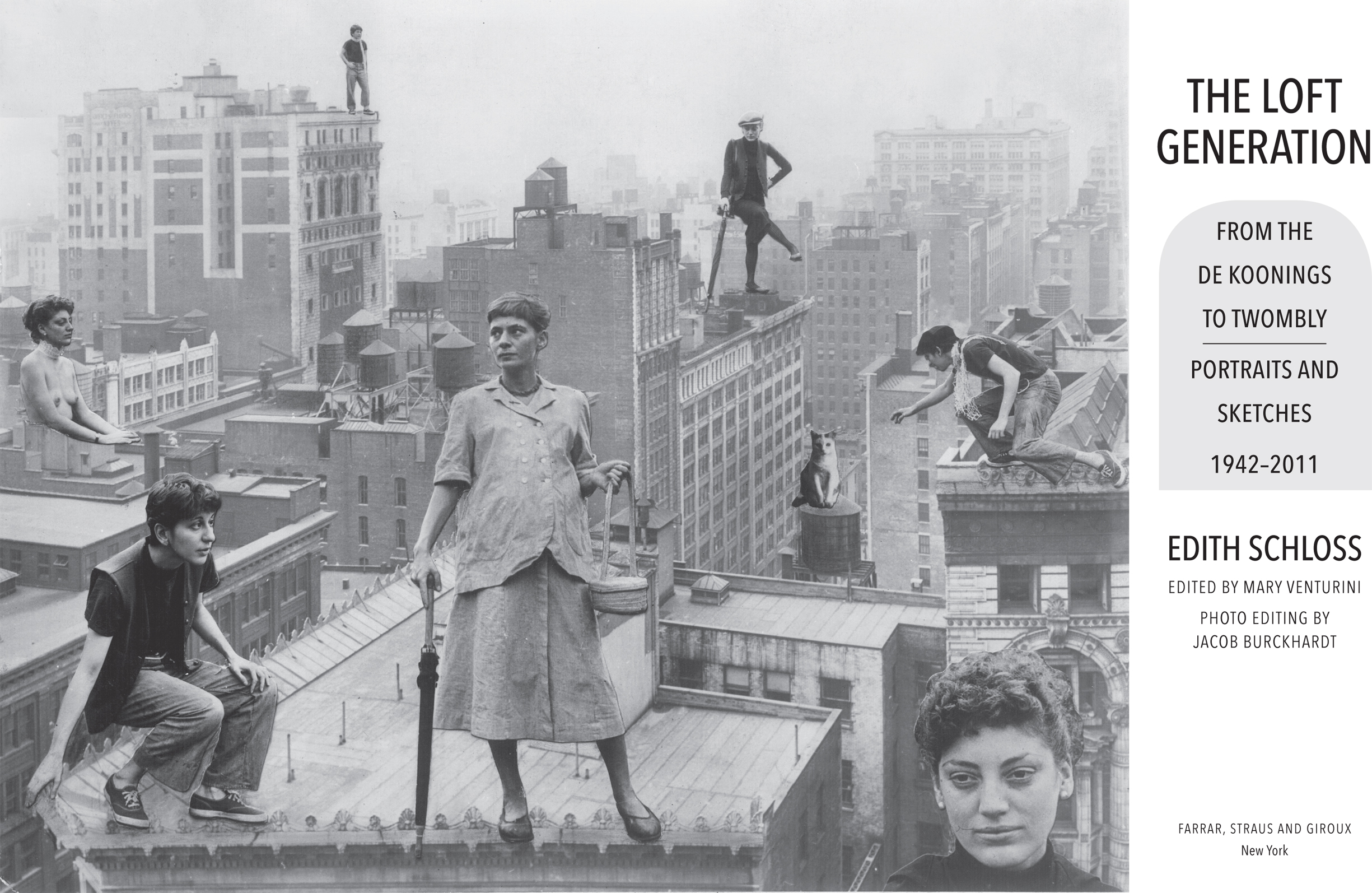

Edith Schloss could not decide whether she was a painter who writes or a writer who paints. In any case, she was an accomplished writer who wrote many art reviews and memoirs about various people she knew and events in her life. She also wrote at least one unpublished novel.

Usually she began a project by scribbling notes on pieces of paper. Next she would hammer out a draft or two on her Olivetti Lettera 22. She would cut up those drafts and paste the fragments onto clean sheets of paper in new arrangements, writing corrections in the margin or between lines until the final polished version was ready.

When she died, she left many manuscripts in various stages of completion, all the way from folders full of scraps of paper to clippings from publications. The Loft Generation was in the form of an early draft.

Although New York is the main location of the memoirs, Italy also had an important influence on Ediths work even before she went to live there in 1962. Many of the friends she made in New York among artists, musicians, and poets in the 1940s and 1950s subsequently arrived in Rome for exhibitions or concerts, or as visiting fellows at the American Academy. Many of the exhibitions she reviewed and the feature articles she wrote when she was living and working in Rome drew on her formation and background in New York before she left for Rome.

This double influence is reflected throughout her writing, as well as in her painting. Therefore some of the articles she wrote during the five decades she lived in Rome, which were not included in the early draft of her memoirs, have been included in The Loft Generation.

Ediths memoirs are often inspired by people, places, exhibitions, concerts, and, sadly, the deaths of her friends. So readers should not expect the usual historical narrative of the genre, but rather a series of portraits and sketches, evidence in itself of how Ediths eye as a painter influenced her work as a writer.

Three editors worked on the initial draft of The Loft Generation: Annabel Lee, Simon Pettet, and me. Our principal tasks were correcting errors relating to names, dates, and places; eliminating redundancies; proofreading; and research. My own memory was a key resource. Simon Pettet reviewed the manuscript in its earliest stage and did copyediting and fact-checking. Annabel Lee and I then did a comprehensive proofread and copyedit of the manuscript, a critical close reading, and further revisions in order to hold to Ediths original as accurately as possible after initial corrections had been made. The final draft was edited by Mary Venturini, who was Ediths editor at the magazine Wanted in Rome from the mid-1980s until her last article, which featured Cy Twombly and was incomplete at the time of her death, in December 2011. Twombly, who died in Rome only a few months before Edith, became as much of an influence on her later work as both Willem de Kooning and Fairfield Porter were earlier.

At the end of the book the reader will find a glossary of the names of those in the book, with brief biographical profiles; as well as a list of the images included and their sources.

Many people have generously advised, assisted, and supported us in our research and in other ways, including Jason Andrew, John Ashbery, Dore Ashton, Mariateresa Barbieri, Jacopo Benci, Hugh Burckhardt, Steve Clay, William Corbett, Robert Cornfield, Betty Cuningham, Alvin Curran, Tom Damrauer, Mary Daniels, Rackstraw Downes, Hermine Ford, Mary Gabriel, Mimi Gross, Haidee Becker Kenedy, Albert Kresch, Elizabeth Kresch, Laura Kuhn of the John Cage Trust, Susan Levenstein, Phillip Lopate, Julie Martin, Barbara Mayfield, Ron Padgett, Peter Rockwell, Gary Roth, Fred Schloss, Ruthellen Schloss, Justin Spring, Silvia Stucky, the Cooper Union, Zelda Wirtschafter, and Nathan Kernan and Thomas Whitridge of Ink, Inc.

For illustrations, many individuals and organizations have been generous, including John Cohen and L. Parker Stephenson, the Artists Rights Society, Eric Brown, Andrew Arnot, the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, the Art Students League, Katie and Elizabeth Porter on behalf of the Estate of Fairfield Porter, Yvonne Jacquette and Tom Burckhardt on behalf of the Estate of Rudy Burckhardt (of which I am part), Shari Steiner, David Carter, the Wadsworth Atheneum, Paul Linfante, Thomas Micchelli, Alex Katz, Vincent Katz, Colby College, Yoshiko Chuma, David White of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, and David Joel of the Larry Rivers Foundation.

Conversations with Giorgio Morandi was first published as You Can Paint Anything If You Want To in 891 international artists magazine in 1986, and Francesca Woodman was published as The Fierce Poetry of Francesca Woodman in 2000 in the magazine Italy, Italy. The article on Cy Twombly was published in Wanted in Rome in 2012, after Ediths death.

To anyone who has been inadvertently left out of these lists, we thank you as well and profusely apologize.

New York, 2021

One fine summer afternoon in 1961, the artist and writer Edith Schloss sets out alone, without appointment or introduction, on a pilgrimage to visit the painter Giorgio Morandi in the mountain village in the north of Italy where he has a summer home. On the way, she stops to pick wildflowers along the dusty roadside, when she becomes aware that someone is looking at her through a spyglass from the upstairs window of a house above her.

It is, of course, Morandi, who then welcomes her into his home. One senses that he has espied through his glass not just a lovely woman but also a keenly observant spirit akin to his own, one taking as intense a delight in nature as she does with everything she sees in his home. Schlosss driving interest in art and her quality of openness and detailed attention to what comes her way underlie The Loft Generation, her memoirs of her years in the New York art world in the 1940s and 1950s and of the many important artists, writers, poets, and composers she knew well in the five decades she was active in the arts in America and Italy.

The Abstract Expressionist era and the New York art world after World War II to the 1960s are among the more thoroughly discussed, analyzed, documented, and canonized periods in art history. The number of meticulously researched major museum exhibition catalogues, biographies of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, histories, critical analyses, as well as memoirs by the art critic Irving Sandler and collected writings by artists of the period such as Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Jack Tworkov, and Mark Rothko, would make it seem like a time from which there is nothing left to excavate. And yet in The Loft Generation, Schloss opens doors to some of the most iconic spaces of this history and brings her reader inside in a way that is perhaps the closest to the experience of what it would have been like to be there, as observed by a very perceptive, intelligent person with incredible recall, gifted with an excellent visual, literary, and narrative memory.