Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form, and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

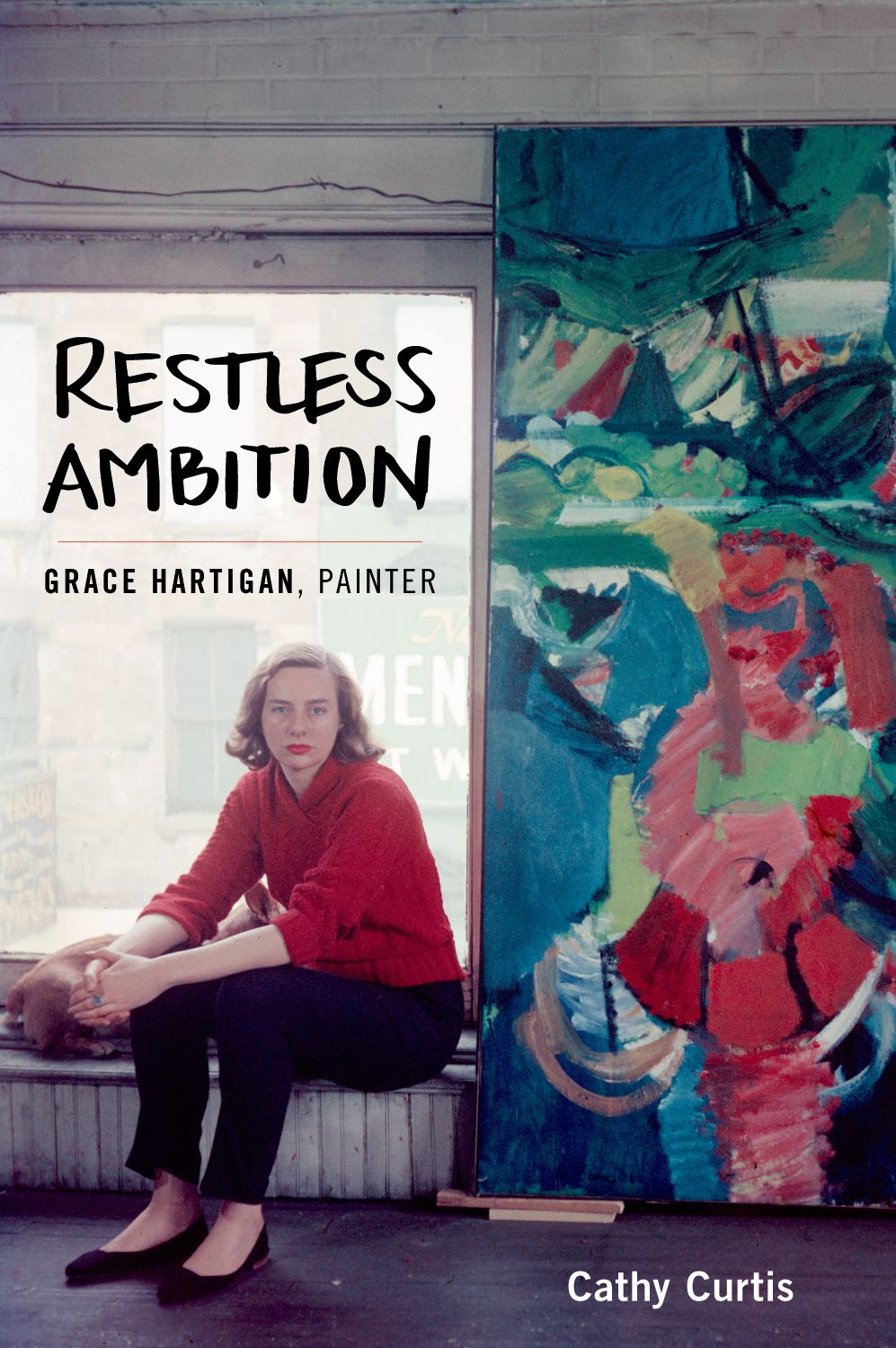

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Curtis, Cathy (Writer on art) Restless ambition : Grace Hartigan, painter / Cathy Curtis.

pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780199394500 (alk. paper)

1. Hartigan, Grace. 2. PaintersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Women paintersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title. ND237.H3434C87 2015 759.13dc23 [B] 2014020233

when i met grace hartigan she came out to California in 1988 for the opening of The Figurative Fifties, a museum exhibition that included paintings of hers from the 1950sshe was an earthy and voluble sixty-six-year-old woman, enjoying a second hurrah of renown. I was a young cultural reporter and art critic at the Los Angeles Times, pleased that her chattiness was making my job so easy.

Sitting on her sunny hotel balcony, Grace talked about how, when she was thirty-one and her painting The Persian Jacket was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, she no longer had to live on oatmeal and bacon ends. About how odd it was to see a photograph of herself in Newsweek in 1959, across the page from a shot of Judy Garland. And about how, although she considered herself an Abstract Expressionist, she felt absolutely free to use recognizable images in her work. You dont live a category, she said. You were just hanging out with a lot of interesting people.

Fast-forward to October 2010. Visiting the Museum of Modern Art on a trip to New York, I rounded a corner at the Abstract Expressionist New York exhibition and came face to face with a nearly eight-foot-tall painting. I was stunned at the power and beauty of its slashing blocks of vivid colora work that held its own among canvases by the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Peering at the label, I saw that this was Shinnecock Canal (plate 11), painted by Grace in 1957.

Who was this woman who had shouldered her way to the top of the male club that was the New York art world of her era? How did she get there, and why did she fall so abruptly off the art map? Always fascinated by biography, I was avidly reading obituaries in search of someone whose life combined great achievement with a complex, intriguing personality. Now I had finally found her.

I called Paul Schimmel, chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles. He had co-organized The Figurative Fifties at what was then the Newport Harbor Art Museum. What did he think about my writing a biography of Hartigan? Very good idea, he said, giving me a list of key art-world people to contact.

I discovered that Grace had entered adulthood with no goals except to escape her family. But once she became a painter, her self-regard and ferocious drive colored her relationships with the men she loved and the women she held at arms length, and caused a fatal breach with her only child.

Although Grace lived to be eighty-six, I decided to devote nearly half of this biography to the 1950s, the decade of her finest paintings, when she managedagainst great oddsto carve out a major career in New York. In dealing with this period, I broadened my focus to look at the personalities and achievements of those interesting people Grace hung out with and at the ways her life both resembled and differed from that of other women painters in her circle.

I came to understand that Graces professional life was a roller-coaster of struggle, triumph, neglect, and rediscovery, while her personal life was blighted by alcoholism, romantic missteps, and personal tragedy. Yet she never stopped believing in her talent and her vision. Alone, in the studio, she spent her finest hours.

A Note About the painting reproductions in this book: Some of the works I discuss at length are not included among the color plates. There are several reasons for this, including the unavailability of certain images, overly restrictive reproduction stipulations, and the need to limit book production costs.

Restless Ambition

from her unseen perch in a flowering apple tree, Grace Hartigan spied on the gypsy families whose caravans were parked in an empty field next to her homean exotic sight in the 1930s in placid Millburn, New Jersey. Grace wanted to be a detective when she grew up, but her stakeout was driven by sheer visual delight. She yearned to make friends with these fascinating people, but her mother, muttering darkly about gypsies stealing children, had forbidden any contact.

decades later, grace would trot out versions of this story as the defining feature of her youth. The gypsies stood for a tantalizing otherness and for everything her middle-class family found alien and threatening. When she discovered the gypsies, Grace was living with her parents, two younger sisters, and baby brother in a two-story house with a neat stretch of lawn at 527 Wyoming Avenue. The broad, curving street was part of South Mountain Estates, a spacious new subdivision just five blocks from Taylor Park. Grapevines stretched along one side of the house and a patch of violets grew in back of the garage.

Millburn was a step up from the two-family house in Bayonne, New Jersey, squeezed next to its neighbors a half-block from Newark Bay, where Graceborn in Newark on March 28, 1922had spent the first seven years of her life. Multi-family homes like Graces accommodated an immigrant population accustomed to living with their extended families. Before his marriage, Graces father, Matthew, had lived in Bayonne with his Irish-born parents. Working as an assistant foreman at Babcock & Wilcox, a large boiler manufacturing company, he claimed an exemption from the World War I draft at age twenty-five because he was their sole means of support.

Many of Bayonnes residents were immigrants toiling in the silk, cotton, and wool mills, at Standard Oil of New Jersey, and in more than seventy factories that produced chemicals and industrial components. City life was colorful and cacophonous in the 1920s. Women carried their shopping in baskets and jugs, as they did in the Old Country, and vendors broadcast their wares through megaphones: Watermelons! Roasted peanuts! Heeeere peaches-tomatoes-potatoes heeere! (Decades later, Grace would be enchanted by a similar environment in the pushcart throngs of Manhattans Lower East Side.) Newark Bay offered scavengers treasures and fiddler crabs hiding under rocks at low tide. In winter, there was ice skating on Hudson County Park pond.