Contents

About the Book

Is it too late to get help? he asked me.

Its gone beyond that, I told him bluntly.

He was quiet then, taking that in.

And then said, Do you want another one?

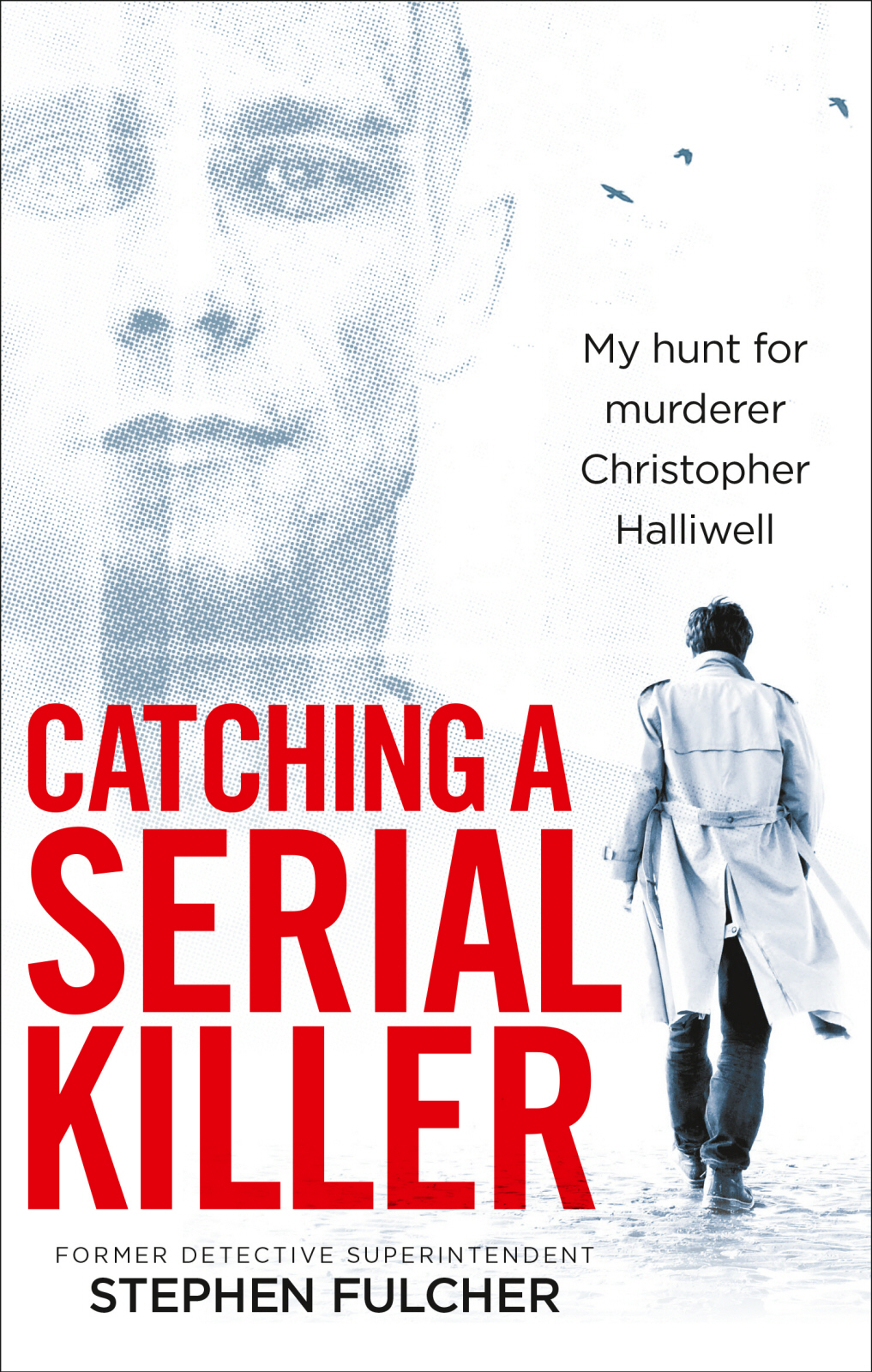

On the evening of Saturday, 19 March 2011, Detective Superintendent Stephen Fulcher received a life-changing call that thrust him into a race against time to save a missing 22-year-old girl. What followed was an intense investigation and a cat-and-mouse pursuit that led Steve to the discovery of two bodies.

Catching a Serial Killer is a thrilling and devastating look at a real-life murder case and potentially one of the UKs most prolific serial killers.

About the Author

Stephen Fulcher was born and bred in Coventry. He joined the police force in 1986 and rose through the ranks to become a detective superintendent, working for Sussex CID, Special Branch at Gatwick and the Force Intelligence Bureau before joining Wiltshire Police in 2003. During his time in the force he helped solve countless major crime cases, leading many as the senior investigating officer, and received three crown court commendations and one chief constables commendation. He holds a masters degree in applied criminology and police management from Cambridge University.

Having now left the police force, Steve works with UK government agencies, training local police officers in political hotspots such as Libya and Somalia.

This is his first book.

To Sian and Becky,

and the girls who havent been found

Rules are for the guidance of wise men

and the obedience of fools.

Harry Day,

Royal Flying Corps fighter pilot (18981977)

Prologue

Friday, 3 January 2003

The steady thrum of music from the Destiny & Desire nightclub could be heard even on the street outside. It seemed to pound through the pavement, pound in time with the girls heartbeats as they stood there chatting, their noses nipped by the cold night air.

As the two young women waited on the street, a cars engine joined the cacophony: another noise to add to those irking the residents who lived nearby, who complained that the nightspot was the bane of their lives. Yet the engines purr soon faded as the car pulled up smoothly next to the kerb. The driver, unseen in the shadows, beckoned one of the young women to his side.

She went, somewhat unwillingly, and was clearly not interested in whatever it was he had to say. She returned quickly to her friend, perhaps with a toss of her bright blonde hair, leaving the man to his own devices. The new hope of the New Year was still tangible in those first few days of January 2003 and auld acquaintances, in some cases, were best forgotten, after all.

But the driver disagreed. The silver Volvo stayed unmoving at the side of the street, so the young woman once again went to speak with the man behind the wheel.

At 20 years of age, she was a gentle character, yet she also had a reputation for being feisty when she needed to stand her ground. Her petite frame she was only four foot eleven belied her strength of character. It wasnt long before a row erupted: raised voices disturbing the sleep of those beleaguered neighbours who had been disturbed too many times before to bother looking out of their windows to spy the source of this latest commotion. They didnt see the girl shouting through the Volvos window or storming back to her friend or the way the car remained, despite all this, by the side of the road, its presence commanding and insistent, its driver unswayed by the wishes of the woman.

She had said no once. She had said no twice. But, the third time, she told her friend she was leaving, shrugged her shoulders in a huff and slipped hurriedly inside the rear of the vehicle, slamming the door shut behind her.

It closed with a decisive click: a punctuation point to mark the end. The car pulled swiftly away, its tail lights glowing red in the dark. With a final burst of acceleration, it rounded the corner and vanished from sight.

Friday, 18 March 2011

Night, guvnor.

Looking up from my desk, I raised a hand in farewell as my colleague ducked back out of my office and went whistling away down the corridor, the jauntiness of the melody signalling his delight at getting out of the nick relatively early on a mild spring Friday night.

I turned back to my computer with a sigh: there would be no such early doors exit for me. As director of intelligence for Wiltshire Police, I had my work cut out I was responsible for all intelligence across the entire force, with a particular remit for fighting organised crime. I was often the last one out of Wiltshire Police HQ on a Friday evening.

As I settled into my work, however, I found the time passed quickly. Much as I often narked on about the constant cuts or the tedious politics of modern-day policing, the truth was I loved my job. Id been a copper since 1986, starting out as a bobby on the beat in a big hat and boots; Yvonne, then my girlfriend, had told me Id have to become a detective as I looked utterly ridiculous in the uniform. But I didnt need any urging: almost from the moment I joined the force I wanted to deal with proper crime and make a real difference. I liked serving the public and trying to do my best for them, and I felt best placed to do that in CID, where I earned my stripes as a young detective from the age of 23.

The funny thing about policing is that it starts out as a job like any other: youre working to live. Somehow, though, over the years particularly for detectives, I think that equation turns on its head and you live to work: the job becomes the life. Being part of the police force in some ways is like being part of a family, and I relished the teamwork and the camaraderie, that sense of pulling together to bring in a result. Even though there seemed to be more and more bureaucracy the higher I climbed moving first from constable to sergeant, then to inspector, and finally, in 2007, to the heady heights of detective superintendent I still lived for the cut and thrust of operational policing. Detective superintendent was the highest rank for that and now, aged 44, I wasnt sure I had the appetite or the inclination to climb any higher, for it would mean leaving the real job behind. In addition to my role as director of intelligence, I headed up major crime enquiries as an SIO (senior investigating officer). That involved the intellectual challenge and down-and-dirty work of solving crimes and bringing offenders to justice and those aspects of the job motivated me like nothing else.

Sat at my desk in HQ, I yawned widely and checked my watch: nearly 7 p.m. I smiled wryly to myself; our chief constable, Brian Moore, had a well-worn catchphrase There are two seven oclocks in every day and I expect you there for both of them and it seemed I was destined to fulfil his mandate once again. I gazed around my office as my ancient computer started its laborious process of shutting down for the night.

The intelligence team resided in the bowels of Wiltshire Police HQ: hot-water pipes ran all through the department, a less-than-glamorous backdrop to the filing cabinets and whiteboards of our trade. As my screen flickered to black, I found my gaze resting on the noticeboard beside my desk. It was where I kept bits and pieces from old cases personal items that wouldnt end up in the official files, such as notecards or thank-you letters and my eye was caught by a womans smiling face on an order of service. She was a murder victim; one of the more recent cases that Id solved. Id attended her funeral and pinned the booklet to the board afterwards; I couldnt tell you why, really, other than that it never seemed right simply to chuck them away. I guess her presence there, by my side every day, was a worthy reminder of why I did the job.