Samuel Fuller: Interviews

Conversations with Filmmakers Series

Gerald Peary, General Editor

Samuel Fuller

INTERVIEWS

Edited by Gerald Peary

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member

of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2012 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2012

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fuller, Samuel, 19121997.

Samuel Fuller : interviews / edited by Gerald Peary.

p. cm. (Conversations with filmmakers series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61703-306-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61703-307-0 (ebook) 1.

Fuller, Samuel, 19121997Interviews. I. Title.

PN1998.3.F85A3 2012

791.430233092dc23 2011044957

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

William R. Weaver / 1949

James Bacon / 1958

Stig Bjorkman / 1965

Eric Sherman and Martin Rubin / 1968

Ian Christie et al. / 1969

Dominique Rabourdin and Tristan Renaud / 1974

Richard Thompson / 1976

Russell Merritt and Peter Lehman / 1980

Russell Merritt / 1980

Gerald Peary / 1980

Tom Ryan / 1980

Noel Simsolo / 1982

Don Ranvaud / 1982

Richard Schickel / 1982

Hubert Niogret, Michel Ciment, Philippe Rouyer, Jean A. Gili / 1988

Franois Guerif / 1988

Introduction

Pickup on South Street, Verboten!, Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss. Do these loopy film titles mean anything to you? For a committed Fullerite, those four works with risible names, all produced on miniscule B budgets, are undisputed masterpieces, a quartet of American classics. And for the uninitiated public? To state the obvious, the late Sam Fuller, ace filmmaker, isnt for everybody, or probably most people. And being cultured and educated might just get in the way.

Fuller, who made twenty-three features between 1949 and 1989, is the very definition of a cult director, appreciated by those with a certain bent of subterranean taste, a penchant for what Manny Farber famously labeled as termite art. The French critic Luc Moullet explained, In Fuller, we see everything that other directors deliberately excise from their films: disorder, filth, the unexplainable, the stubbly chin, and a kind of fascinating ugliness in a mans face.

Artsy, yes, but not in an obvious, palatable way.

Youve got to appreciate low-budget, pulpish genre films, including westerns and war movies, and make room for some hard-knuckle, ugly bursts of violence. Youve also got to make allowance for lots of broad, crass acting, and scripts (all Fuller-written) which can be stiff, sometimes campy, sometimes laboriously didactic. And if your aesthetic requires a positive person in the narrative to root for? Opt for a less irregular director. I Shot Jesse James (1949), Fullers first feature, for which he was writer-director, set the stage for an abiding interest in dramatizing the lives of the fatally damned, the certifiably psychopathic. His hero, Bob Ford, is the dirty little coward who plugged Jesse in the back, and then, on stage, reenacted the sleazy murder for fame and money.

Fullers protagonists are, most often, creepy and off-putting, paranoid

So who speaks for Sam Fuller, and his very strange oeuvre? Film critics around the world. Even more, filmmakers. There has never been a B director who has been so embraced, and revered, by A-level cineastes. From the 1960s until his death in 1997, he was befriended by an amazing conglomerate of directors. Among them: Jim Jarmusch, Sara Driver, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Jonathan Demme, Peter Bogdanovich, Curtis Hanson, Quentin Tarantino, Francis Ford Coppola, John Cassavetes, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Franois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard.

It was a great kick for filmmakers, hanging with the crusty old storyteller. Much more important, his cinema amazed them. Fuller put the punch back into movies, shooting and cutting in wild ways that surprised even the most mannered, self-consciously formalist filmmakers.

Credit Fullers early employ as a New York crime reporter for giving him a unique slant on making cinema. He saw the motion pictures as a boiling-hot medium in line with the excitement of a tabloid front page: bold headlines, sensational photographs, lurid leads. His filmmaker peers responded to the yellow-journalism audacity of Fullers imagery: the shot from the gravePOV of a dead manin Forty Guns, the sordid attack of the nymphos in Shock Corridor (1963), the bizarre bald hooker in The Naked Kiss (1964). Grab the audiencethat was Fullers credo. As he put it in his famous cigar-chomping cameo in Godards Pierrot le fou (1965): Film is like a battleground love, hate, violence, death. In a single word: emotion.

Godard readily acknowledged that he lifted an extreme close-up of a revolver in Breathless (1959) from a bold shot in Fullers western, Forty Guns (1957). And Truffaut, soon after making The 400 Blows (1959), wrote of Fullers Verboten! (1959), I realize I still have to learn how to dominate a film perfectly, to give it rhythm and style, to bring out the poetry as simply as possible without forcing it. I shall go to this film again because I always come away from Sam Fuller films both admiring and jealous.

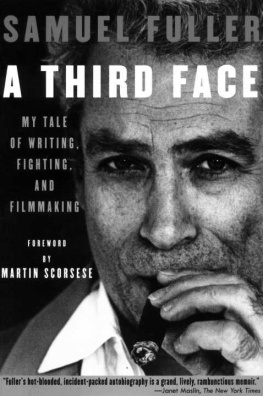

Over forty years later, in an introduction to A Third Face, Fullers 2002 posthumous autobiography, Martin Scorsese discussed his indebtedness. I loved Sam as a filmmaker, Scorsese said, and its impossible for me to imagine my own work without his influence and example. (Isnt Taxi Drivers violent, estranged Travis Bickle a refugee from the Fuller universe?) Where others saw flaws, Scorsese saw sinewy strength. Sure, Sams movies are blunt, pulpy, occasionally crude, lacking any sense of delicacy or subtlety. But those arent shortcomings. Theyre simply reflections of his temperament.

For Scorsese, theres nothing amiss with Fuller. I think if you dont like the films of Sam Fuller, than you dont like cinema, he asserted. Or at least you dont understand it.

Scorseses point has merit. Fuller is a cinematic director above all, deftly combining orchestrated long takes and elegant tracking shots with sudden, brash montage jolts: idiosyncratic cuts, feverish close-ups. Phil Hardy, author of the 1970 book Samuel Fuller, tried to explain: Just as violence is at the core of Fullers world, so his style centers on the violent yoking-together of disparate elements. The essence of Fullers style lies in creating dramatic confrontations by disrupting the spatial unity of a scene; the sacrifice of external naturalism to internal landscape. Fullers treatment of his world always makes of it an interior landscape through which his characters trek.

But how did Fuller come to have such a startling filmic vision? He was a high school dropout whose training was in journalism, not movie-making. His most deeply felt experience was being a soldier fighting World War II.

The prism by which many critics have understood Fuller is in classifying him as a primitive, an outsider artist. A Henri Rousseau, perhaps, a genius naf.

The primitive branding started in a 1959 essay by Luc Moullet in Cahiers du Cinma, and, in 1960, Truffaut affirmed it in the same periodical. It traveled to the US via Andrew Sarris in the seminal 1963

Next page