ALSO BY SAMUEL FULLER

Cerebro-Choc (Brainquake)

Pecos Bill et le Kid Cavale (Pecos Bill and the Soho Kid)

Quint's World

The Big Red One

Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street

144 Piccadilly

Crown of India

The Dark Page

Make Up and Kiss

Test Tube Baby

Burn, Baby, Burn

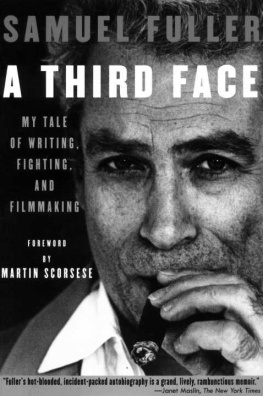

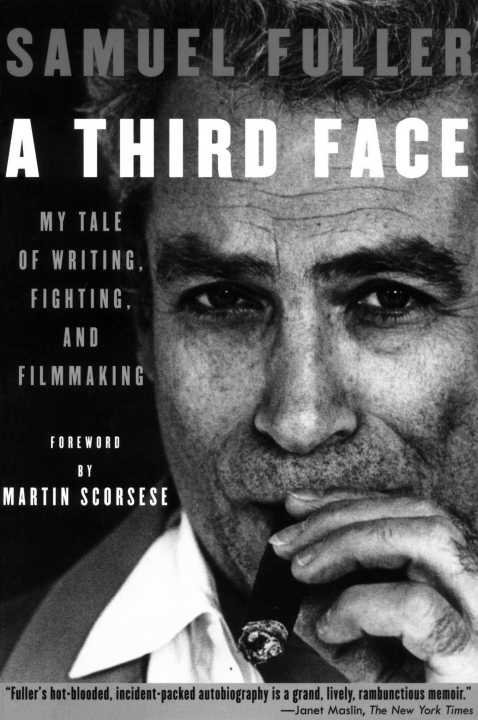

A Third Face

A THIRD FACE

My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking

SAMUEL FULLER

WITH Christa Lang Fuller AND

Jerome Henry Rudes

Contents

xi

PART I

PART 11

PART III

PART IV

PART V

PART VI

Foreword

It's been said that if you don't like the Rolling Stones, then you just don't like rock and roll. By the same token, I think that if you don't like the films of Sam Fuller, then you just don't like cinema. Or at least you don't understand it. Sure, Sain's movies are blunt, pulpy, occasionally crude. But those aren't shortcomings. They're simply reflections of his temperament, his journalistic training, and his sense of urgency. His pictures are a perfect reflection of the man who made them. Every point is underlined, italicized, and boldfaced, not out of crudity but out of passion. And outrageFuller found a lot to be outraged about in this world. For the man who made Forty Guns or Underworld U.S.A. or Pickup on South Street or Park Row, there was no time for mincing words. There's a great deal of sophistication and subtlety in those movies, and it's all at the service of rendering emotion on-screen. When you respond to a Fuller film, what you're responding to is cinema at its essence. Motion as emotion. Fuller's pictures move convulsively, violently. Just like life when it's being lived with genuine passion.

I'll never forget the first time I met Sam. It was in LA in the early '70s, right after a screening of Forty Guns that I'd organized. When the picture was over, we started talking, and we couldn't stop. We talked for hours, but it seemed like a matter of minutes. When it was time to leave, we kept talking as we walked to our cars. When we got there, we were still talking. He would start telling a story, which would lead to another story, which would then lead to a whole other story-a quality that's reflected beautifully in this book by the way. We could have talked all night.

Fuller was one of the rare people who could both "talk" a great movie and make one, too. Many people can do either one or the other, but Sam could do both. I remember once when he and Christa came over to my house for dinner. Sam started talking about an idea that he'd had for a movie about nothing but objects, and drawing the emotion out of the objects. It was absolutely mesmerizing. If anyone could have made such a movie, it was Sam.

The first Sam Fuller movie I ever saw was his first, too. I was six years old, and I'd seen a preview for I Shot Jesse James. I wanted to see it just because of the title. When the day finally came, I remember sitting on the bus with my father on our way to the theater. I was so excited that I couldn't understand how everyone else around us could just go about their business-didn't they realize that I Shot Jesse James was playing? It's a feeling many of us have as children, and we're usually a little let down-the things you look forward to and fantasize about as a kid rarely equal the image you've built up in your head. But this was one time that the movie more than lived up to the image. I ShotJesseJames is a film about betrayal, and it goes right to the heart of it-the way it feels to betray and to be betrayed. I was really struck by the moment when Jesse is taking a bath and Ford aims a gun at his back: Will he shoot, or won't he? I've never forgotten this image, or many others from the movie. I've had them in my head since I was six years old. To this day, the film never fails to move me.

Sam's films had a force that blew all the cliches away from whatever issue they were dealing with. There are no cheap thrills in his work. He was always trying to fathom the unfathomable, whether it was a subject as broad as the inhumanity of war or the injustice of racism, or, on a more intimate level, the thirst for power or the infectiousness of paranoia. In Sam's movies, there's no difference between the personal and the political-both are part of the continuum of human experience. I think he was one of the bravest and most profoundly moral artists the movies have ever had. That's why his war films-The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, China Gate, Merrill's Marauders, and The Big Red One-are the truest, the least sentimental, and the toughest I've ever seen. I only hope that someday, The Big Red One is restored to its original form.

The kid finding his father's body in the alley and vowing vengeance as he makes a fist in Underworld U.S.A. The unbroken tracking shot that follows Gene Evans out into the street as he beats up his opponent in Park Row. The sad, lonely death of Thelma Ritter's stoolie in Pickup on South Street. These are moments of pure, raw emotion, unlike anything else in movies, created by a unique artist. I loved Sam Fuller as a filmmaker, and it's impossible for me to imagine my own work without his influence and example. I came to love him equally as a friend. This wonderful book, filled to the brim with his passion for life and for cinema, goes a long way toward keeping the memory of this precious man alive and well.

Martin Scorsese

Introduction

Sam and I started talking about doing his memoirs together several years before we actually went to work on them. He was reluctant because he felt he still had lots of good yarns in him about other characters. I convinced him that his greatest yarn might be his own life. He didn't like writing a tale with "I" as the central character. But forever young at heart and ready for any new challenge, he quickly adapted to this unique writing mode and relished the job.

Then in 1994, Sam got sick in Paris. We thought we might lose him, but he fought back. The following year, he was well enough to return to our home in Los Angeles. We were already at work on his life story, I typing and he guiding me as best he could. Many of the episodes in Sam's life I had heard recounted over our thirty-three years of living together.

My objective in taking on this challenge was to allow my husband the chance to tell his own version of a long, colorful, and complex life. So much has been written and said about Sam Fuller-the man and the artist-that was biased, exaggerated, simplistic, or just plain untrue. My husband fed the rumor mill, unwittingly or not, with his sometimes incendiary remarks. He was good at being controversial. He loved nothing better than provoking a good debate. "Culture, smulture!" he liked to say, playing down his own profound attachment to scholarship and enlightenment. Proud yet humble, complicated yet primitive, combatant yet peaceloving, Sam was full of contradictions. I am proud to have been the instrument for his own tale, a fascinating story about an admirable, ethical human being.

Our good friend Jerry Rudes has been an invaluable partner in this enterprise, organizing, checking, and editing the manuscript meticulously. Founder of the Avignon Film Festival in France and the Avignon/New York Film Festival in the States, Jerry was very close to Sam. They loved each other like father and son.