Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

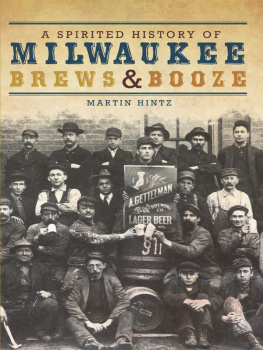

Copyright 2011 by Martin Hintz

All rights reserved

Front cover: Courtesy of Nancy Moore Gettelman.

First published 2011

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.389.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hintz, Martin.

A spirited history of Milwaukee brews and booze / Martin Hintz.

p. cm.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-066-9

1. Brewing industry--Wisconsin--Milwaukee--History. 2. Breweries--Wisconsin--Milwaukee--History. 3. Distilleries--Wisconsin--Milwaukee--History. I. Title.

HD9397.U53M554 2011

338.47663420977595--dc23

2011020343

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

1

The First Pour

Ill have another, please.

Delegate, Moonshiners Convention of Bald Headed Men, Neumuellers Park, June 30, 1889

Historically speaking, the first chapter of Wisconsins brewing and distilling industries in Wisconsin actually began with the French. Etienne Brule is credited with having reached northern Wisconsin in the 1620s during his explorations of Lake Superior, and he probably had a bottle or two of cognac stashed in his canoe. Following Jean Nicolets landing near Green Bay in 1634, French merchants sought beaver skins from the territorys Native Americans, exchanging metal knives, kettles, steel flints, guns and ammunition, woolen blankets and other goods for the valuable pelts. Alcohol, however, was officially prohibited but still easily obtained. All these trade goods were shipped though Mackinac at the head of Lake Michigan and then on to posts in Green Bay, Prairie du Chien and LaPointe.

Over the next generations, most new colonists departed Europe in early March for the six- to eight-week ocean voyage to Canada or New York. From there, the typical immigrant traveled by boat up the St. Lawrence or Hudson Rivers, often through Albany and on to the Erie Canal, across Lake Erie and sailing to Lake Michigan ports such as Milwaukee. Others landed in New Orleans and came up the Mississippi River. The extended journey was enough for a traveler to work up a good thirst. Once settled, the newcomers went to work. For farmers, hops were among the first crops planted in frontier Wisconsin. The hardy vine was common in settler gardens, being used for animal fodder, human consumption, making dye, basket weaving and a multitude of other purposessuch as brewing beer.

James Weaver is credited with being one of the first growers to bring hop roots to the frontier of southern Wisconsin in 1837. He raised the plant on his farm in Sussex, near Milwaukee. A native of Peasmarsh, Sussex County, England, Weaver had lived in New York State, where he grew hops prior to coming to Wisconsin. Also in the spring of 1837, Weavers brother-in-law, David Bonham, opened a small public house, making his own malt beverages in small batches. Since Weavers crops had not yet been harvested, Bonham most likely used English or Eastern hops, which he probably purchased from lake freighters at harbor in Milwaukee.

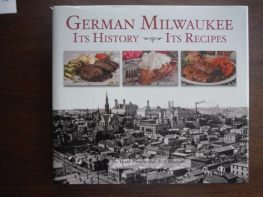

The 1840s saw the advent of the beer business in the burgeoning village of Milwaukee, since it was the beverage of choice preferred by the growing numbers of immigrants. While their Yankee neighbors drank whiskey, the latest arrivalsor at least the Germansgathered in their neighborhood taverns. Theyd sit around the stammtisch, the table of regulars, to drink beer and discuss the latest news. Of course, it helped that the savviest saloonkeepers laid out a goodly supply of free blutwurst (blood sausage), pickled pigs feet, headcheese and slabs of rye bread to go along with the froth.

According to early newspapers, Welsh natives Owens, Pawlett and Davis erected the citys first brewery on the south side of the foot of Huron Street in the spring of 1840. The men opened their Lake Brewery, a small frame building that furnished a sufficient quantity of ale and beer to quench the thirst of all lovers of malt liquor in Eastern Wisconsin. In 1845, the proprietors were obliged to enlarge the premises and during the past year a large brick addition has been built. Richard Owens, Esq., one of the original owners is now sole proprietor, the lesser being Messrs. Powell & Co.

The second brewery in the city was opened in 1841 by German migr Hermann Reuthlisberger (or Reutelshofer), located at the corner of Hanover and Virginia Streets (now South Third and West Virginia) in Walkers Point. Reuthlisbergers brew was popular, but he was underfinanced, soon selling his operations to baker John B. Meyer. In 1844, Meyer unloaded the business to his father-in-law, Francis Neukirch, who carried on the brewery under the Neukirch name. After the Lake Brewery opening, Levi Blossom started his Eagle Brewery, a finely appointed establishment tucked under a hill south of Chestnut Street. About that time, young Phillip Best launched another beer-making operation in the same neighborhood.

In 1849, Wisconsin hosted 22 breweries. By 1856, Milwaukee alone had 20 breweries. In 1859, the number of beer manufacturers across the state had risen to 166. By 1860, nearly 200 breweries operated in Wisconsin, with more than 40 in Milwaukee, although most were quite small. But who cared about size as long as they made beer? Almost every town had a brewery, and some towns formed around breweries. Milwaukee was certainly a place where the phrase roll out the barrel was taken seriously.

2

The Beer Barons

No man should drink too much beer, even if it was good beer, and that forty or fifty glasses a day ought to be the limit for anybody.

Captain Frederick Pabst

Milwaukees entrepreneurial families were closely connected from the citys earliest days. As with medieval fiefdoms in the Old Country, the star players in the communitys upscale world married within their social and economic strata, as did their sons and daughters and, ultimately, many of their grandchildren. Thus did the dynasties thrive and survive. Uihleins were linked with the Pabsts, Brumders, Pfisters, Falks, Vogels, Mitchells, Isleys and others who lived wealthy lives in the New World. Many brewers married the widows of other brewers or the daughter of the boss. Marrying for love was great, but it helped if there was a beer keg in there somewhere, too.

Much like a family, despite intermarriage and even close personal friendships, Milwaukees brewers were often an argumentative bunch. To help resolve issues, they formed the Milwaukee Brewers Association to discuss matters of joint concern, from labor issues to pricing. The barons met regularly at the Second Ward Savings Bank, nicknamed the Brewers Bank, where dues were in relationship to the size of the brewery.

In addition to lobbying against such forces as the growing temperance movement, the loose-knit association also emphasized philanthropy.

Over the years, Milwaukees brewing industry ebbed and flowed due to economy of scale and drinkers tastes. The numbers of breweries declined, mostly due to buyouts and consolidation: from sixteen in 1879 to fourteen in 1890, to twelve in 1910, to eleven in 1935, to six in 1950 and to only three in 1973. Now, the majority of the most fabled corporate names from history are merely produced on a contract basis with another brewery, a conglomerate often not even in Milwaukee.

Next page