Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

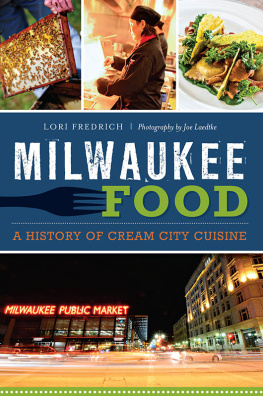

Copyright 2015 by Lori Fredrich

All rights reserved

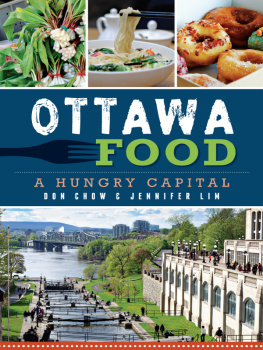

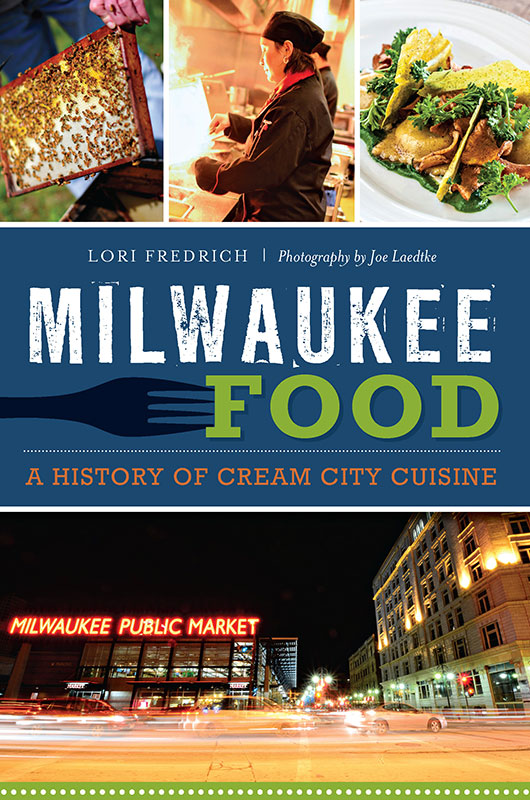

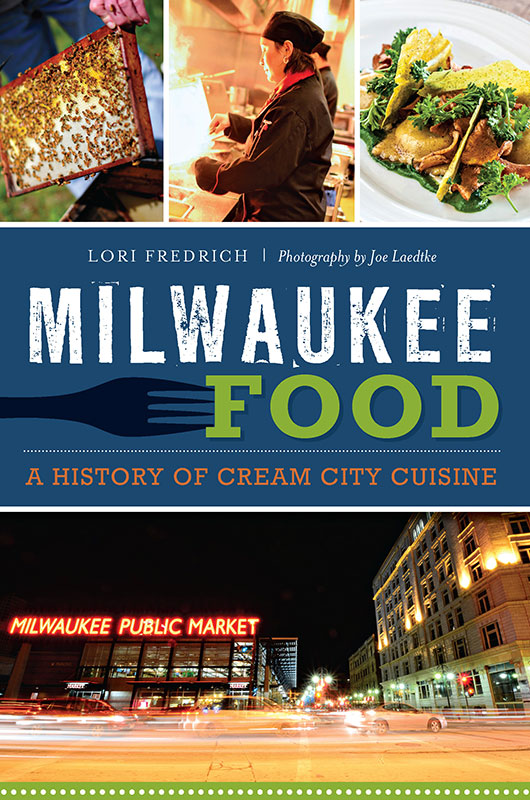

Cover images: Chef Mo of RuYi at Potawatomi Hotel & Casino. Joe Laedtke; produce grown by farms in Milwaukees urban periphery and sold at area farmers markets. Joe Laedtke.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.201.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945703

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.670.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am ever grateful to the many individuals who have supported me as Ive pursued my passions for food and writing. This book is largely dedicated to the chefs, entrepreneurs and food producers who opened their kitchens to me over the years, allowing me a firsthand glimpse into their world.

Thank you to the Marcus Corporationspecifically Jacob Ruck and Cassie Scrimawhose efforts in assisting me to capture elements of the history and imagery of Milwaukees historic hotels were priceless.

I owe a large debt to my husband and muse, Paul, who cooked countless dinners and performed myriad household chores in order to free up my time for writing. He was always there with soothing words of encouragement, and often a glass of bourbon, as I wracked my brain for the strength and courage to finish what sometimes felt like an impossible taskto capture the spirit and passion of a food city on the rise.

To Ellie Martin Cliffe, who swooped in at the last minute to offer her kind services in proofing the manuscript: I am indebted. Im also grateful to Joe Laedtke, whose photographic effortshowever arduousresulted in a work that tells stories not only with words but with pictures. And I would be remiss if I didnt acknowledge the support of Bobby Tanzilo, managing editor at OnMilwaukee.com, for seeing my potential and not only encouraging my hire as a full-time writer but also recommending me as a potential author to The History Press.

I owe my final thanks to the team at The History Press, including production editor Ryan Finn for his keen eye and commissioning editor Ben Gibson, who guided me through the publishing process with deft hands and kindhearted direction.

And lastly, an apology. For many reasons, this work is not exhaustive nor encyclopedic in its scope. A variety of chefs, restaurants and producersall of whom have influenced Milwaukees food culture in significant waysreceive no mention in its pages. As with most works of this nature, there are omissions, and I apologize to anyone who is disappointed not to find their favorite eatery within its pages.

Introduction

This book is a love letter of sorts. Its the story of how a bustling blue-collar towna largely overlooked gem known best for its beer and bratwurstbecame a destination for food lovers. Its also the story of many dedicated peopleproducers, chefs and entrepreneurswho have contributed to the creation of a unique food culture unlike that of any other American city.

For years, Milwaukee crouched beneath the shadow of Chicago, victim of a widespread inferiority complex that focused largely on its deficits while overlooking the significant assets of being a big city with a small-town feel. Bogged down by the loss of its historically industrial roots, the city seemed to lack identity. And a sense of displacement ensued, clouding development and creating a self-depreciating narrative that was largely unfounded.

Many thanks are owed to visionaries like Chef Sanford DAmato and Joe and Paul Bartolotta, who saw a future in the Cream City, laying down their culinary roots and assisting in a sea change for the citys food scene. Additional thanks should be bestowed on the chefs who saw potential in their home city and returned here to add their voices to an ever-deepening culinary conversation, not to mention those who ventured here from abroad and saw the promise of a young scene with infinite opportunity. Without these forerunners, the city would not be what it has become.

Today, although a modicum of the shadow remains, Milwaukee has largely come into its own as a city bursting with cultural outlets, well-groomed parks, a fine zoo, superb natural history and art museums and an endless stream of year-round festivals. And its food sceneproudly devoid of chainshas blossomed into an evolving cornucopia of diverse restaurant options. It is largely driven by chefs whose respect for Wisconsins agricultural bounty and passion for creativity provide the city with wide-ranging options for nourishment and community. It is also a rising star in terms of its contributions to urban food production and farming, an asset to both the environmental health of the city and the food scene itself.

With the exception of Los Angeles and New York City, Milwaukee has opened more successful restaurants per capita during the recent economic downturn than any other city in the nation. That growthpaired with an increasing number of educated, adventurous dinershas created an atmosphere of optimism and excitement in dining that is likely to continue to perpetuate additional growth in the industry.

No longer a city on the fringe of the big leagues, Milwaukee has become a culinary destination worthy of notice. And this is its story.

Beginnings

Before Milwaukee became a dining town, food production was at the fore of its industry. But it wasnt bratwurst and beer that fueled Milwaukees first settlers. It was land.

Prior to the nineteenth century, Native American tribesincluding the Menominee, Fox, Potawatomi and Ho-Chunkwere the sole inhabitants of the Milwaukee area. In fact, the name Milwaukee is derived from the Algonquian word Millioke, which roughly translates to good, beautiful and pleasant land. Of the tribes, the most influential in southeastern Wisconsin was the Potawatomi. However, when French explorers first ventured into the territory in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the native population declined rapidly after succumbing to diseases brought here from Europe.

Jacques Vieau, a French Canadian trader and occupant of Green Bay, is largely considered to be the first resident of Milwaukee. Although he did not live in the area year round, he established a fur trading post from which he dealt with local tribes from 1795 through the 1830s.

The first settlers arrived in Milwaukee in the early 1800s with farming on their minds. They cleared forests and drained swamps, forming three immigrant townsJuneautown, Kilbourntown and Walkers Pointthat would merge in the 1840s to become a unified city. And soon, due to their efforts, wheat became the bumper crop that put the area on the map.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Milwaukee earned the nickname Cream City, a nod to the large number of cream-colored bricks fired in the Menomonee River Valley and used in construction. At its peak, the city produced 15 million bricks per year, with one-third going out of state. But it was the citys ethnic populations that would influence the direction of its development. By 1860, Germans made up the majority, followed by Polish, Irish and eastern European immigrants. The city had more than two dozen breweries dotting the city, sponsoring beer gardens throughout.

Next page