All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777, info@accesscopyright.ca.

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC, V0N 2H0

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

We are a living people and a living culture. I believe we are bound to move forward, to experiment with new things and develop new modes of expression as all peoples do.

Daphne Odjig, Potawatomi, artist

There are images, songs and words that will appear

at your death like familiar birds to accompany you

on your journey to the sky.

From sudden awareness by Joy Harjo, Muscogee Creek,

poet and musician

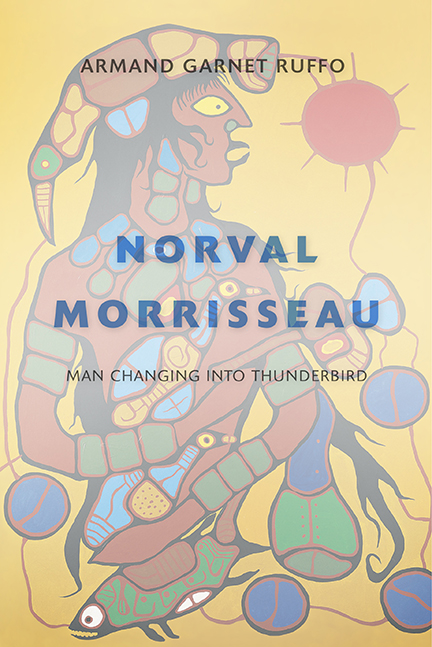

Introduction

What began it all was Norval Morrisseau rising like his spirit name Copper Thunderbird from the alleys of Vancouvers east end and, again, making headlines. He would become the first Indigenous painter to have a solo show at the National Gallery of Canada. The year was 2005 and Greg Hill, curator and head of Indigenous art for the National Gallery, was organizing the Norval Morrisseau, Shaman Artist retrospective. Knowing that I am of Ojibway heritage, he asked me if I would write something about the acclaimed Ojibway painter for the accompanying catalogue. I told him that I would have to think about it. Because of Morrisseaus incredible reputation, I knew something about himsince his breakthrough solo show in 1962 he had more or less always been in the newsbut frankly not very much. Although I was from northern Ontario, I never actually saw his work until I moved to Ottawa to work for the now-defunct Native Perspective Magazine in the late 1970s . I would later learn that in the early seventies he had participated in an educational tour of northern Ontario schools, but for some reason the art circuit had bypassed mine. It wasnt until 1982 that I attended an exhibition of his at the Robertson Galleries in Ottawa.

I did think about it, and I waited. Waited for something to tell me either to take on the project or let it go. What did happen, then, was a combination of dreaming and remembering. I was in bed for the night, the dark room lit only by the streetlight sliding under the drapes. I thought I heard something. I sat up and listened attentively. Footsteps. Voices. I stilled my breath and waited for a moment that seemed unending. Then a lone car passed below on the street, splashing along the wet pavement. I fell back asleep. The next morning I thought about what I had heard, or thought I heard. The voices, I realized, had come from the old flat-roof house of my childhood in the north. Perhaps from my mother and the neighbours who had dropped by for a visit, a chat, a drink. There had been lots of drinking in those days and nights. I still held the image of us kids tearing off downtown with a few coins rattling in our pockets because my mother and her friends were partying and wanted to get rid of us. Fortunately for me it didnt happen very often, but it did happen and I remember it well.

The more I thought about Morrisseau and his life, the more I realized that his experiences, while extraordinary in their own right because of his unique gifts, were fundamentally connected to something larger than himself. I realized that Morrisseaus life was representative of the profound upheaval that had taken place in the lives of Native people across the country. With their traditional economies and support systems in ruins, they were thrown into abject poverty, families literally starving to death, and it was into this milieu that Morrisseau, like my mother, was born in 1932 (which is the birth year he acknowledged in a Department of Indian Affairs cultural development application). A period that coincided with the unparalleled movement by Native peoples to cities and one-industry towns across the country to find workshell-shocked as they were by a history of missionaries, decades of residential schooling that taught them to hate everything Indian, hate even themselves, the overt racism that made them stand at the back of the line, the total disregard and denigration of their cultures, the stereotypes that continually projected Hollywood versions of them whooping and hollering on the screen. And whoop and holler they did as many of them sought relief in forgetting. Or, on the contrary, in remembering what they could of the old ways, sought out their own kind, their community, and with what little money they had, drowned their sorrows.

The main difference of course in Morrisseaus case was his immense talent. Nevertheless, I realized that like an intricate spiders web his life was very much part and parcel of what I might call the great upheaval. The details of his life, his aesthetics, his technical achievements, his idiosyncrasies, all of it hearkened back to who he was as an Indian at a particular time and place in colonial Canada.

I called back a couple of days later confirming that I would write the piece, but with a few conditions. I did not want to write the standard academic essay that the National Gallery of Canada might expect. And I made it clear that I was not interested in reportage. What I wanted to do was tell a story. I wanted to employ the traditional form of acquiring knowledge that is central to Ojibway culture and to Native cultures in general. And, as much as possible, I wanted to ground my story in Anishinaabe epistemology and what we now call oral history. That would mean I would have to talk to people and learn a great many things, but then wasnt that the point? Another thing: I would write a couple of pieces and then fly out to Nanaimo and present them to Morrisseau himself. If he agreed to my approach, I would go ahead with the project.

When I finally met Norval Morrisseau I have to admit that I was intimidated by his imposing presence, even as he sat in his motorized wheelchair. Numerous journalists have spoken about it, and Ill confirm here that its true. There was something about him that only a rare few possess. Whatever it iscall it charisma, powerMorrisseau had buckets of it, and it undoubtedly was part of the reason he was able to attract a large and continuous entourage throughout his life. I had been led into a sunlit room by his caregiver and adopted son Gabe Vadas and found myself standing awkwardly in front of the artist, glancing nervously at the spectacular paintings on the walls, while Vadas kneeled before him and spoke quietly about me. Then Vadas stood back and with a nod indicated that I should give him the book of poetry that I had brought for the occasion. Looking up at me, emotionless, Morrisseau slowly raised his trembling hands and accepted the book.