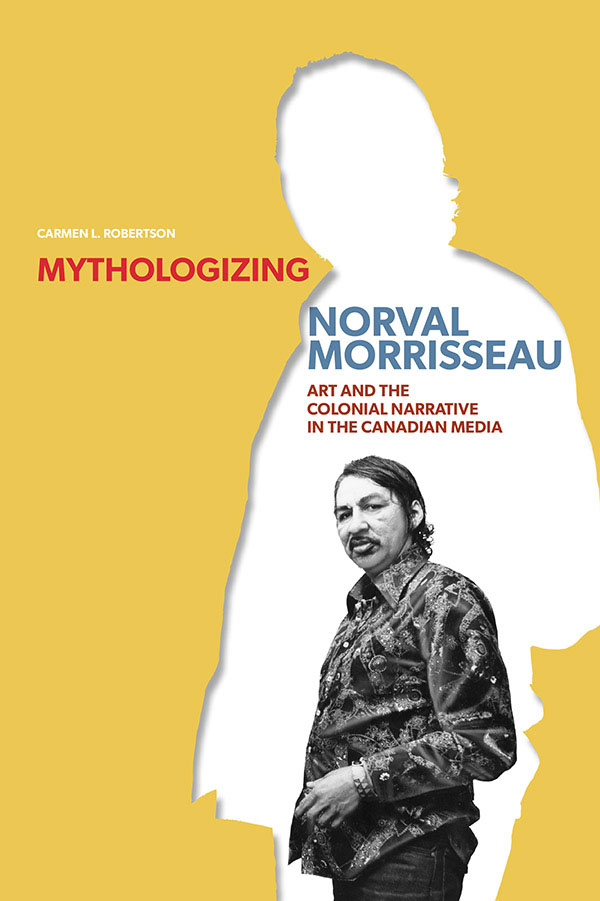

MYTHOLOGIZING

NORVAL MORRISSEAU

ART AND THE

COLONIAL NARRATIVE

IN THE CANADIAN MEDIA

CARMEN L. ROBERTSON

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Canada R3T 2M5

uofmpress.ca

Carmen L. Robertson 2016

Printed in Canada

20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca, or call 1-800-893-5777.

Cover design: Kirk Warren

Interior design: Karen Armstrong Graphic Design

Cover photo: Dick Loek/GetStock.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Robertson, Carmen L., 1962, author Mythologizing Norval Morrisseau : art and the colonial narrative in the Canadian media / Carmen L. Robertson.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-88755-810-8 (pbk).

ISBN 978-0-88755-501-5 (pdf ).

ISBN 978-0-88755-499-5 (epub)

1. Morrisseau, Norval, 1931-2007Public opinion. 2. Morrisseau, Norval, 1931-2007In mass media. 3. Morrisseau, Norval, 1931-2007Appreciation. 4. Native artistsCanada--Public opinion. 5. Native artistsPress coverageCanada. 6. Native artPress coverageCanada. 7. Native peoplesPress coverageCanada. I. Title.

ND249.M66R6 2016 759.11 C2015-907999-3

C2015-908000-2

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Discipline, Performativity, and Morrisseau

Native artists had to know how to play the white mans game, they had to be able to work the media and the market, or they werent going anywhere.

Sarah Milroy, Globe and Mail, 7 February 2006

With the 2006 opening of Norval Morrisseau: Shaman Artist at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, two of Canadas leading newspapers, the Globe and Mail and the Ottawa Citizen, characterized the Anishinaabe artists retrospective as a taming of demons. first, artist second.

In a recent essay for the National Museum of the American Indians exhibition Before and After the Horizon: Anishinaabe Artists of the Great Lakes, curator Gerald McMaster acknowledges that Norval Morrisseaus rise in the early 1960s gave significant voice to later generations of First Nations artists across the country. McMaster describes how Morrisseau quickly became an iconic, tragicomic artista role frequently reinforced by the art worldand, to his credit, he was often more than happy to oblige. At the same time, his character and strategies were quite different because, while he may have been characterized as a primitive, he was also extremely serious about the decrepit conditions in which most Aboriginal peoples lived. McMasters analysis of Morrisseau is based on forty years of study and analysis, and he clearly identifies the artists deep understanding of Canadian colonial culture. I disagree with McMaster, however, when he says that the art world not only accepted difference but encouraged it. The media, and newspaper art critics in particular, did not, for the most part, approve of Morrisseaus difference. While titillated by his exoticism, the press largely disparaged his difference, scorned his performative gestures, and often positioned his art as primitive. Much finger wagging followed the artist, who was mostly interested in painting his unique visual stories and pushing boundariesboundaries that shifted because of the artists trailblazing efforts.

As Canadas first Indigenous art star, Morrisseau served as a test case of sorts for the media to teach readers about artistic expressions of identity and difference. His racialized identity remained key to this lesson. The educative role of media in relation to race is a relatively understudied topic yet clearly, as described in the literature, the media does more than simply report the news. Political scientist Paul Kellstedt argues that although understandings of how the press has covered race are largely ignored by scholars, the presss influence in matters of race is a form of social learning.

This study is not simply about the role of the media in constructing a racialized identity for the artist. It also investigates Morrisseaus own performative gestures in questioning and resisting the confining box of stereotypical tropes into which the press so easily plunked him. Often, media narratives and Morrisseaus own commentary stood at odds. At times Morrisseau confronted the press, challenging reporters to cover his artistic achievements rather than focus on his personal life. Yet Morrisseau also manipulated his shaman persona, spoon-feeding the media a construction not so different from what they craved.

The mythology surrounding Morrisseau is not easily unpacked. Fraught with identity politics, colonial misconceptions, racialized tropes, and Morrisseaus own implicated ways of framing himself, intertwined signifiers cross-pollinate in complex ways. Meaning is always in process and as a result is unstable because readers bring multiple meanings to texts. My reading of the texts and images in this study is a product of my positioning as an Indigenous female, as an academic, and as someone who grew up in rural Saskatchewan in the 1960s and 1970s constituted, constrained, and enabled in a criss-crossing of discourses. Drawing on press coverage, Morrisseaus engagement with media sources, and a variety of other sources, I have gathered together a narrative that considers not only the man and his art, but also Canadas role in forging the story of Morrisseau.

In this way, Morrisseau can be understood as a discourse, a myth, a fantasy; part of a larger colonial narrative that helps explain the Canadian nation. Roland Barthes explained myth as a particular type of discourse: Myth is depoliticized speech ... [It] does not deny things, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification. No one domain deserves explanatory value over another. Utilizing a wide range of media sources and other texts, I hope to illuminate the complex interaction of discourses, made legible in particular moments that maintain the mythology surrounding this artist.

In a process of naturalization, Canada has sought to erase its colonial past. At a G20 summit news conference in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, in 2009, Prime Minister Stephen Harper naively stated, We have no history of colonialism. With Morrisseau as an object of study, a nexus of colonialism, the gaze, and the politics of performance emerges that is not a simple thing, but which draws attention to the complications of such an examination. Gathering the strands of this analysis does not lead to a single, monolithic interpretation but rather highlights the many ways in which Canada tries to absolve itself from complicity with its colonial past and present.