Contents

Guide

First published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

John Ambrose Hide, 2019

The right of John Ambrose Hide to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Black Plaque and Black Plaques are a registered trade mark of John Ambrose Hide.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9117 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

T his collection of stories from the past makes use of the vocabulary and social graces of former days that is to say, the physically sick called for a physician and the mentally sick a lunatic asylum or madhouse, while voyeurs patronised freak shows, felons were sent to gaol, the thirsty headed to an alehouse (and subsequently a boghouse), and the lecherous sought not a sex worker but a bawd, harlot, whore or strumpet.

On a similar cautionary note, it is hoped that the expressed premise of bringing to light a mixed buffet of succulent historical exploits will appeal to a particular class of inquisitive gourmand, however courtesy obliges mention that thanks to the lavish detail provided in the depictions, there may exude from this book a tang more gamey than to some readers tastes.

Dates are given in modern style and both the spelling and punctuation of quoted material are modernised if it helps clarity.

The photograph of a detail from Jean Cocteaus mural in the Church of Notre Dame de France is used with the kind permission of the church as well as the Comit Jean Cocteau.

INTRODUCTION

T he Black Plaques portrayed in this book are not to be found proudly mounted on a wall, and as will swiftly become clear, for good reason. What with their commemoration of a brutal execution outside Westminster Abbey, the selling of sex toys in St Jamess Park, and an intruder at Buckingham Palace with Royal undergarments stuffed down his crotch, this is not the sort of subject matter that authorities choose to grace a buildings facade or depict on a visitor information board. In fact, many people might hope that such indecorous and inconvenient episodes remain quietly overlooked.

But Black Plaques jog such artful lapses of memory. At a stroke, Londons familiar streets and buildings are cast in a quite different light when imprinted of necessity by proxy, with these Memorials to Misadventure, thus drawing long overdue attention to awkward moments history has done its utmost to discreetly ignore, misrepresent, or prompt a timely bout of amnesia happily, circumstances that offer fertile conditions for stories of exquisite ripeness.

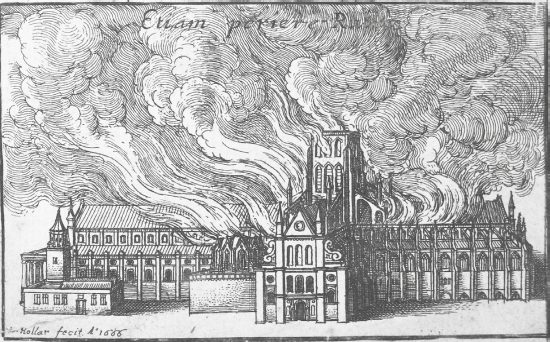

My motivation to lavish Black Plaques on London arose after a visit to that icon of the city, St Pauls Cathedral, for it was only sometime after a visit, I happened to discover that in 1514 a man imprisoned at the buildings medieval precursor was murdered by virtue of a red hot needle thrust up his nose. And not only that; the perpetrators of this impolite enterprise were churchmen who endeavoured to bestow the bloody scene with the semblance of suicide for which the corpse then stood trial in the Lady Chapel. Such a startling sequence of events is not considered worthy of even a footnote in the official history of the Cathedral a weighty tome with the proportions of a paving slab so needless to say, neither does it feature anywhere in todays visitor experience. My discovery left me with the feeling that I had been denied the opportunity to stand where events took place and quietly contemplate the mother of all nosebleeds.

While this inglorious affair came as news to me, it is by no means unknown to scholars of the Tudor period, however their focus is not unexpectedly directed towards learned interpretations of the episodes context and consequences, as opposed to the nitty-gritty of its unpleasant operation at what is now a global tourist attraction. Similarly, the Cathedrals governing body concerns itself with priorities far loftier than acquainting visitors with earthy tales of brain-skewering on the premises, yet this was a tale needing to be told about St Pauls and a commemorative plaque inevitably one both unofficial and incorporeal was the means to correct this oversight.

When it came to delving into the dustbins at other locations, it soon became apparent that this was not an isolated instance in which the powers that be had covered a compromising stain with carefully placed rug. And so as a matter of public duty I began to bestow Black Plaques each one a vignette of an unbecoming event at a particular locale, where the blot in question is at best obscured, at worst obliterated from common consciousness, and its uncomfortable truths are distilled into a compendious inscription. Thus, Black Plaques London offers an antidote to run-of-the-mill guidebook spiel on sites such as Covent Garden, Regent Street or Banqueting House, and besmirches the reputation of umpteen less prominent addresses. At many of the sites there are no physical remains that relate to the dishonourable deeds depicted as is the case with the prison at the old St Pauls which of course has helped those unsavoury blotches to fade into obscurity.

The Great Fire of 1666 expunges reminders of an awkward episode at St Pauls.

While perched on the threshold, this is an opportune moment to mention that among the words of remembrance offered herein, nostrils are by no means the only bodily orifice to be poked with something. Eligibility criteria for Black Plaques place no subject off-limits and some of the dedicatory epigraphs are richly laden with lewd and lurid details that are perhaps not everyones cup of tea; even this introduction is soon to make an insightful deviation into what London Undergrounds indefatigable cleaners refer to as Code Two.

For those still reading, so as not to cause misunderstanding I should also give forewarning that Black Plaques are not simply a generous slice of forbidden fruit. Granted, they shine a spotlight on womens breasts offered up to the caresses of a dead mans hand, and boys buttocks yielding to the vigorous attentions of the Bishop of London, but moments of indelicacy such as these are counterbalanced by altogether more sober and sobering sagas. I explain this uneasy mixed bill of levity and gravity shortly, but beforehand it is instructive, and I hope not too wearying, to engineer an encounter between conventional (and in London, most commonly blue) plaques and their troublesome new in-laws.

Should a visitor from outer space assess the track record of our species solely by reading commemorative plaques, it is not controversial to conclude that they would form a thoroughly undeserved impression of Earths self-ordained wise hominids. But labouring under this inordinately generous view, our interplanetary guest might query why these unpredictable blue blobs tend to mark merely the house (or site of the house) in which our exemplary specimens lived. Such a discerning extraterrestrial and I cannot be alone in wondering what links the four walls that enclosed our paragon of virtues domestic, sleeping and ablutionary arrangements with their praiseworthy endeavours. Furthermore, humankind exhibits the inconvenient habit of moving house, so the notably peripatetic Charles Dickens has bagged eight plaques in London solely for places in which he lived (or even stayed). Dickens reputation justifies such a number but perhaps the seventeenth-century Master Astrologer William Lilly ought to have foreseen that were he more domestically mobile, he might be better remembered. (Lilly is commemorated with a sole plaque mounted on the disused Strand/Aldwych Underground station a place I fancy he would not have been familiar with.) Plaques such as these do not explicitly identify where something of significance took place; they are not pinpointing what you might call hallowed ground.