The Lives and Homes

of Londons Most

Interesting Inhabitants

Edited by HOWARD SPENCER

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in 2016 by September Publishing

Copyright English Heritage 2016

The right of English Heritage to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder

Publisher: Hannah MacDonald

Project editor: Charlotte Cole

Design: Two Associates, Martin Brown

Picture research: Abigail Lelliott

Maps: Mark Fenton, Clifford Manlow

Proofreader: Beth Hamer

Indexer: Stephen Blake

Production: Rebecca Gee

Printed in China on paper from responsibly managed, sustainable sources by Everbest Printing Co Ltd

ISBN 978-1-910463-39-0

ePUB ISBN 978-1-910463-40-6

September Publishing

www.septemberpublishing.org

English Heritage is a charitable trust; as well as running the capitals plaque scheme, it looks after over 400 ancient monuments across England including Stonehenge, Hadrians Wall, Dover Castle and Tintagel. The blue plaques scheme is now entirely reliant on donations. Please consider making a donation through our website.

www.english-heritage.org.uk

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

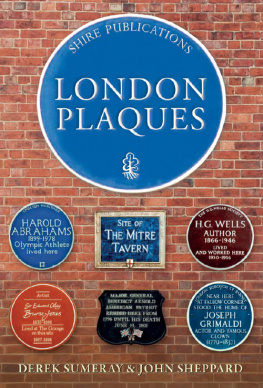

T HE plaque is the most common form of public commemoration today, replacing the tombs and statues which fulfilled that role in previous centuries. It is the perfect one for a democratic age, in that all of the people honoured with one, irrespective of their social status, occupation or the decade in which they died, have their names and reason for fame inscribed upon an object of identical design. They thus take their places in an open-air pantheon, growing as the decades pass. Furthermore, they are intrinsically connected with a building of special significance to the life and work of the individual concerned, and some of that persons distinction is shared by the structure in which they resided or worked. As metal, in the form of a crown, confers a mystique when placed upon a humans head, so a piece of ceramic, called a plaque, can do the same to the building on which it is set. It brings together person, place and story in a way done in legends since human time began, but in a specially tangible and objective form. As well as informing passers-by and honouring the dead, it can also play a role in giving further appreciation to a solid structure.

The Blue Plaques scheme of London is the oldest in the United Kingdom. It belongs to the people, in that anyone is free to propose somebody for commemoration on a plaque; but the worthiness of the subject is determined by the panel that I chair, against very high standards of enduring fame. That panel is composed of experts in the British record of every branch of human activity, all bearing national and/ or academic honours, and serving for fixed periods to ensure freshness of approach. They are provided with further detailed information on each candidate, requiring intensive research currently undertaken or overseen by the schemes resident historian, Howard Spencer. This book is infused with his unmatched knowledge, his profound love of the people and places concerned, and his eye for a sharp one-liner. My own sense of what London is, and what it is to be a Londoner, and has been, is immeasurably enriched by it.

Like the scheme of which it is a distillation, this book keeps faith with past, present and future. It keeps faith with the past, by recognising the Londoners whose lives and work have been of especial benefit to their fellow humanity, and who have made a lasting impact on history. It keeps faith with the present, because the choice of recipients for plaques involves a recognition of what the contemporary world values and thinks worthy of memory and of applause. It also keeps faith with the future, by holding up to it an image of what modern Britain has believed to constitute greatness. Those robust and beautiful ceramic circles set into a wall, not screwed to it will last as long as the buildings themselves. In a thousand years from now perhaps a visitor from Australia or even Mars will survey the ruins of London, see and read these plaques, and know from them what we were worth as a civilisation.

Professor Ronald Hutton

English Heritage trustee and Chair of the English Heritage Blue Plaques Panel

INTRODUCTION

B LUE plaques are as much a part of the London street-scape as red telephone boxes, plane trees and terraces of stucco and stock brick. Their laconic inscriptions, telling of where famous figures of the past were born, lived, worked and died, have been informing, educating and entertaining passers-by for 150 years.

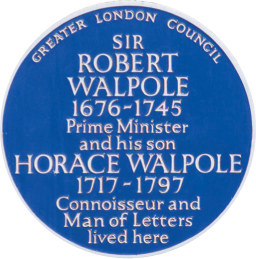

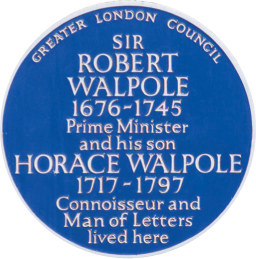

Lord Byron had the honour of being the recipient of the very first official London plaque, in 1867. The scheme was started by the Society of Arts (now the RSA) the year before, after a suggestion by the MP William Ewart.* In 1901 the plaques scheme was taken on by the London County Council (LCC), and a senior administrator at the council, Laurence Gomme,* was largely responsible for shaping the plaques scheme into a form we would recognise today.

From 1965 the Greater London Council (GLC) took blue plaques into a wider geographical area, reflecting the suburban spread of the capital. Somewhat confusingly, the London blue plaques scheme does not cover the square mile of the City, where the Corporation of London operates its own scheme. (The plaque to Dr Johnson in Gough Square is the single exception to this rule.)

In 1986 the GLC was abolished and the scheme passed to English Heritage, then a government agency, and which became a charitable trust in 2015.

The blue plaque has become, to employ an over-used term, a design icon and has been much imitated and parodied. The plaques now used in London are 19in (495mm) round, but can be smaller if this better suits a particular building. Made of ceramic slipware, the plaques are inset into walls to a depth of about 2in (50mm). They are the work of skilled craft ceramicists, most recently the Ashworth family. Slightly domed so as to be self-cleaning, they are intended to last for as long as the buildings they adorn.

The design history, however, is complicated. Not all blue plaques are blue, for a start; many of the earlier tablets to use the term once favoured were terracotta or brown. Green and grey ceramic has also been used, as have other materials, including bronze, lead, stone and enamelled steel. And just to add to the fun, plaques are not all round either: squares, rectangles and other shapes also feature.

Official plaques almost invariably feature the name of the responsible body in their inscription. The Society of Arts embedded its name discreetly in an intricate border, while the former London Councils put their monikers on more prominent display. The same goes for English Heritage, which added its famous portcullis logo. The exceptions are a handful of plaques that were put up privately and later officially adopted. Some good examples of these may be found in Bloomsbury, where ornate bronze plaques complete with cherubs were put up by the landowner, the Bedford Estate.

Next page