I would like to thank the following friends and family members who, over the years, helped me to complete the three editions of this book by showing me quotes and anecdotes about Blue Plaque subjects or by pointing me in the direction of useful books: my late father, Philip Rennison, my mother Eileen Rennison, Hugh Pemberton, Susan Osborne, Andy Taylor, Andrew Holgate, Gordon Kerr, Richard Shephard, Paul Skinner, Andy Walker and Eve Gorton. While I was compiling the first edition of the guide in the late 1990s, Gillian Dawson of Westminster City Council, Geoff Noble of English Heritage and Ruth Barriskill of the Guildhall Library all helped to make my job easier. The first two editions of the book both benefited from the editorial input of Rupert Harding and Clare Bishop of Sutton Publishing. The third edition, published by The History Press, could not have been produced without Jo de Vries, Editorial Director, whose interest in the project and enthusiasm for it encouraged me to update a book which I first wrote more than a decade ago. This fourth edition owes much to the hard work and encouragement of Sophie Bradshaw and Naomi Reynolds at The History Press.

The author and publisher are grateful for permission to reproduce pictures:

from the English Heritage Photographic Library: pp.

from Illustrated London News : pp.

by courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London: pp.

CONTENTS

The idea of placing commemorative plaques on the houses of the great and the good was first mooted in 1863 by William Ewart. Ewart was a Liberal MP whose most significant achievement was the passing of the Public Libraries Act of 1850, which he had introduced as a private members bill the previous year. In putting forward the idea of commemorative plaques he wrote that the places which had been the residences of the ornaments of their history could not but be precious to all thinking Englishmen. (Ewart himself now has his own Blue Plaque in Eaton Place, erected 100 years after he first proposed the idea.) Sir Henry Cole, the first director of what we now know as the Victoria and Albert Museum, was one of those who most vigorously championed Ewarts proposal. Ewarts original intention had been that the government would fund a plaque scheme, but the administration of the day declined to do so. The Royal Society of Arts (RSA) stepped into the breach and in 1864 formed a committee to oversee the choosing and erection of the first plaques. The committee was enthusiastic about the idea that the plaques might give pleasure to travellers up and down in omnibuses etc, and that they might sometimes prove an agreeable and instructive mode of beguiling a somewhat dull and not very rapid progress through the streets but, as committees do, it took time to turn its words into actions. It was not until 1867 that the first plaque was erected under the auspices of the RSA. This was placed on 24 Holles Street, once the home of Lord Byron and now, sadly, demolished.

The erection of plaques under the RSA was a slow and stately process. By 1901, when the scheme was taken over by the London County Council (LCC), thirty-six plaques had been put up in thirty-four years. Many of these have now disappeared, the victims of development, demolition and wartime bombs. The oldest plaques still in place are those to Napoleon III in King Street and to the poet John Dryden in Gerrard Street both date from 1875. Under the LCC the speed with which plaques were erected quickened significantly; they were in charge of the scheme for sixty-four years and put up more than 250 plaques in that period. When, in 1965, the LCC metamorphosed into the Greater London Council (GLC), the new organisation took responsibility for the plaques. Under the GLC the geographical and cultural range of the plaques both expanded. Plaques were erected in outlying London boroughs that had not been under the jurisdiction of the LCC, and there was a more populist choice of individuals deemed worthy of commemoration. (Somebody at the GLC seemed to have a particular fondness for old music-hall stars. At least half a dozen were given their own plaques in the GLC years.) In 1985, with the abolition of the GLC, a new home had to be found for the Blue Plaque scheme (as it was now popularly known) and the Local Government Act of that year gave responsibility to English Heritage.

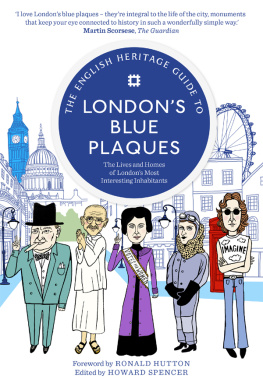

For thirty years English Heritage have continued to run the scheme and they have put up a further 360 plaques. Currently the decisions about which people should and should not be commemorated are made by the Blue Plaques Panel, which meets three times a year under the chairmanship of Professor Ronald Hutton. Other members of the panel include Sir Peter Bazalgette, Greg Dyke, Professor Jane Glover and the former Poet Laureate Sir Andrew Motion. In 2012, there were a number of newspaper reports, most of them inaccurate, suggesting that the scheme was being suspended because of funding cuts. In fact, as English Heritage hurried to make clear in a statement, the scheme was only temporarily closed to new applications while a backlog was reduced. In June 2014, thanks in particular to a generous donation by one individual, the scheme reopened to nominations.

What criteria are used to select the recipients of a Blue Plaque? Any scheme which, in the same year (2014), can commemorate the crime novelist Raymond Chandler, the nineteenth-century Irish political leader Daniel OConnell and the comedian Tony Hancock, obviously has pleasingly wide-ranging terms of reference. When the official scheme began under the RSA, there were few hard and fast guidelines but, under the LCC and the GLC, rules developed and English Heritage now publish a set of principles for the choosing of those honoured by Blue Plaques. These people must be regarded as eminent and distinguished by a majority of members of their own profession or calling. They must have made some important positive contribution to human welfare or happiness. They must be of significant public standing in a London-wide, national or international context and their achievements should have made an exceptional impact in terms of public recognition. Perhaps the last condition is sometimes honoured in the breach rather than the observance. How much public recognition is there of the name of Sir Fabian Ware, the founder of the Imperial War Graves Commission? Or Dame Ida Mann, a leading twentieth-century ophthalmologist? Or the Victorian sculptor Carlo Marochetti? Yet all three have been honoured in the last few years and who would begrudge them their plaques? Part of the delight in coming across London plaques is the stimulus it often gives to discovering more about the Citys past inhabitants. The principle of selection on which English Heritage has been most insistent is the one of time. Without exception, people will not be considered until they have been dead for twenty years. Inside these guidelines, and a few others, English Heritage works hard to come up with new people to commemorate; at present, between ten and fifteen new plaques are unveiled each year. English Heritage has also shown itself eager to democratise the process of choice. If you know of a building and individual that you believe worthy of a plaque, you are free to contact English Heritage with the suggestion. A nomination form can be downloaded from their website.

The success of the official London Blue Plaque scheme means that it has been widely copied both in the capital and in other parts of the country. Between 1998 and 2005, English Heritage itself sponsored an expansion of the Blue Plaque scheme into other English cities. Liverpool had English Heritage plaques installed to more than a dozen of its famous residents, including the poet Wilfred Owen, The Beatles John Lennon (also recently honoured with a London plaque) and the toy manufacturer Frank Hornby. At the end of 2002 the first English Heritage plaques in Birmingham were erected on houses where the brothers Cadbury, chocolate manufacturers and philanthropists, once lived and they were followed by five more. Plaques were also installed in Southampton (R.J. Mitchell, designer of the Spitfire aircraft, Emily Davies, the campaigner for womens education and four others) and Portsmouth (the comic actor Peter Sellers, the historian Frances Yates and five others). However, these schemes were only ever intended as pilots and, for a number of reasons, running them in cities outside London proved unworkable. They were stopped in 2007.

Next page