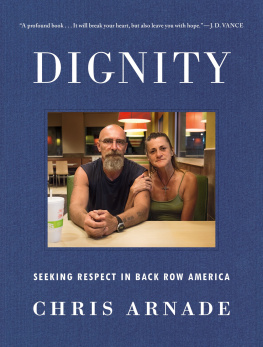

When interviewing people for this book, I took notes on paper but did not record the conversations. How exact the notes were depended on the situation. On the streets, I jotted down what I could on the spot and filled in the rest later, usually just moments after while my memory was fresh. Inside churches or McDonalds or peoples homes, I was able to take more extensive immediate notes.

I tried to record as accurately as possible each persons words, and if they said something particularly important, I asked them to repeat it to make sure I got the exact phrasing. At the end of each day I typed my notes into my computer, expanding on them and recording my own observations.

Conversations re-created here in the book are quoted as exactly as possible, though they may not be verbatim, since I edited them for clarity.

Due to the sensitive nature of many of the conversations or the precariousness of interviewees circumstances, I have changed the names and identifying details of some of the people I interviewed. For those in Hunts Point about whom Ive already written, I use the street names I used in those pieces.

When those I interviewed requested assistance, I did my best to provide it. Usually this meant buying them a meal at McDonalds, a few cigarettes, or a sandwich at the deli. If they asked instead for outright cash, I either declined or gave them five or ten dollars. In extreme cases, I offered to bring someone to detox or rehab. My rule was to help people I was writing about the same way I would have helped them had I not been writing about them.

The people in this book deserve more than a meal at McDonalds or a fiver or an hour using my computer, though. I am donating part of my proceeds from this book to groups working with addiction and homelessness, as well as setting aside money, to be administered by a third party, to help with housing, food, or medicine for those featured in the book and those I met during my trips.

Introduction

I first walked into the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx because I was told not to. I was told it was too dangerous, too poor, and that I was too white. I was told nobody goes there for anything other than drugs and prostitutes. The people directly telling me this were my colleagues (other bankers), my neighbors (other wealthy Brooklynites), and my friends (other academics). All, like me, successful, well-educated people who had opinions on the Bronx but had never really been there.

It was 2011, and I was in my eighteenth year as a Wall Street bond trader. My workdays were spent sitting behind a wall of computers, gambling on flashing numbers, in a downtown Manhattan trading floor filled with hundreds of others doing exactly the same thing. My home life was spent in a large Brooklyn apartment, in a neighborhood filled with other successful people.

I wasnt in the mood for listening to anyone, especially other bankers, other academics, and the educated experts who were my neighbors. I hadnt been for a few years. In 2008, the financial crisis had consumed the country and my life, sending the company I worked for, Citibank, into a spiral stopped only by a government bailout. I had just seen where ourmy own includedhubris had taken us and what it had cost the country. Not that it had actually cost us bankers, or my neighbors, much of anything.

I had always taken long walks, sometimes as long as fifteen miles, to explore and reduce stress, but now the walks began to evolve. Rather than walk with some plan to walk the entire length of Broadway, or along the length of a subway line, I started walking the less seen parts of New York City, the parts people claimed were unsafe or uninteresting, walking with no goal other than eventually getting home. Along the walk I talked to whoever talked to me, and I let their suggestions, not my instincts and maps, navigate me. I also used my camera to take portraits of those I met, and I became more and more drawn to the stories people inevitably wanted to share about their life.

The walks, the portraits, the stories I heard, the places they took me, became a process of learning in a different kind of way. Not from textbooks, or statistics, or spreadsheets, or PowerPoint presentations, or classrooms, or speeches, or documentariesbut from people.

What I started seeing, and learning, was just how cloistered and privileged my world was and how narrow and selfish I was. Not just in how I lived but in what and how I thought.

This was a slow and shocking revelation to me, one I kept trying to fight. I certainly already knew I was privileged. I had a PhD in theoretical physics. I worked as a bond trader at a big Wall Street firm. I lived in the best part of Brooklyn. I sent my kids to private school. But like most successful and well-educated people, especially those in NYC, I considered myself open-minded, considered, and reflective about my privilege. I read three papers daily, I watched documentaries on our social problems, and I voted for and supported policies that I felt recognized and addressed my privilege. I gave money and time to charities that focused on poverty and injustice. I understood I was selfish, but I rationalized. Arent we all selfish? Besides, I am far less selfish than others, look at how I vote (progressive), what I believe in (equality), and who my colleagues are (people of all races from all places).

I also considered myself to be different from those immediately around me. I hadnt grown up wealthy. I had grown up in a tiny working-class southern town. Sure, my father was a professor of international relations, my mother a librarian, but we didnt have much money, certainly not by the standards of the NYC I was now part of. I hadnt gone to boarding schools, or private high schools, and then to Harvard or Yale. I went to the local public high school, and then to the state college, paid for by money I had made working jobs since I was thirteen. Of course, I had ended up getting a PhD in theoretical physics from Johns Hopkins. But, I told myself, that is physicsit is rational and erudite. That is different. It isnt Harvard Business School.