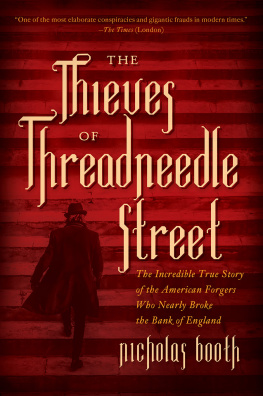

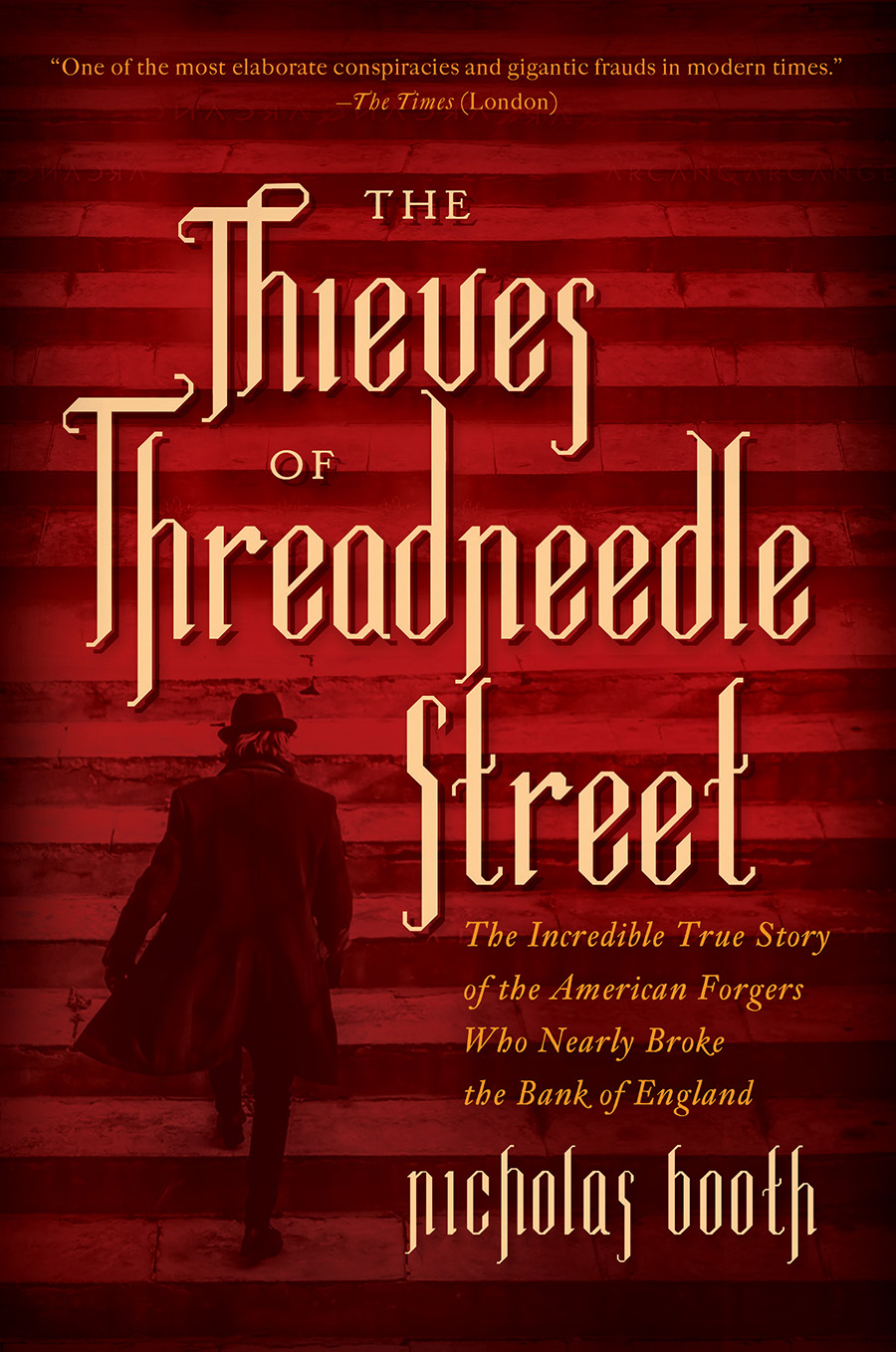

THE Thieves OF

Threadneedle

Street

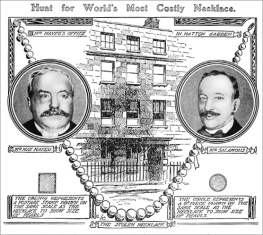

The Incredible True Story of the American Forgers

Who Nearly Broke the Bank of England

Nicholas Booth

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

For Sarah, my everything

THE THIEVES OF THREADNEEDLE STREET

Pegasus Books Ltd

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2016 by Nicholas Booth

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition November 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any fonn or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written pennission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-240-0

ISBN: 978-1-68177-284-4 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

The following narrative is based on several sources. These include official court transcripts, prosecution briefs, witness statements, timelines, detective reports, diaries, letters, telegrams and, of course, contemporary newspaper accounts. Much of this material especially in the archives of the Bank of England has never been examined before.

For reasons which will become clear in the text, I have been very careful in using the forgersown various confessional autobiographies in the narrative which follows, noting their tendencies to exaggerate. Others, writing years after the events, remembered things demonstrably wrongly. More memorable episodes are clearly recalled, but the chronology is invariably incorrect. In other cases, the converse is true.

Wherever possible, I have tried to ensure that the events described were at least verified by more than one source. Given the passage of time, such backup is sometimes impossible to obtain. The more fantastical claims of the forgers, their associates and the detectives who chased them as well as, more obviously, particularly excitable press coverage, cannot be taken at face value. Oddly, a number of the most remarkable stones are confirmed in contemporaneous accounts.

As a result, I have used a standard litmus test: extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence not least, as one of the witnesses noted towards the end of their trial at the Old Bailey, because the whole of the forgersconduct was extraordinary.

FOR LACK OF A NAIL

For lack of a nail the shoe was lost

For lack of a shoe the horse was lost.

For lack of a horse the rider was lost.

For lack of a rider the message was lost.

For lack of a message the battle was lost.

For lack of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the lack of a horseshoe nail.

Thus, a conspiracy which must have required months of work, the most patient ingenuity, sustained management, and the expenditure of a large capital, has suddenly collapsed for lack of a nail and the whole labour is lost.

The Times, Tuesday, 4 March 1873

Saturday, 1 March 1873

Cashiers Department, Bank of England, Threadneedle Street,

City of London. 10 a.m.

When he looked at it again, a cold shiver enveloped the deputy chief cashier of the Bank of England. The certificate in his hand was, at face value, a simple piece of paper, a glorified IOU known as a bill of exchange that had been accepted, stamped and its equivalent monetary value long since paid out. To his horror, Frank May had found it was counterfeit.

At first, he thought he had made a mistake. Diligently, he had checked and cross-referenced and come in early on this Saturday to pull the files just to make sure. To his growing dismay, he found he was not wrong. A sense of panic began to engulf him. Throughout his two decades working here, the cashier had never come across anything like this. It did not make any sense. He thought it had to be an oversight, but now, sitting quietly in his office, there could be no doubt. It was an elaborate and almost perfect forgery and one with terrible consequences.

When he had first come across the bill, he saw there was a date missing. Whoever had accepted it must not have noticed. That in itself was unusual, but then the more he looked into it, the more his suspicions gelled into complete and utter certainty. So, too, were other bills the cause of his growing disquiet. There was a whole slew of forgeries, increasing in value and number over the last few weeks. Most had passed through this building unnoticed and only by accident had he stumbled across this latest one.

Wondering what on earth was behind it all, Frank May decided he had better act before it was all too late if it wasnt already. Grabbing his hat and coat, the cashier made his way to the bank that had blithely cashed this particular forgery in all good faith. He looked up at the clock in the main entrance. He had better hurry, or else they whoever the hell they were would get away with 1 million or more, if they had not already done so.

Bills of exchange represented one of the greater innovations of nineteenth-century finance. They were essentially glorified credit notes sanctioned by reputable merchants who guaranteed them like post-dated cheques. They allowed for the ease and smooth flow of international trade via banks, a Victorian version of wiring money in advance. Today, similar transfers would be carried out electronically in the blink of an eye. Then, in the late Victorian age of steam and telegraph, the preferred method of redeeming such bills was from personal presentation. Providing the bearer was trusted, both he for it was invariably a male domain and the bill he presented were accepted at face value. More often than not, the accepting clerk would blithely rubber-stamp them.

The whole system was based on trust. It was a measure of Londons financial standing that a simple piece of paper with a reputable bankers signature was as honest and liquid as a banknote. A bill on London, as it was known, was every bit as solid as coins and notes of Her Majestys realm.

In recent years, bankers had been keen to discount them that is, they would offer real money at a percentage lower than the bills stated value. They would then recover the full amount from whoever had originally incurred that debt and issued them. That was what Frank May was now attempting to do, essentially balancing his ledger.

Crucially, their acceptance centred on a signature. That was all that was needed to endorse them. In the City of London, the whole process, from acceptance to discounting, was underwritten by the Bank of England, the fulcrum of the most stable financial system in the world. As a result, discount houses had sprung up all over the City. Most were located across the way in Lombard Street, where Mr May was now headed to the Continental Bank at No. 79.

Somebody had clearly subverted the whole process. This particular bill had a date missing. So it was fairly obvious that the acceptances were not genuine. No reputable banker would have allowed it to pass unless they were incompetent, which Mr May very much doubted. That was why he needed to find out more from the bankers who had discounted this specific bill and whether their signature of acceptance was genuine.

[Those] last seven words give the key to the whole mystery was how one of the forgers behind it later explained it, a riddle that the deputy chief cashier of the Bank of England was now determined to resolve as he left the building, fearful of what he might find.

Next page