NEW MERMAIDS

General editors:

William C. Carroll, Boston University

Brian Gibbons, University of Mnster

Tiffany Stern, University of Oxford

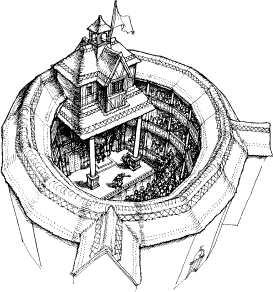

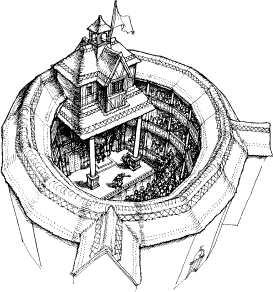

Reconstruction of an Elizabethan theatre

by C. Walter Hodges

NEW MERMAIDS

The Alchemist

All for Love

Arden of Faversham

Arms and the Man

Bartholmew Fair

The Beaux Stratagem

The Beggars Opera

The Changeling

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside

The Country Wife

The Critic

Doctor Faustus

The Duchess of Malfi

The Dutch Courtesan

Eastward Ho!

Edward the Second

Elizabethan and Jacobean Tragedies

Epicoene or The Silent Woman

Every Man In His Humour

Gammer Gurtons Needle

An Ideal Husband

The Importance of Being Earnest

The Jew of Malta

The Knight of the Burning Pestle

Lady Windermeres Fan

London Assurance

Love for Love

Major Barbara

The Malcontent

The Man of Mode

Marriage A-La-Mode

A New Way to Pay Old Debts

The Old Wifes Tale

The Playboy of the Western World

The Provoked Wife

Pygmalion

The Recruiting Officer

The Relapse

The Revengers Tragedy

The Rivals

The Roaring Girl

The Rover

Saint Joan

The School for Scandal

She Stoops to Conquer

The Shoemakers Holiday

The Spanish Tragedy

Tamburlaine

The Tamer Tamed

Three Late Medieval Morality Plays

Mankind

Everyman

Mundus et Infans

Tis Pity Shes a Whore

The Tragedy of Mariam

Volpone

The Way of the World

The White Devil

The Witch

The Witch of Edmonton

A Woman Killed with Kindness

A Woman of No Importance

Women Beware Women

NEW MERMAIDS

FRANCIS BEAUMONT

THE

KNIGHT OF

THE BURNING

PESTLE

2nd edition

edited by Michael Hattaway

Professor of English Literature

University of Sheffield

CONTENTS

Anyone who edits The Knight of the Burning Pestle must be grateful to predecessors, in my case to H. S. Murch and Cyrus Hoy for their editions of the play, and to theatre historians like Andrew Gurr who, in recent years, have refined greatly our understanding of the dramatic milieu. T. W. Craik and Roger Hardy supplied references for the first edition, Malcolm Jones for this one. In 1960 John Dawick invited me to act in a student production; later Brian Morris encouraged me to edit the play, Michel Bitot and Pierre Iselin rekindled my interest by invitations to lecture in France, and Brian Gibbons has overseen this revised edition with his customary insight and toleration. My son Rafe has observed my labours with a degree of quizzicality, my former student Judi Shepherd has given me inestimable support.

M. H.

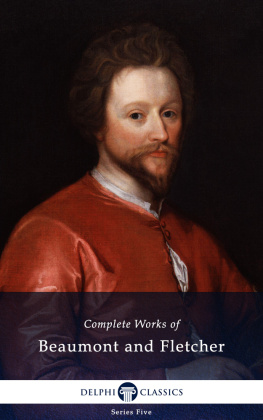

Francis Beaumont was born about 1585 in Leicestershire at Grace-Dieu, the country seat of his family. His grandfather and father had attained distinction as judges, and he evidently intended to continue the family tradition, for, having been admitted in 1597 as a gentleman commoner of Broadgates Hall (now Pembroke College), Oxford, in 1600 he left the university without taking a degree to become a member of the Inner Temple in London. Like many of his contemporary dramatists, his first publication was an erotic poem, Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1602).

Although three of the four seventeenth-century editions of the play attribute The Knight of the Burning Pestle to Beaumont and Fletcher, most modern critics, by means of an analysis of the plays unity of conception and of the style of its verse, have ascribed it to Beaumont alone. This ascription is convincingly supported by Cyrus Hoys analysis of the linguistic habits of the authors who contributed to the Beaumont and Fletcher canon. The relevant evidence and argument, which centres on incidentals such as the authors use of ye, third person singulars terminating in -th, and contractions (ith, has, etc.), are set out in two important articles: The Shares of Fletcher and his Collaborators in the Beaumont and Fletcher Canon, (I) and (III), Studies in Bibliography, VIII and XI (1956 and 1958), 12946 and 85106.

The first edition of the play is a quarto dated 1613 (Q1). There is no mention of the authors name on the title-page, nor any indication of where the play had been performed. The terminus ad quern is therefore 1613, and the terminus a quo is 1607, the date of The Travels of the Three English Brothers, the latest of the plays referred to in the play. Within the text the three most important pieces of evidence for establishing the date more precisely are:

(i) The statements in the publishers Epistle that he had fostered it privately in his bosom these two years, and that it was the elder of Don Quixote above a year (1425). The first statement would imply that the play dates from 1611, likewise the second, for Sheltons translation of Cervantes novel was entered on the Stationers Register on 19 January 161011 and published in 1612. In all probability, however, the publisher, Burre, is referring not to the date of the first production, but to the date at which Robert Keysar, a goldsmith who financed the Children of the Revels, rescued the text from perpetual oblivion. Keysar presumably provided Burre with a manuscript of the play sometime after it had become clear that the play would not do well in the theatre but after Beaumont had established his reputation. This part of the evidence therefore points to a date before 1611.

(ii) The Citizen remarks at IV, 4950: Read the play of The Four Prentices of London, where they toss their pikes so. The earliest surviving edition of this play is 1615. However, Fleay, in A Biographical Chronicle of the English Drama (London, 1891), i, 182, argued that the Citizens reference is to a putative lost edition of 1610, for in the Epistle to the 1615 edition of The Four Prentices there is an allusion to the recent revival of the practice of arms in the Artillery Garden, a revival which, as Stows continuator noted, occurred in 1610. Fleay accordingly dated the play 1610. His argument is, however, based on evidence which comes only from the Epistle, not from that part of the play which was acted. Moreover, in the same Epistle Heywood says the play was written in my infancy of judgement in this kind of poetry some fifteen or sixteen years ago, and an earlier part of this play, Godfrey of Bulloigne, had been entered on the Stationers Register as early as Finally, the context of the Citizens remark is ironical as it suggests that he is treating a play which he had probably seen but not necessarily read as reliable history.

(iii) The most important evidence, the Citizens reference to This seven years there hath been plays at this house (Induction, 67), which would fit almost exactly the years 16008 when the Children of the Revels were playing at the Blackfriars playhouse before it was taken over by the Kings Men. Moreover the dedicatee is Robert Keysar, who had managed this troupe from about 1606.

The weight of the evidence therefore points to an original performance in 1607 or 1608, that is some seven years after the Children of the Revels had moved to Blackfriars. This is confirmed by the reference to Moldavia (IV, 58 and see IV, 34n.): the Prince of Moldavia was at Court in 1607. The other evidence for dating, the publication of some of Merrythoughts songs in 1609, is inconclusive, as these were popular tunes and almost certainly known before their publication. If, however, the later date of 161011 is accepted, the play may have been performed at the short-lived Whitefriars where the Children of the Revels (again under Keysar) performed from 1609 to 1614.

Next page