Contents

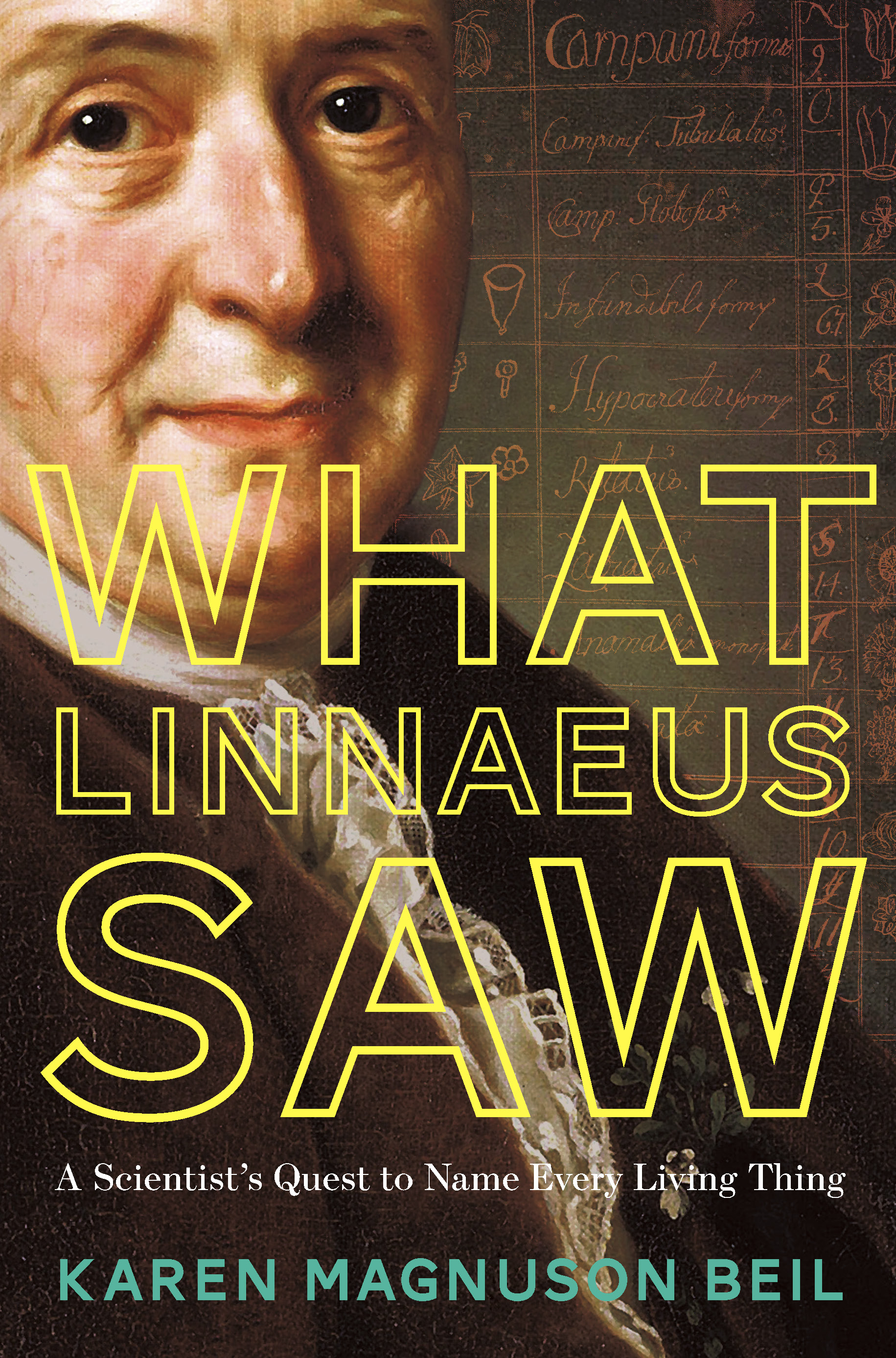

WHAT

LINNAEUS

SAW

A Scientists Quest

to Name Every Living Thing

KAREN

MAGNUSON BEIL

Norton Young Readers

An Imprint of W.W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

... though we be confined to one spot, one corner of the earth, we may examine the great and various stores of knowledge, and therein behold the immense domains of nature.

CARL LINNAEUS, HIS FIRST LECTURE AS A PROFESSOR, AN ORATION CONCERNING THE NECESSITY OF TRAVELING IN ONES OWN COUNTRY, 1741

E ver since he was old enough to walk and pull weeds, Carl had helped his father in the garden. Now sixteen years old, at home for summer vacation in 1723, he kept his eye on a pumpkin plant. His father had great hopes for it.

Flowers and fruit trees stretched out in dizzying variety, more than 220 different kinds. The garden belonged to the parsonage, which stood next to the church in Stenbrohult, Sweden, where Carls family lived. His father, Nils Linnaeus, was the pastor, and Carl himself was studying to join the clergy.

The land sloped toward a lake, the opposite bank rising to a hilly ridge. At a time when only grand estates had lavish ornamental gardens, this yard alongside the simple wooden parsonage was bursting with flowers and exotic trees, as well as practical kitchen plants to feed the family. Pastor Linnaeuss garden was said to be one of the best-stocked in this corner of Sweden.

Carl sketched this map of Stenbrohult showing the parsonage where he grew up, his fathers church (a), gardens (b), and Lake Mckeln (c). His father grew fruit trees including apples, pears, cherries, and plums; gooseberries, raspberries, and musk strawberries; vegetables such as turnips, artichokes, horseradish, spinach, and asparagus; flowers including tulips, daffodils, violets, and salvia; and rare trees including mulberry, fig, and dwarf almond.

Carl was happy to spend his summer here. At school, the boysand even the masterscalled him the Little Botanist. This garden was Carls favorite place to be, a place where he routinely saw things that astonished him. And made him wonder...

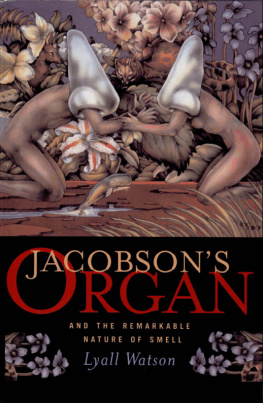

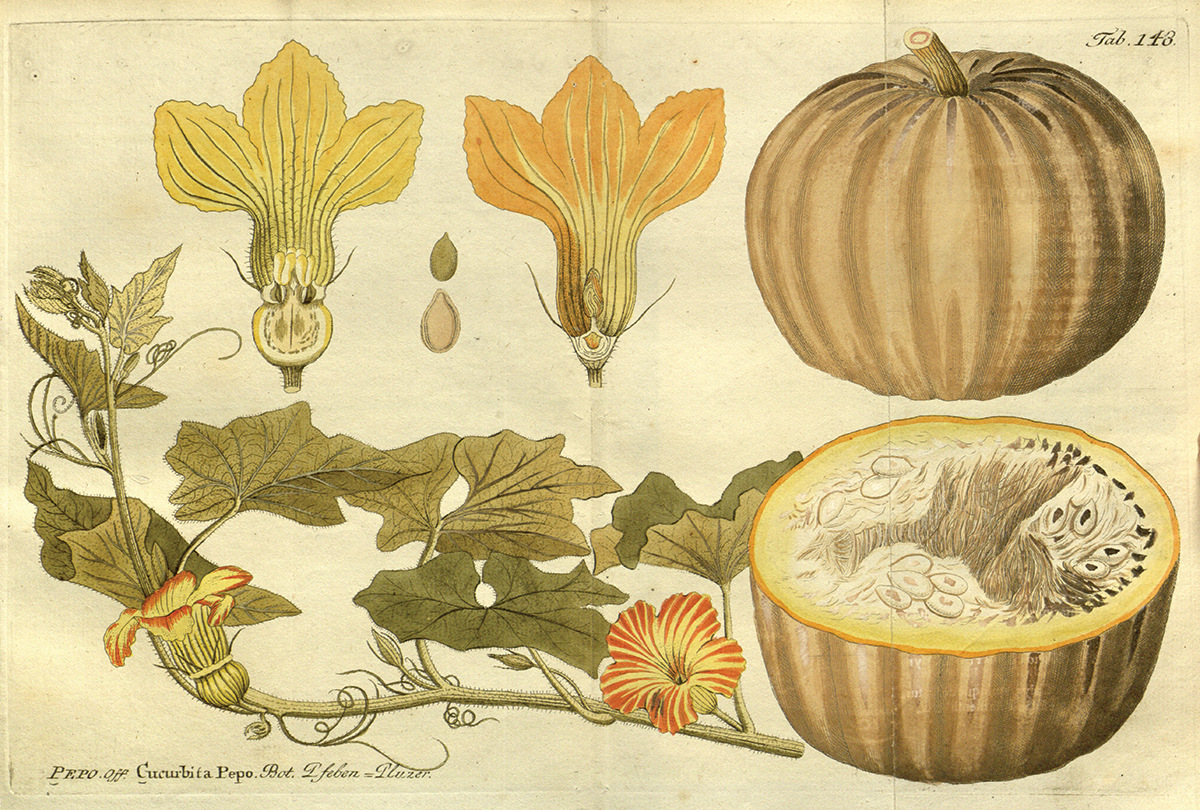

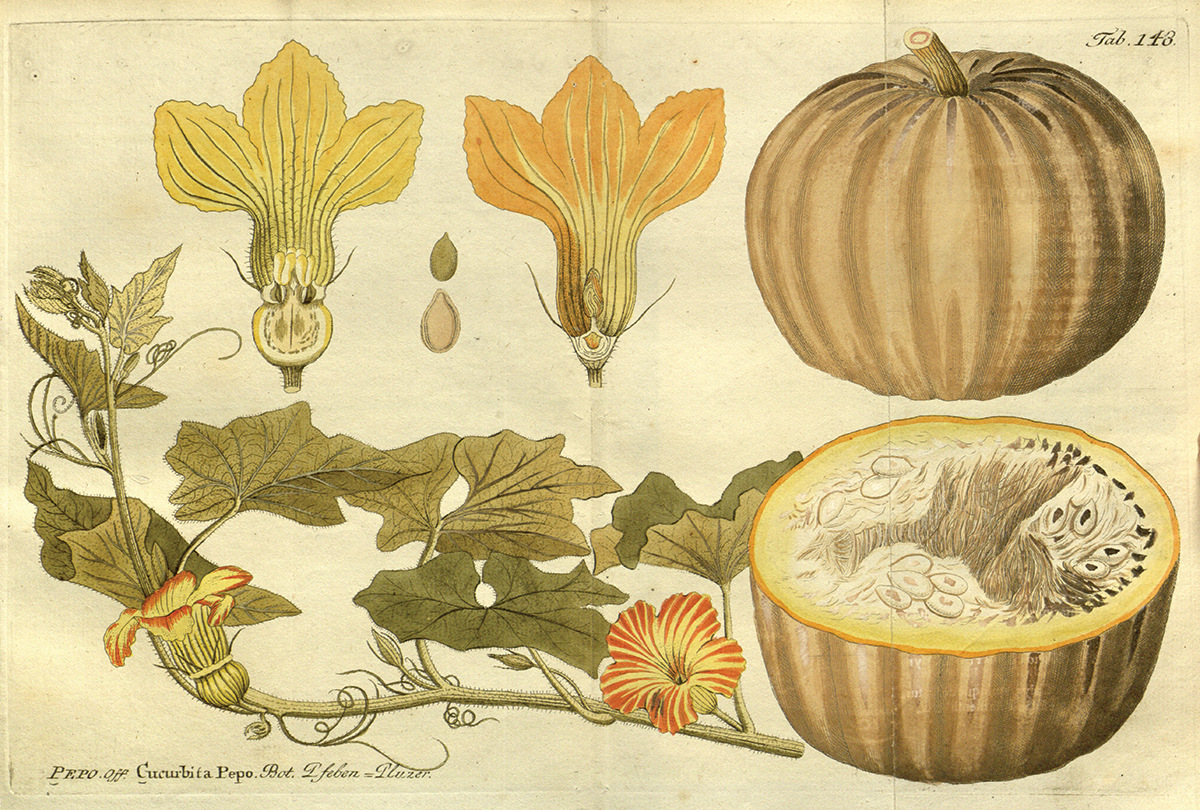

The pumpkin plantwith its green vines, hairy leaves, and bright yellow flowerslooked as expected. Up close, with its prickly leaves pushed aside, he would have seen two kinds of flowers growing on the plant. One kind grew on a long, skinny stem. Inside its petals, several thread-like filaments clumped together as one, coated with a powdery yellow dust. The second kind of flower sat on a shorter, thicker stem with a berry-shaped bulge at its base. Inside that flower stood a short stalk with a sticky, bumpy crown on top. Nils taught his son the Latin names for these structures. Even there in the Swedish farm country, they knew that this North American plant typically had two different flowers, but they had no idea why those flowers were different or what their functions were.

At Nilss direction, every morning any new pumpkin flower with thread-like filaments, called stamens, was carefully snapped off. Any flower containing a short stalk, or pistil, with a bulge at its base was left to bloom. Experience growing other vines with two types of flowers, such as cucumbers and melons, had taught Nils that only the flowers with little green bulges at their bases would ripen and mature into fruits. So it seemed reasonable to assume that removing the unwanted flowers would reduce competition for nutrients and cause the pumpkin plant to direct all its energy into the flowers with little green bulges.

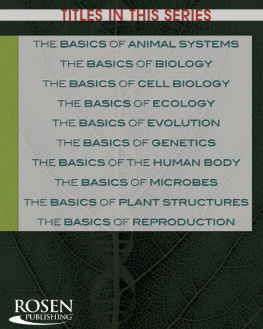

An 1804 illustration showing cross-sections of two kinds of pumpkin flowers: on the left, with pistil and bulge, and on the right, with stamens fused together and no bulge.

Pumpkins were among the food plants important in Carls mothers kitchen. His fathers goal was to present her with a harvest of big pumpkins. Day after day for the rest of the summer, skinny-stemmed pumpkin flowers were beheaded. However, by summers end, the garden revealed a puzzling result: no pumpkins. Not a single one.

It would be several years before Carl understood why his fathers pumpkin plants failed to make pumpkins that summer. Meanwhile, in September when the beech trees turned gold and days began to grow short, Carl had to leave once again. It had been nine summers since the day his parents first packed him off as a seven-year-old to the Vxj Cathedral School, to prepare him to follow his father into the clergy.

The thirty-mile trip took at least two days on horseback. The woods, the lake, the stony fields, and the garden with no pumpkins slipped into the distance as he made his way back to school alone.

A BRANCH OF THE FAMILY TREE

In the old Swedish name tradition, a child was given a first name plus a patronymic, which was derived from the fathers first name. So Linnaeus would have been known as Carl, the son of Nils, or Carl Nilsson. His sister would have been called Anna Maria Nilsdotter (Anna Maria, the daughter of Nils). In a tiny village like Stenbrohult, that was all theyd need.

Children born into families who could afford education required a formal school name, to distinguish them from classmates whose names and patronymics might be the same as their own. This applied only to boys, because in the early eighteenth century, girls were rarely given the opportunity to go to school.

School names were often based on birthplace or nature. For instance, when Carl Linnaeuss father, Nils Ingemarsson, attended Lund University, he chose to call himself after a stately old linden tree on his familys farm. He took the trees regional name, lin, added the Latinate ending -aeus, and became Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus. Nilss child Carl was Carl Nilsson Linnaeus. When Carl married Sara Lisa Moraea, she retained her name, as was the custom, but their children took their fathers last name, his daughters names ending in the feminine form, Linnaea.

When King Adolf Fredrik ennobled Carl Linnaeus in 1757 (it became official four years later), the professor adopted a new name: von Linn. Why he chose that name is not known, but it reflected the trend among the Swedish nobility toward all things French. Linnaeus provided a sketch upon which the royal herald based his coat of arms, designed to represent nature: my little Linnaea in the helmet, with the shield divided into three fields: black, green, and redthe three kingdoms of Naturesuperimposed on an egg. However, there was a dispute. Linnaeuss original sketch showed only the yellow yolk, and he was miffed when the royal herald misunderstood the symbolism and drew the entire egg.

Next page