Contents

Guide

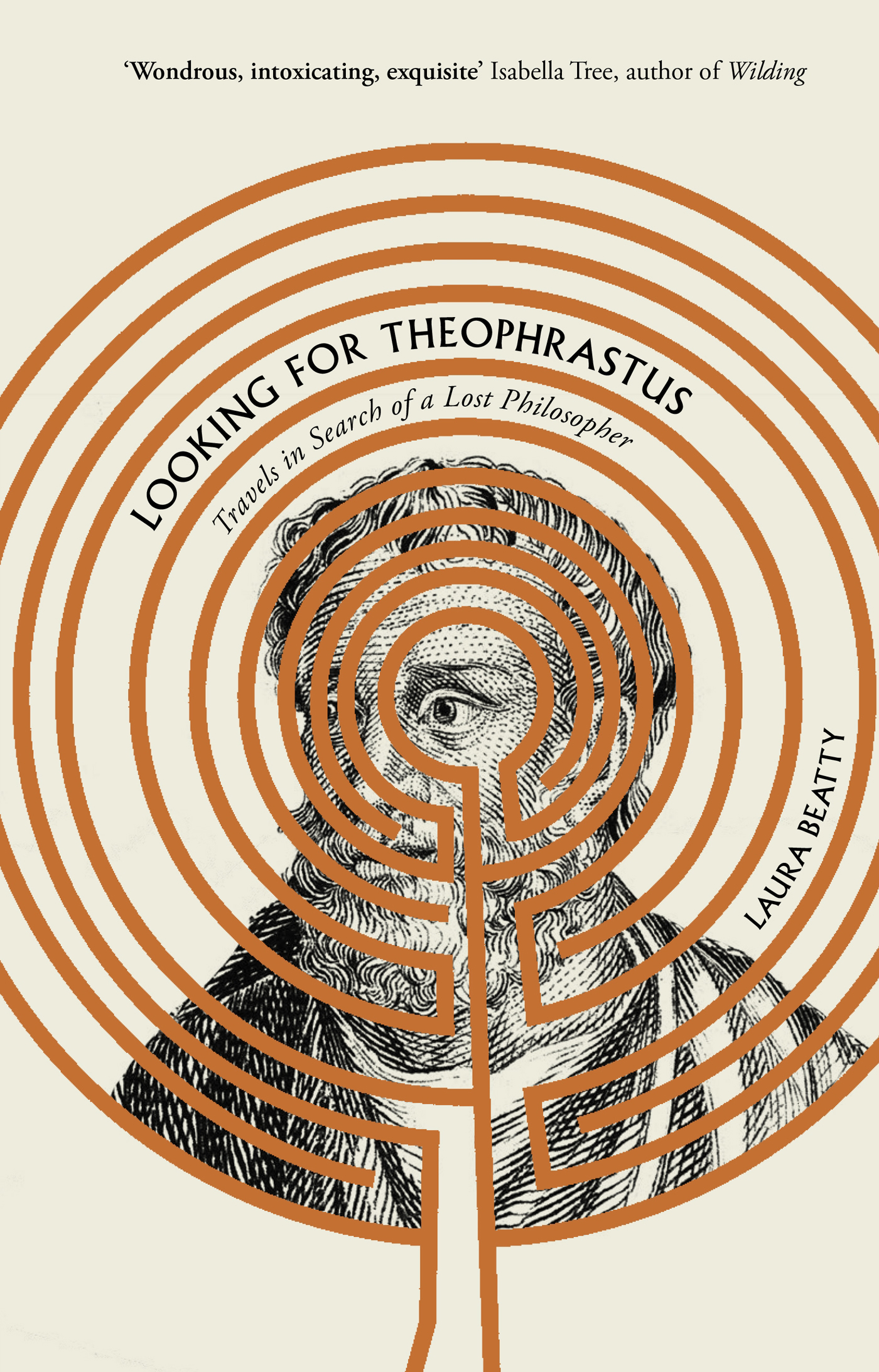

Also by Laura Beatty

Lost Property

Darkling

Lillie Langtry

Pollard

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Laura Beatty, 2022

The moral right of Laura Beatty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

With thanks to Cambridge University Press for permission to quote from Theophrastus: Characters, translation by James Diggle.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 436 9

EBook ISBN: 978 1 83895 437 6

Design www.benstudios.co.uk

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To Rupert

And might it not be that we also have appointments to keep in the past, in what has gone before and is for the most part extinguished, and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the far side of time, so to speak?

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz

I

The Man

If it happened, then someone must have seen it. A fisherman coming home across an evening sea, one early star burning on the horizon and the sky still light. There, ahead of him, something bobbing on the water the head, a little pale balloon with its ribbon of blood unwinding behind it all the way to the horizon.

Or maybe it wasnt like that. Maybe the fisherman heard it before he saw it; first thinking it a seagulls cry, but then thinking, no it isnt that, someone is singing. So he looked around to see where it came from, this strong, unearthly song. Could it be coming from there, that little collection of flotsam? It is likely that there was other detritus from the murder. The flesh and bones, the coils of things normally hidden and now spilled out, floating on the seas surface, rising and falling with the swell. There, in the middle of it all, would have been the head, singing. Because that is the important point not the murder, not the women tearing him apart with maddened hands, but the fact that the song refused to die. It went on unchanged, pouring out of the dismembered mans mouth as if nothing had happened, on and on, all the way down the Hebros river and out across the sea, until the head landed, still singing, on a beach on the island of Lesbos. That was the greatest outrage, that one human beings song could do that, cheat time that Orpheus music was so free it was death-proof.

*

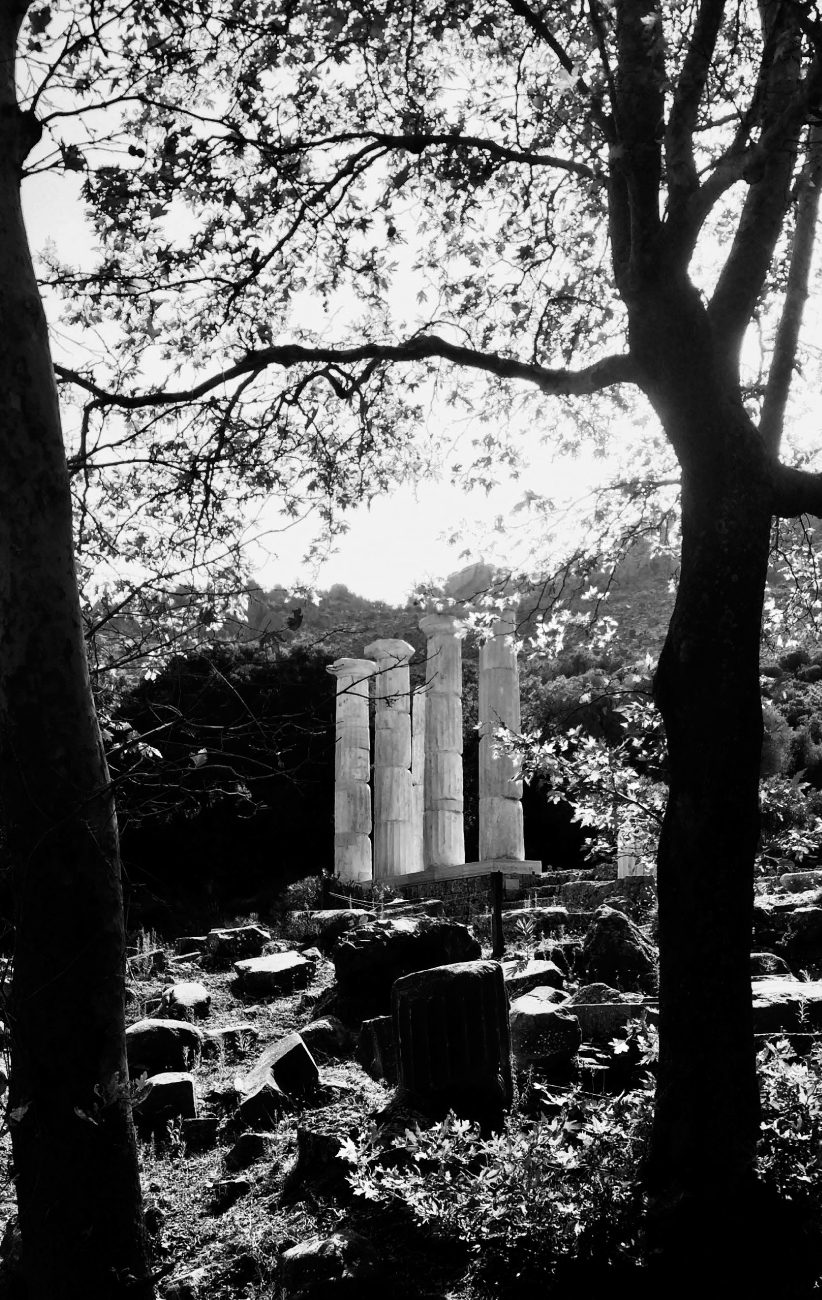

It is evening, October and windy; Im standing at the rail of a ship, a ferry, waiting to leave Piraeus for Lesbos, where the head of Orpheus came to rest. Below me, on the empty quayside, one or two cars are parked, men are set up for fishing over propped rods. The dark is fast coming down. Somewhere there is music playing Greek music, with its strange running and halting rhythms. I lean and listen to the tune, now fast, now slow, now fast again, on its endless, trance-inducing round.

At the docks abrupt edge, a family, with a set of white plastic tables and chairs, dines quietly, as if they were in their own home. The music is coming from the open window of their parked car, as they pass each other salads in little Tupperware dishes. Above them, the ferry which is in proportion to the sea not the land bulks gigantic against the dock. It is not human in scale, so what on earth kind of journey are you taking, I find myself thinking, if this is your vehicle of choice?

Im going a long way much further than the 143 or so nautical miles between Athens and Lesbos. Im going back about 2,400 years to find someone, a philosopher whose work once burned itself across the sky of Western thought, and then somehow fell into darkness and was gone.

A forgotten philosopher? Why on earth would we need one of those, let alone one from so impenetrably far back in human history? Well, because this one is different: less titanic perhaps but more modern in his thinking, more recognizable and therefore more relevant to now. For a start, he comes not from the grandeur and confidence of classical Greece, but from the moment of muddle and compromise just after it, when Athens grip on its own world was slipping and the dream of democracy was dying.

I was familiar enough with classical Greece, with its myths and its poetry, its confident statues and its architecturally astonishing temples. I knew it first, as a child, in its mythic mode, as a place of slippage a Narnia for grown-ups, whose woods were full of centaurs and whose people turned into trees, or stones. Then, later, I knew it in its heroic and tragic mode, as a place of grandeur and clanging bronze, governed by fate and made of gold, very, very far back in time and unassailable in its almost perfection. What it never was, or what I could never see, was its ordinary mode, its day to day.

Then, about ten years ago, I came across something else, something very unexpected. It was a little green book of character sketches and the sketches were of ordinary people people like the Chatterbox, who sits next to a stranger hes never met before and first launches into singing his own wifes praises, then recounts the dream he had last night, then describes in every detail what he had for dinner. Then, as no one has managed to stop him, he carries right on saying things like, People nowadays are far less well-behaved than in the olden days The city is crammed with foreigners. A little more rain would be good for the crops.

These people were out and about in the marketplace, in and out of each others houses for dinner. They were gossips and flatterers, and farmers, and city boys, all talking in their own ordinary voices, in their ordinary clothes, among the clutter of their ordinary possessions.

How could something so long ago feel so immediately present? It was as if all the previously invisible, unmentioned and unimaginable humdrum of unassailable Athens had catapulted itself suddenly into my writing room. I didnt know what to make of it. Where, in the canon, did it fit? It was so different. It read like something out of a novel but it was two thousand years too early. I looked again at the name on the cover: Theophrastus. It wasnt like anything else Id ever read. I sat holding the book in my hands and wondering about its author.

How do you know how to do this, Theophrastus? What is this? Ive been reading for years and Ive never even heard of you. Who exactly are you?