Contents

1

Forget not Mee & My Garden

2

The bright beam of gardening

3

My harmless sexual system

4

Pray go very Clean, neat & handsomely Dressed to Virginia

5

All gardening is landscape-painting

6

Send no Seeds for him all is att an End

7

Commonwealth of Botany

8

The English are all, more or less, gardeners

9

See what a complete empire we have now got within ourselves

10

Ye who oer Southern Oceans wander

11

An Academy of Natural History

12

As good-humoured a nondescript Otatheitan as ever!

13

Loves of the Plants

About the Book

One January morning in 1734, cloth merchant Peter Collinson hurried down to the docks at Londons Custom House to collect cargo just arrived from John Bartram, his new contact in the American colonies. But it was not reels of wool or bales of cotton that awaited him, but plants and seeds...

Over the next forty years, Bartram would send hundreds of American species to England, where Collinson was one of a handful of men who would foster a national obsession and change the gardens of Britain forever, introducing lustrous evergreens, fiery autumn foliage and colourful shrubs. They were men of wealth and taste but also of knowledge and experience, like Philip Miller, author of the bestselling Gardeners Dictionary, and the Swede Carl Linnaeus, whose standardised botanical nomenclature popularised botany as a genteel pastime for the middle-classes; and the botanist-adventurer Joseph Banks and his colleague Daniel Solander who both explored the strange flora of Tahiti and Australia on the greatest voyage of discovery of modern times, Captain Cooks Endeavour.

This is the story of these men friends, rivals, enemies, united by a passion for plants whose correspondence, collaborations and squabbles make for a riveting human tale which is set against the backdrop of the emerging empire, the uncharted world beyond and London as the capital of science. From the scent of the exotic blooms in Tahiti and Botany Bay to the gardens at Chelsea and Kew, and from the sounds and colours of the streets of the City to the staggering vistas of the Appalachian mountains, The Brother Gardeners tells the story how Britain became a nation of gardeners.

About the Author

Andrea Wulf was born in India and moved to Germany as a child. She trained as a design historian at the Royal College of Art and is the co-author (with Emma Gieben-Gamal) of This Other Eden: Seven Great Gardens and 300 Years of English History. She has written for the Sunday Times, the Financial Times, The Garden, Kew Magazine, the Architects Journal, and reviews for several newspapers, including the Guardian, the Times Literary Supplement and the Mail on Sunday. She regularly appears on BBC radio and television, and was a judge for the Benjamin Franklin House Literary Prize 2008.

ALSO BY ANDREA WULF

This Other Eden: Seven Great Gardens and 300 Years of English History

(with Emma Gieben-Gamal)

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN 9781446439562

Version 1.0

Published by Windmill Books 2009

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Copyright Andrea Wulf 2008

Andrea Wulf has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by William Heinemann

Windmill Books

The Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Windmill Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at

global.penguinrandomhouse.com

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099502371

To Brigitte and Herbert

Our England is a garden, and such gardens are not made

By singing: Oh, how beautiful! and sitting in the shade,

While better men than we go out and start their working lives

At grubbing weeds from gravel-paths with broken dinner-knives.

Rudyard Kipling, The Glory of Gardens

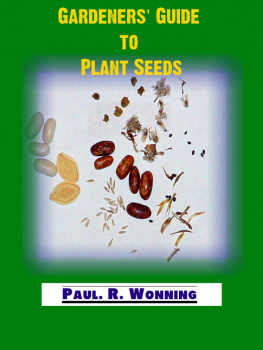

A Note on the Plant Names

In order to avoid the unwieldy use in the text of both the common and Latin names of plants, I have used either one or the other depending on the name by which a plant is most likely to be known. However, every plant is listed in the index under its common name (with the Latin name in brackets) and under its Latin name (with its common name in brackets).

When eighteenth-century correspondents only used common names of a genus such as Solomons seal and it has been impossible to identify the exact plant species, this name is used throughout the book.

Additional information on the plants that played an important role in the eighteenth-century garden and their introduction to Britain can be found in the Glossary at the end of the book.

Introduction

But here it is worth noting a minor English trait which is extremely well marked though not often commented on, and that is a love of flowers. This is one of the first things that one notices when one reaches England from abroad, especially if one is coming from southern Europe.

George Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, 1941

When I left my home town of Hamburg more than a decade ago, few of my friends possessed a garden. Even now, they mostly still prefer to live in huge apartments, putting off buying houses with outside space for their retirement. In Germany, gardening is often considered an occupation for pensioners. I certainly thought of it like that. It meant growing a few pansies in almost bare flowerbeds, planting out your allotment in regimented rows, or obsessively trimming your hedge with a ruler (on one occasion a neighbour sent a policeman to our house to inform my parents that our unruly hedge was at least four inches too close to the pavement).

I was therefore amazed, when I moved to London in the mid nineties, to find a nation obsessed with gardening. The shelves of my local newsagent groaned beneath lavish displays of gardening magazines; everywhere I went I saw signs for garden centres, and my new friends all seemed to think that the best way to spend a weekend was to visit the grounds of a stately home (unless they had an allotment, in which case the thrill of digging and weeding could not be surpassed). It seemed that everybody had a garden, and if they didnt, they wanted one: young and old, fashionable and staid, middle-class or working-class. At parties I listened for hours to twenty-something Londoners rave about plants or moan about horticultural disasters. I went with a trendy graphic designer to a nightclub, only to listen for half the evening to the minute details of the yield of his vegetable plot. On one occasion, a beautiful and perfectly groomed young woman told me that it was pointless throwing snails over the garden wall on to the railway embankment because they would return she knew for certain because she had marked their shells with white paint.