PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2018 by J. G. Cottasche Buchhandlung

Translation copyright 2020 by Shaun Whiteside

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Originally published in German as Zeit der Zauberer by Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING- IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Eilenberger, Wolfram, 1972 author. | Whiteside, Shaun, translator.

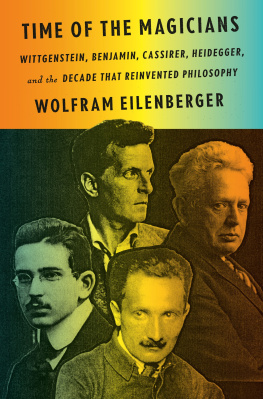

Title: Time of the magicians : Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the decade that reinvented philosophy / Wolfram Eilenberger ; translated by Shaun Whiteside.

Other titles: Zeit der Zauberer. English

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2020. | Translation of: Zeit der Zauberer. Stuttgart : Klett-Cotta, c2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050893 (print) | LCCN 2019050894 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525559665 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525559672 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Philosophy, GermanHistory20th century. | GermanyHistory19181933.

Classification: LCC B3181 .E5513 2020 (print) | LCC B3181 (ebook) | DDC 193dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050893

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050894

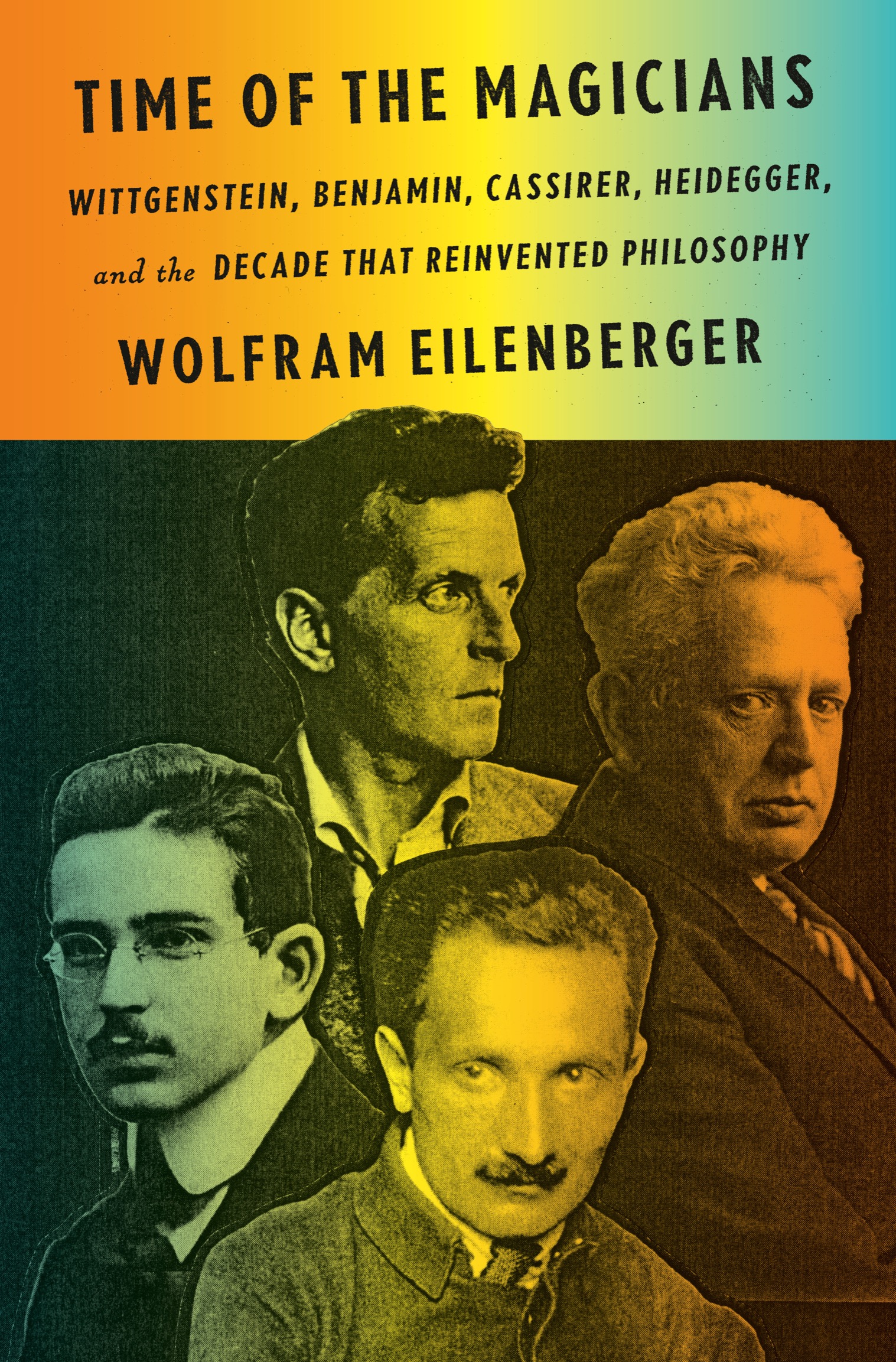

Cover design: Stephanie Ross

Cover images: (clockwise from top) Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein, Moritz Nhr / IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo; Ernst Cassirer, Transocean 1931 / ullstein bild / Getty Images; Martin Heidegger, Apic / Getty Images; Walter Benjamin, J. Ll. Bans / age fotostock / Alamy Stock Photo

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

For Eva

The best that we have from history is the enthusiasm that it stimulates.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Maxims and Reflections

CONTENTS

I.

PROLOGUE

THE MAGICIANS

THE ARRIVAL OF GOD

D ON T WORRY , I know youll never understand it. This sentence concluded what was probably the most peculiar oral exam in the history of philosophy. Appearing for his doctoral examination at Cambridge on June 18, 1929, before a panel consisting of Bertrand Russell and G. E. Moore, was a forty-year-old former multimillionaire from Austria who had for the previous ten years been working chiefly as a primary school teacher. His name was Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein wasnt some obscure returning Cambridge student. On the contrary, from 1911 until just before the outbreak of the First World War, he had studied there with Russell and had quickly become a cult figure, known for both his obvious brilliance and his waywardness. Well, God has arrived, I met him on the 5:15 train, John Maynard Keynes wrote in a letter dated January 18, 1929. Keynes, at the time probably the most important economist in the world, met Wittgenstein by chance the day after his return to England. It says a great deal about the intimate, rumor-filled atmosphere of university life at the time that Wittgensteins old friend G. E. Moore was on the same train from London to Cambridge.

But it would be a mistake to think that the atmosphere in the compartment was entirely convivial. Wittgenstein at least was not given to small talk or other social niceties. The genius from Vienna was prone to sudden outbursts of fury, and could be extremely unforgiving. A single word out of place or jocular observation could lead to years of rancor, indeed to a breakdown in relationsas had happened several times with Keynes and Moore. However: God was back! And accordingly, joy was unconfined.

The next day, a meeting of the Apostlesa highly elitist, unofficial students club notorious at the university for the sexual proclivities of its memberswas called in Keyness house to welcome the prodigal son. At a ceremonial dinner Wittgenstein was promoted to the rank of Angel, an honorary senior member of the society. Most of the groups members hadnt met for more than a decade. A lot had happened in the meantime, but to the Apostles, Wittgenstein appeared almost unchanged. It wasnt just that he was wearing his typical outfit of an open-necked shirt, gray flannel trousers, and heavy, agricultural-looking boots. Physically, too, the years seemed to have passed without leaving a trace. At first sight, he looked like one of the gifted students who had also been invited, and who had previously known the strange man from Austria only from their professors stories. And, of course, that he was the author of the Tractatus logico-philosophicus, the legendary work that had shaped, if not actually dominated, philosophical discussion in Cambridge for several years. None of those present would have claimed that they had even begun to understand the book, but this fact only boosted its fascination.

Wittgenstein had finished the book in 1918 as a prisoner of war in Italy, convinced that he had found the solution to philosophical questions on all essential points, and thus decided to turn his back on the discipline. Only a few months later, as the heir to one of the wealthiest industrial families in Europe, he transferred his entire inheritance to his siblings. As he told Russell in a letter at the time, from now onplagued as he was by severe depression and thoughts of suicidehe would support himself with honest toil. He would become a teacher at a provincial primary school.

Wittgenstein was back in Cambridge. Back, it was said, to philosophize. The genius, now forty years old, had no academic title and was utterly penniless. The little money that he had managed to save lasted only a few weeks in England. Cautious inquiries about the willingness of his siblings to help him out financially were intemperately dismissed. Will you please accept my written declaration that not only I have a number of wealthy relations, but also that they would give me money if I asked them to. BUT THAT I WILL NOT ASK THEM FOR A PENNY, Wittgenstein wrote to Moore the day before his oral examination.

What was to be done? No one in Cambridge doubted Wittgensteins exceptional gifts. Everyone, including the most influential figures at the university, wanted to keep him there. But without an academic title, it proved institutionally impossible to find a research grant, let alone a regular teaching post, for the former dropout, even in the clubby atmosphere of Cambridge.

In the end they hatched a plan: Wittgenstein would submit the Tractatus logico-philosophicus, his first and so far his only book, as a doctoral thesis. Russell had personally advocated for its publication in 19211922, and had written a foreword to help the process along, since he considered the work of his former pupil far superior to his own groundbreaking studies in the philosophy of logic, mathematics, and language. No wonder, then, that upon entering the examination room Russell swore that he had never known anything so absurd in my life. Still: an exam is an exam, and after a few minutes of friendly inquiry Moore and Russell started asking some serious questions. These concerned one of the central riddles of the