STUDIES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF WITTGENSTEIN

ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS

WITTGENSTEIN

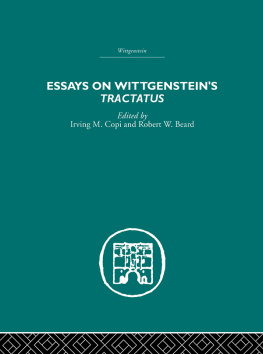

| Essays on Wittgensteins Tractatus | Edited by Irving M. Copi and Robert W. Beard |

| Marx and Wittgenstein: Social praxis and social explanation | D. Rubinstein |

| Studies in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein | Edited by Peter Winch |

| Wittgenstein: To follow a rule | Edited by Steven Holtzman and Christopher Leich |

| Wittgenstein: A critique | J.N. Findlay |

| Wittgenstein and Modern Philosophy | Justus Hartnack |

| Wittgensteins Philosophy of Language: Some aspects of its development | James Bogen |

| Wittgenstein and the Turning-Point in the Philosophy of Mathematics | S.G. Shanker |

STUDIES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF WITTGENSTEIN

Edited by

Peter Winch

First published in 1969

This edition first published 2006 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

1969 Peter Winch

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors and copyright holders of the works reprinted in the Wittgenstein series. This has not been possible in every case, however, and we would welcome correspondence from those individuals or organisations we have been unable to trace.

These reprints are taken from original copies of each book. In many cases the condition of these originals is not perfect. The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of these reprints, but wishes to point out that certain characteristics of the original copies will, of necessity, be apparent in reprints thereof.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Studies in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein

ISBN 0-415-38281-5 (volume)

ISBN 0-415-38278-5 (set)

Routledge Library Editions: Wittgenstein

Studies in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein

Edited by

PETER WINCH

First published 1969

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Peter Winch 1969

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism

ISBN 0 7100 6393 8

Peter Winch

THE essays in this volume are all new. Contributors were selected with a view to providing a fairly representative range of Wittgensteins philosophical interests but, once selected, they were left entirely free to write on what most interested them. There is, therefore, no claim to any systematic covering of the ground and, inevitably, some of Wittgensteins most central preoccupations are independently discussed by various individual contributors. This, I think, is in the spirit of Wittgensteins method, particularly in his later works, of passing over the same point again and again from different directions, thus building up a picture of its complex relations to other points of philosophical interest.

I shall try, in this Introduction, to give some account of the development of Wittgensteins treatment of certain central issues, relating these issues, where I can, to the points discussed by the other contributors. One of my main aims will be to combat the widespread view, which seems to me disastrously mistaken, that we are dealing with two different philosophers: the earlier Wittgenstein and the later Wittgenstein; hence my subtitle the Unity of Wittgensteins Philosophy. Of course, when I speak here of unity, I by no means wish to imply that we have to do with a single system of philosophy (like Spinozas, say), stretching from the Tractatus to and beyond Philosophical Investigations. On the one hand the ideal of such a philosophical system was always an object of criticism for Wittgenstein even at the time of the Tractatus, but more explicitly so, and for different though related reasons, in his later writings. And on the other hand it would be quite absurd to deny that the philosophy of, say, Philosophical Investigations, is in obvious and fundamental conflict with that of the Tractatus. Indeed, the earlier sections at least of Philosophical Investigations are an explicit criticism of the point of view underlying the earlier work. Moreover, progressively as its argument develops, it concerns itself in more and more detail with topics in epistemology and the philosophy of mind which are either not dealt with at all in the Tractatus or at most receive passing mention there.

But if we are impressed by this last fact in the wrong way, we are in great danger of not seeing the wood for the trees. Many contemporary philosophers, I think, implicitly accept Russells view that Wittgenstein just abandoned his early interest in the nature of logic to concentrate on (what Russell held to be) the easier task of describing the use of certain expressions in ordinary language.questions as the nature of Freuds contribution to psychology and of Frazers social anthropology.

Let me first try to sketch how these problems about logic, language and reality presented themselves to Wittgenstein in the Tractatus, problems dealt with in the contributions by Miss Ishiguro, Mr. Rhees and Professor Shwayder. They are all contained in the central question, What is a proposition?, a question which is discussed in the light of a number of particular puzzles, some of the more important of which are as follows. There is, first, a puzzle about the relation which holds between a proposition and a fact in virtue of which we say that a proposition states a fact. What makes this perplexing is that a proposition does not have to be true in order to be meaningful. A proposition must already stand in a relation to reality if it means something (i.e. if it really is a proposition at all); to understand the proposition is to know what fact it states to obtainand the question whether that fact really does obtain is a further one. Because a proposition may be false, its meaningfulness cannot consist in any relation in which it stands to an actually obtaining fact (at least not the fact that it states to obtainfor perhaps there is no such fact). If one then tries to say that the meaning of a false proposition consists in its relation to the fact stated by its negation, one is then confronted with the hardly less perplexing problem of the nature of negative propositions: do these state negative facts? And what are these supposed to be, given that the world is everything that

Next page