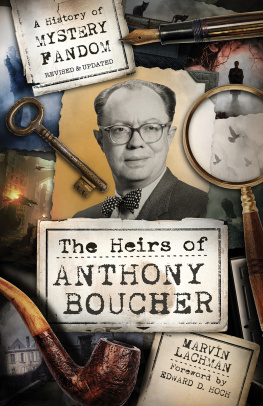

Also by Marvin Lachman

Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection (with co-authors Chris Steinbrunner, Otto Penzler, and Charles Shibuk)

A Readers Guide to the American Novel of Detection

The American Regional Mystery

Detectionary (with co-authors Chris Steinbrunner, Ottor Penzler, Charles Shibuk, and Francis M. Nevins)

The Villainous Stage

Copyright 2005, 2019 by Marvin Lachman

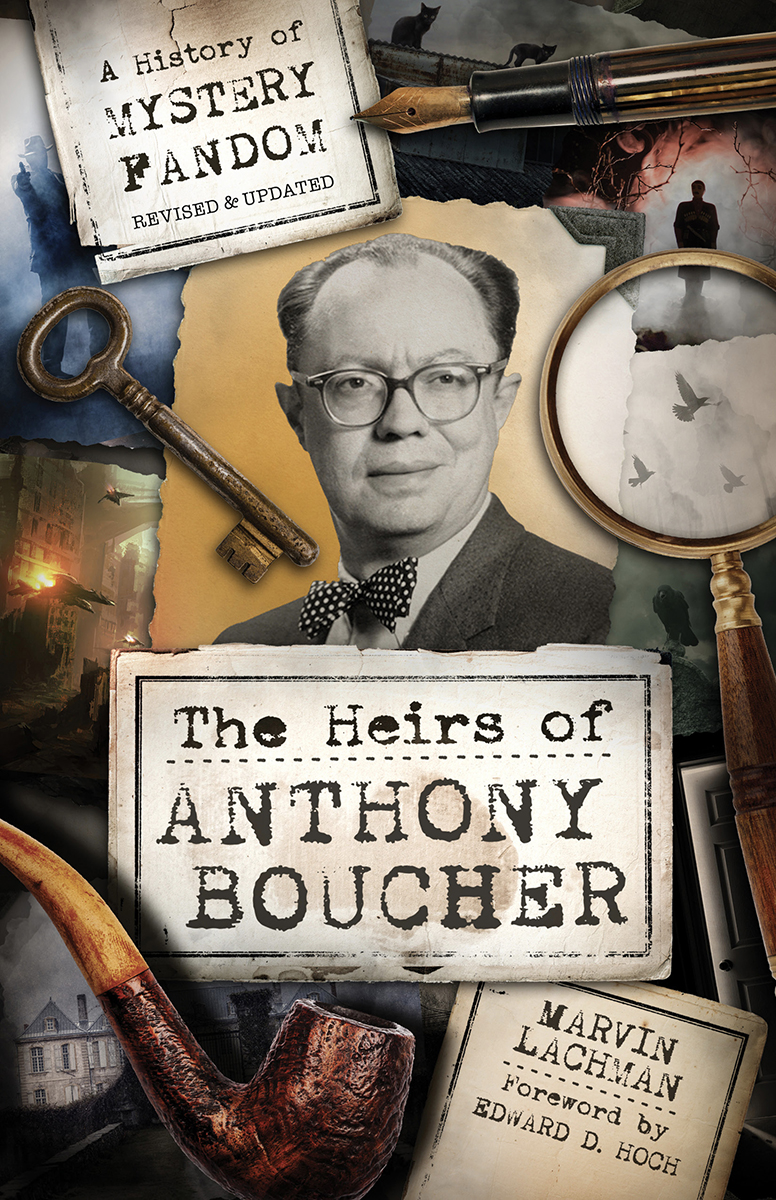

Cover and internal design 2019 by Sourcebooks

Cover design by The Book Designers

Cover images lekseykolotvin/Shutterstock, andreiuc88/Shutterstock, Arcady/Shutterstock, AWP76/Shutterstock, Dark Moon Pictures/Shutterstock, Gavran333/Shutterstock, Hitdelight/Shutterstock, Irina Kozorog/Shutterstock, LiliGraphie/Shutterstock, Liu zishan/Shutterstock, Maria Isaeva/Shutterstock, Nejron Photo/Shutterstock, Stephen Coburn/Shutterstock, Stocksnapper/Shutterstock, Taigi/Shutterstock, zef art/Shutterstock

All internal photographs Art Scott, unless otherwise noted

Sourcebooks, Poisoned Pen Press, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Contents

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Allen J. Hubin. He was the first great heir of Anthony Boucher. When he founded The Armchair Detective ( TAD ) in 1967, it gave the fans of crime fiction a publication for which to write and eventually a reason to meet. For more than ten years he published and edited The Armchair Detective , which set a standard of excellence by which later fan journals would be judged. It published articles, check lists, reviews, and letters that often sparked controversy and provided humor.

For three years Hubin replaced Boucher as mystery reviewer for the New York Times Book Review. He also replaced Boucher as the editor of the annual volume Best Detective Stories of the Year from 1970 through 1975. Meanwhile, Hubin had a full-time job as a research chemist, a family (wife and five children), and the magazine to edit and publish. Even after he was no longer publishing The Armchair Detective, Hubin continued as an unpaid reviewer for it, and The Mystery FANcier , The Mystery * File , and Deadly Pleasures .

It was while publishing TAD that Hubin began the project that may well place him above all other fans: The Bibliography of Crime Fiction, 17491975. This listing of virtually every book published in our field is arguably the most indispensable reference work ever in crime fiction. Hubin updated it through 2000 via the internet and CD-ROMs. To this very day, he continues to add new titles, and dates of birth and death of mystery writers as they are discovered. Hubin expanded his bibliography to include thousands of films based on crime fiction as well as the titles of short stories in collections.

The Armchair Detective gave fans a place to meet in writing. Soon, there were small, intimate parties (in apartments such as mine). Eventually, there was Bouchercon, the World Mystery Convention, with up to 2,000 fans attending, and other conventions.

Mystery fandom as we know it today would eventually have come about without Al Hubin, but it would have been later, less scholarly, and not as much fun.

Photo by Jennifer Hubin

Allen J. Hubin

Preface

All knowledge is contained in fandom.

Anthony Boucher

This history of mystery fandom is called The Heirs of Anthony Boucher because it was to Boucher that fans turned before The Fan Revolution was launched in 1967. There were fans before 1967, and I shall discuss them. However, it was in 1967 that the mystery developed a fandom that was not limited to specific authors or characters such as Sherlock Holmes.

Boucher was an excellent mystery writer, but he gave up writing novelsthough he continued to write the occasional short storyto review mysteries for the San Francisco Chronicle in 1942. In 1951 he became the mystery critic for the New York Times Book Review. In addition, he reviewed for Ellery Queens Mystery Magazine. He was considered the outstanding reviewer of crime fiction in America and on three occasions received Edgars from Mystery Writers of America for his writing.

Boucher mentioned fan activities in his column, but there were few except for those involving Sherlock Holmes. Boucher reviewed what was perhaps the earliest general fan scholarship, A Preliminary Check List of the Detective Novel and Its Variants (1966), an annotated list of recommendations by Charles Shibuk. In 1966 Boucher also wrote of a bibliography of the works of John Dickson Carr, compiled by Rick Sneary of California.

I had been reading mysteries for almost twenty-five years before I had the opportunity to write or speak to another fan. In 1967 I was only one of millions of mystery readers, but I also considered myself a fan. I kept notes on the books I read, prepared checklists of favorite authors, and compiled brief biographies of them and their series detectives. They were only for my own use then.

My isolation was ended in 1967 when Allen J. Hubin surveyed the people who had requested Snearys work, asking if they were interested in a journal about mystery fiction. The answers he received were positive. I was one of those replying enthusiastically. Those interested subscribed and provided enough articles and reviews to fill the first issue. The Armchair Detective and the Fan Revolution were born. In a delightful coincidence, at about the same time, Lianne Carlin founded her fan magazine, The Mystery Lovers Newsletter.

Hubin wrote to me about a mystery fan, Charles Shibuk, living, as I did then, in the Bronx, and I telephoned him. We spoke of mysteries for an hour, my first conversation with another fan, and it was the start of a long friendship.

Since I was there at the beginning and have continued to be active in fandom to the present, it would be false modesty not to mention myself in this history. I have tried to be objective, but because I care about the mystery, its past, present, and future, I do not avoid expressing opinions on possibly controversial subjects.

In 1967 Bouchers advice and strong encouragement were major factors in Hubins going ahead with The Armchair Detective. Boucher enthusiastically reviewed the first issue on December 3, 1967. He spoke for mystery fans when he described it as the kind of journal for which he had been looking for many years. He wrote letters that were published in the second and third issues of The Armchair Detective.

We expected Boucher would play a major role in the newly born fandom, but that was not to be. I can still recall the shock of reading Bouchers obituary in the newspaper on May 1, 1968. It was as if a friend had died. I had read his column on Sundays for almost twenty years. Everything that has been done in mystery fandom since he died is part of Anthony Bouchers legacy.