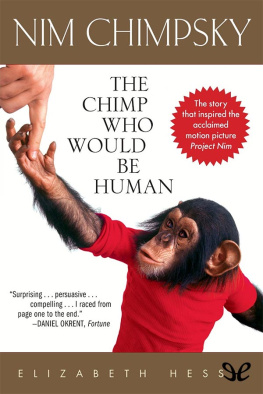

Nim Chimpsky

Contents

PART ONE

Project Nim: New York City

PART TWO

The Institute for Primate Studies:

Norman, Oklahoma

PART THREE

Sanctuary: Murchison, Texas

For Nim, Pete, Kat,

and the other beasts in my life

what is most unexpected is language

the way it threads us through and through

we the knots tied in the net

our lives the fish we catch in it

W.E.R. LaFarge

(how we are connected)

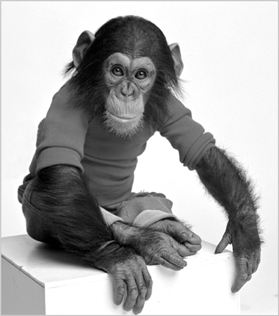

Nim Chimpsky

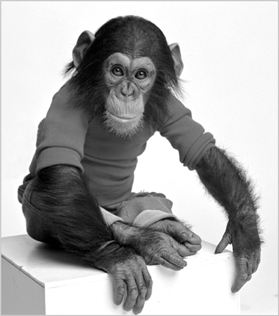

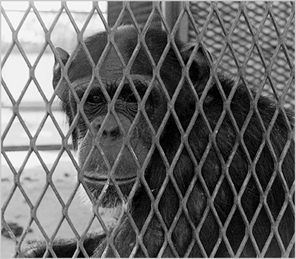

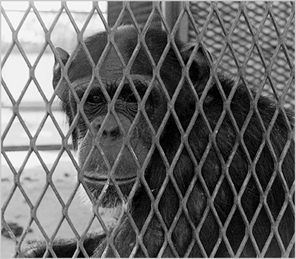

Nim's mother, Carolyn, in Norman, Oklahoma

Prologue:

The Unexpected Birth of Nim Chimpsky

NOVEMBER 19, 1973, BEGAN like any other day at the Institute for Primate Studies (IPS) in Norman, Oklahoma. There, on the outskirts of town, where suburbia fades into rolling farmland, a motley group of forty chimpanzees hooted and shrieked in anticipation of their breakfast. Emily Sue Savage (now known as Sue Savage-Rumbaugh), a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma and a regular visitor to the chimp houses at IPS, no longer cringed at the sound of this earsplitting racket. Savage spent most of her days at this research facility, collecting data for her forthcoming dissertation on mother-infant behavior in captive chimpanzees.

The chimps were in two different buildings, one of which was attached almost like an in-law apartment to the house that belonged to Dr. William Burton Lemmon, Savage's mentor and the director of the Institute. This building was where Lemmon's adult chimps lived and where Savage went to observe mothers and newborns during their first few weeks together. Most graduate students never went near the adult chimps, preferring to spend time with the much more amusing, less hostile adolescents, who were tucked away in a barn located a short distance from Lemmon's house. But Savage had chosen to study the older, bigger females. She had become inured to their odors, their aggressive gestures, and even the jets of water (or feces) they spat at her face; she understood their anxieties and appreciated their sense of humor. The budding young scientist, who would later become world famous for her groundbreaking language research with her own colony of bonobos, had clocked so many hours with these chimps that she identified more with them than with her fellow students.

That afternoon, Savage was observing Carolyn, a wild-born, eighteen-year-old female, when she saw her bend over and pull a small, dark form out of her massive body. There was no mistaking the dripping, writhing package. Trying to blend into the scene as unobtrusively as possible, Savage sat quietly and watched as Carolyn, an experienced mother, began to hug and groom her new baby, her seventh. A few critical seconds ahead of the chimps who shared quarters in the building, Savage closed one of the guillotine doors separating the cages from each other to give Carolyn some privacy and some protection from her mates. After several more minutes of focused observation, Savage went to spread the news.

Savage's teacher, the charismatic and highly unconventional William Lemmon, felt as proud of each newborn delivered by one of his chimps as if he had played a part in their creation. He rarely missed the advent of a pregnancy or, for that matter, any other development in his chimpanzee colony. But he had not known that Carolyn was pregnant, much less that she was about to give birth. She had produced six infants over the past four years (including two sets of twins) and Lemmon felt she needed a rest, so he had put her on birth control pills, the same kind that humans take, in an early experiment in primate population control. Carolyn was one of the first chimps on the pill. But apparently the pill is not foolproof for any species.

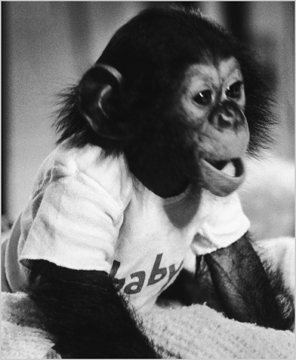

As soon as he heard the news from his student, Lemmon rushed to Carolyn's cage and found her cradling the damp, sputtering infant. This baby, as adorable as his older siblings, had protruding ears, saucer eyes the color of maple syrup, and string bean arms and legs. When he cried, Carolyn issued a rhythmic stream of whimpers that had an instant calming effect, almost like a lullaby. She ran her lips over every inch of his skin, gently kissing and grooming him from head to toe.

Grooming, an activity that cements the bond between chimp mother and child, begins at birth. In the wild, mother and child often remain together for three or four years, in constant physical contact with each other, while the youngster receives detailed instruction in the fine art of jungle survival. In captivity, the bonding process and with it the lessons passed along from one generation to the next may not remain intact; chimp mothers frequently reject their infants, refusing even to hold them after giving birth. It's as if their maternal instincts have been switched off, sometimes temporarily, sometimes forever. Like humans, chimpanzees can suffer from severe depression.

But Carolyn was an ideal mother. She held her baby close to her with one arm while she swatted away flies with her other hand. Then she leapt up onto a perch in her cage and turned her back toward her audience to face the wall, preventing Lemmon and the others in the small group that had gathered from seeing her baby. The gesture made a powerful statement, which none of them had any trouble understanding. Carolyn knew the drill. She would not have long to experience the pleasurable thrall of motherhood. This baby, like all her others, would soon be taken from her, destined for one of the research projects to which Lemmon sent most of the chimps born at IPS. As it happened, number 37, as he was listed in Lemmon's primate records, was slated for a prestigious ape language study at Columbia University, which the lead scientist had dubbed Project Nim after its research subject, who was intended to bear the name Nim Chimpsky. Carolyn's baby, known as Nim throughout his life, was taken from his mother ten days later.

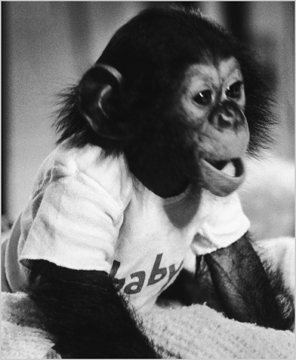

Baby Nim in New York City

Introduction:

Chimps Are Us

CHIMPANZEES WERE NEVER meant to be born, or live, in captivity. For millions of years they were safely hidden away in the African jungle, far from human eyes, where they hunted and foraged for food, fashioned crude tools out of sticks and stones, organized themselves into tight social groups that functioned like small, warring tribes, and lived by intricately structured codes of behavior that were passed down from generation to generation. In the sixteenth century, however, accounts of their existence made their way back to civilization, opening their secret world to a public fascinated by reports of exotic, human-like creatures in faraway lands. It was only a matter of time before explorers from Europe would capture some of these creatures and bring them back for display, turning them into spectacles for an awestruck audience. King Kong was just around the corner. Then as now, chimpanzees mesmerized us, precisely because of their resemblance to us.

Next page