Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Is available from the Library of Congress.

Interior design: Sarah Olson

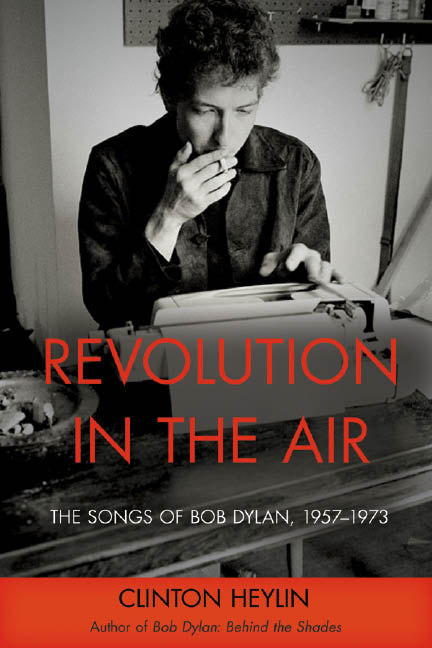

2009 by Clinton Heylin

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-55652-843-9

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To Sean Body, a gentleman-editor of the old school.

{ Contents }

1965: Bringing it All Back Home;

Highway 61 Revisited

1967: IIJohn Wesley Harding;

The Basement Tapes

19701: Self Portrait; New Morning;

Greatest Hits Vol II

19723: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid;

Planet Waves

{ Seems Like an Intro }

My songs are just me talking to myself.... [The] songs are just pictures of what Im seeingglimpses of things. Dylan to Ray Coleman, May 1965

I write all this stuff so I know what Im saying. Im behind it, so I dont feel like Im a mystery. Dylan to Lynne Allen, December 1978

Its not for me to understand my songs.... They make sense to me, but its not like I can explain them. Dylan to Denise Worrell, November 1985

People can learn everything about me through my songs, if they know where to look. They can juxtapose them with certain other songs and draw a clear picture. Dylan to Edna Gundersen, September 1990

In April 1964, on the brink of breaking through to the mainstream, Dylan told Life magazines Chris Welles, "I am my words." Coming from the man who had just written "Chimes of Freedom" and "Mr. Tambourine Man," it represented a statement of artistic intent as deliberate and self-conscious as Rimbauds "I is another." Dylan has many achievements from forty-five years in the limelight, but it is as a crafter of songson the page, in the studio, and onstagethat he is most likely to be remembered.

Yet the output of this most prodigious of song-poets remains mired in misinformation that constrains a full analysis and appreciation of his achievement. Put plainly, too many writers are starting with the whole issue of "What does it mean?" when no one has yet resolved the means by which the most remarkable artist of his era built his array of oral poetry wrapped in song. It is high time an actual order to the work was established: a context that may yet allay the catastrophe and confusion of which its practitioner remains so fond (and which he once told Ray Coleman was "the basis of [his] songs").

Even though there seems to be an unending variety of Dylan booksgood, bad, and indifferentno one has quite met the challenge of documenting every one of his songs with the aim of providing an authoritative history of the most multifaceted canon in twentieth-century popular song. To see the wood and not just the trees, we should perhaps start with a big bonfire of "books about Bob." Too many have been written by the chronically misinformed, the mercenary, and the magpie. And when the smoke begins to clear, we shall see a large stack of songs tottering in the wind, in need of shoring up with a few solid facts.

As both his output and his popularity have continued to growlest we forget, the man has recently had two transatlantic number-one albums in the space of twelve monthsthe whole thing seems to have struck others as just too damn daunting. It initially seemed that way to me. Having compiled a provisional chronological list of every known original Dylan song (excluding instrumentals), I discovered it totaled six hundred compositions. With so many songs, an ever-renewing fan base tuning in, and the ongoing pandemic of disinformation that is the Internet, a "just the facts" history of every song from composition to recording and/or performance seemed like a necessity.

Accepting that "the song is the thing" was just the first step. I was determined to organize this array of songs from Dylans pen in the order in which they were written not the order in which they were recorded or released. Only then could I start to tell the stories behind those songs not from the outer realms of speculation, but from the centrality that is their compositional history. At the end, there would hopefully be six hundred vignettes that amounted to a whole worth much more than its constituent parts. Maybe it wouldnt be the greatest story ever told, but it would provide the evidence necessary to blow away any other claimant to the singer-songwriters crown of thorns.

I should perhaps state at the outset that Revolution in the Air , despite its allusive title, is not an attempt to emulate Ian MacDonalds commendable work on The Beatles songs and their context, Revolution in the Head . Yes, it is an attempt to tell the story of an artist through his art. But in the process, I seek to show that Dylans work is a whole lot more than a series of period pieces confined to their milieu. Hence, Revolution in the Air alludes not only to one of Dylans most perfectly realized songs ("Tangled Up in Blue"), but also to something he said to journalist and author Charles Kaiser in 1985: "Ive never looked at my stuff or me as being part of a certain age or an era." The spirit underlying the best of these songs is intangible, ever moving, just out of reach. Even when one is acting as the guide.

In a (doubtless forlorn) attempt to slacken the grip of the sociologists on the study of not just Dylan, but popular literature, folk songs, and mass culture, I hope to remind readers that the songs are the product of one man from a particular time and place. He wrote the songs in a specific order, and they reflect both lesser and greater concerns. He did not write to, as it were, change the world. Even if he did. The songs repay such a forensic approach precisely because many continue to stand up, to defy the ebbing tides of trendiness that have washed away many of his peers more earnest efforts.

By sorting the historical wheat from the sociological chaff, I hope to give readers a sense of how the songs acquired the internal strength to take on a life of their own, and how their creator had the artistic will to see them through. The changes he has gone through are all here, burnished by the alchemy of song. And to feel those changes, all one really needs to do is return to the songs, hopefully with a fuller understanding as to the where, when, and why of how they came about.

Having already written extensively (exhaustively?) about the author of this inestimable body of songthough not for the past decadeI have returned to find the world of Dylan experts, would-be academics, and online know-it-alls in a greater stew than in the days when the Internet had yet to compound every crackpot theory, crank story, or distorted fact into an endemic diaspora of misinformation. Even when one so-called expert produced an encyclopedia on the man, it turned out to be an almanac of prejudices founded on precious little original research: a bringing together of mis information, not an organized compendium of facts, methodical and managed.

The question I kept asking myself was, why had no one tackled the songs in a systematic way when the likes of XTC and the Clash [!] had both been the subjects of such studies? Sure, there had been an occasional foray into the sixties catalogue, as a means to reiterate the received wisdom of others and collect a bountiful publishers advance. And there always seems to be room for another hundred-best Dylan songs piece in those periodicals that continue to feed fans of a once-fecund form.

There has even been an intelligent and genuinely original attempt to look at the early, folk-infused songs: The Formative Dylan: Transmission and Stylistic Influences, 19611963 , by the academically inclined Todd Harvey. But Harvey stops short of contemplating every song, even from the years that concern him, or putting them in the order in which they were written. So even here, I had to start again and reassemble the work, though many of the early songs put the "formulaic" in formative.

Next page