Copyright 2010 Omnibus Press

This edition 2010 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 1415 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-217-9

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web: www.omnibuspress.com

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Prologue

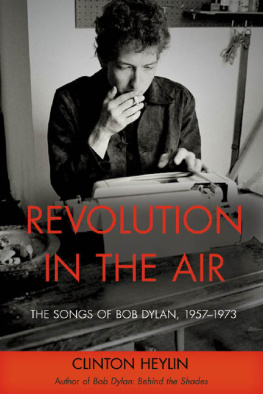

In the summer of 1969, in a small cluster of independent LA record stores, there appeared a white-labelled two-disc set housed in a plain cardboard sleeve, with just three letters hand-stamped on the cover GWW. This was Great White Wonder, a motley collection of unreleased Bob Dylan recordings, culled primarily from home sessions in Minneapolis in 1961 and Woodstock in 1967. It was the first rock bootleg, and it spawned an entire industry.

For thirty-five years now the bootleggers have persevered, even occasionally thrived. They continue to be a thorn in the side of an industry grown bloated by its own excess. Throughout these years they have reflected the best and worst of legitimate releases. The bootleggers are the ultimate free-marketeers, giving fans what they want-and to hell with the wishes of the artist or record company.

Bootleg collectors the world over will remember their initial hit that first time they stumbled upon a stall or store selling albums you werent supposed to be able to buy, and the charge that first blast of illicit vinyl gave them. For me it was as a thirteen-year-old would-be obsessive that I learnt of a seedy little porn shop in the nether regions of central Manchester, free-standing in the centre of an area modelled on Dresden circa 1945. It was a Sunday and the store was closed, but a friend and I bussed into town just to confirm that this really was a purveyor of hot wax. Sure enough, sellotaped in the window were three of their more attractive artifacts, with titles at once cryptically enticing LiveR Than Youll Ever Be, Seems Like a Freeze Out, Yellow Matter Custard huh?

Returning the following Saturday, oblivious to the well-endowed German ladies thrusting out from the covers of magazine upon magazine, I edged my way to the back of the store and two cardboard boxes. I was searching for one item in particular Bob Dylan at the Royal Albert Hall. Having read a description of the events one night in 1966 when Dylan scrambled the synapses of an entire generation, how could I fail to be intrigued?

Sorry, were out of stock on that one. Well be getting some more, though. I furtively flicked through whatever quasi-definitive Dylan bootleg guide I had along for the ride. It recommended one they did have, Talkin Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues. Great title. And I loved the lyrics Id read in Writings and Drawings. It had a proper cover, tboot. Ill take it.

Two quid, to you, lad.

My most recent legitimate acquisition-Mr Bowies Aladdin Sane-had required a seemingly hefty 2.19, courtesy of Boots the Chemists.

After all the scaremongering that accompanied bootlegs in the early Seventies (and even today), I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the sound quality of this new addition to my Dylan collection (which numbered exactly two collections of Greatest Hits) was perfectly good-a bit of hiss that was largely lost on my parents Grundig gramophone, but pretty damn fine (little did I know it was actually a Berkeley Records edition of an original Trade Mark of Quality bootleg and that TMQs version was hiss-free).

By the time I established that the acquisition of these items carried considerable kudos among the record-swapping fraternity at school, I was a teenage bootleg junkie.

In those days there was no real way of knowing what one was buying. Bootleggers were (and are, though no longer for the same reasons) notoriously vague about the sources of their material. My friendly neighbourhood bootleg dealer was generous enough to let me take items home to decide if I wanted them. Though funds were tight, I bought what I could. Soon enough he had moved to new premises and the German ladies had been shunted to the back shelf in two cardboard boxes. The albums kept multiplying. The above board record store across the road did not appreciate all the punters who came in asking if they sold bootlegs and decided to make a phone call. One Saturday I saw a new Dylan bootleg, Joaquin (pronounced walkin, as in shes a ) Antique, the first to feature outtakes from his recent return to form, Blood On The Tracks. The official album had been out all of six weeks. I was broke and prices had by now nudged up to 2.60. I was obliged to return the following weekend, money now in hand, intent on buying this exciting new platter. There was no stock. Indeed there was no window. Orbit Books was no more.

Twenty years later, Im sitting in an upmarket Chinese fry-up joint in Long Beach, Ca., trying to tape an interview with one of the central figures in the Eighties bootleg boom over a cacophony of sizzling fat. Eric Bristow-his chosen pseudonym-despite a healthy American tan, has not lost his broad Lancastrian accent. He is telling me about this great shop in Tibb Street, Manchester, where he first started buying bootlegs.

Everyones stories are different, yet the song remains the same. This book is as much an excuse to collect all those tall tales as an attempt to provide a laymans account of the contradictory constructs that have been mounted to stamp out an industry that has proved to be remarkably resilient. Bootlegs are here to stay because the appeal of hearing music that has not been authorised or sanitised by the artist will always be an enduring one.

It is, above all, a celebration. Despite many shoddy titles, shameful practices and cowboy practitioners who have been responsible for much that is bad and ugly I believe bootlegs have been a positive influence on the music. They have reminded fans that rocknroll is about the moment, that you might have to wade through static, pops, crackles, bad nights and worse tapes to find one clear moment, but no record company can capture each and every one worth preserving; that the record companies cannot lock music up in neat little boxes and say, This is what you may listen to. Hopefully the bootleggers have also freed an awful lot of music that the artists themselves might not have.

But then, never trust the artist, trust the tale.

Clinton Heylin-June 1994 & June 2003.

Introduction

A Boot By Any Other Name

The Privateering Stroke so easily degenerates into the Piratical, and the Privateering Trade is usually carried on with an Unchristian Temper, and proves an Inlet into so much Debauchery and Iniquity.1