A young boy on the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon perches on liquor crates that were emptied so their contents could be smuggled to the United States.

To Maggie and Wes

Contents

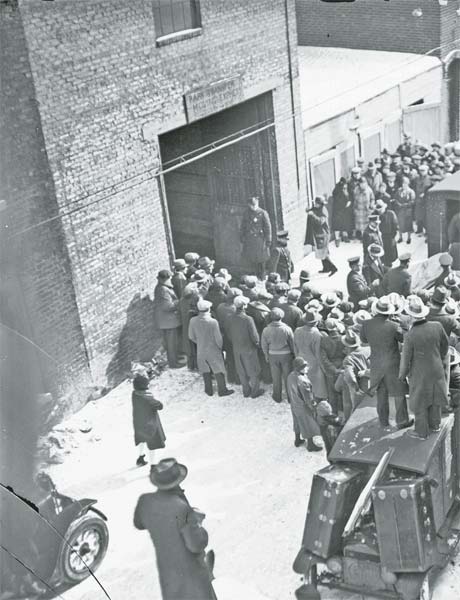

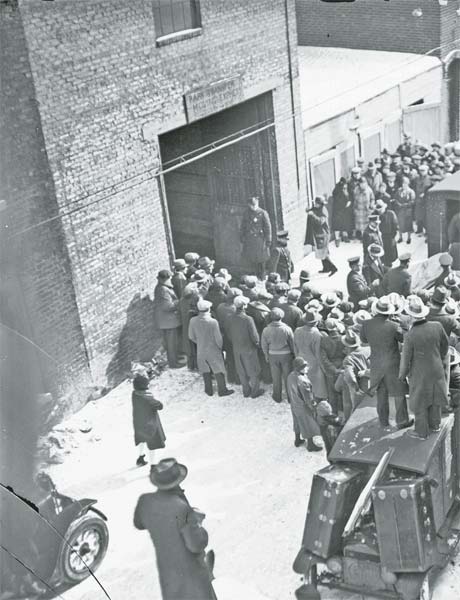

A crowd gathers outside the Clark Street garage as officials remove the victims of the St. Valentines Day murders.

Valentines Day 1929

S OMETIME AFTER 10 A.M. on this shivery-cold and windy Chicago morning, seven men gathered in a nondescript garage warehouse on Clark Street.

Most of them were wearing hats and coats against the chill of the nearly empty warehouse as they waited, maybe for a big shipment of smuggled whiskey, maybe for a special meeting. These were no Boy Scouts. All had ties to a criminal gang run by George Bugs Moran, a slow-moving, slow-thinking thug who was supposed to be on his way to the garage. Most of them had done some jail time. One, a mechanic, maintained the gangs trucks, which delivered illegal beer and liquor to Chicago bars and nightclubs, a thriving business despite laws that banned the sale of alcoholic beverages. Another owned an illegal nightclub. A third was the business manager for Moran. There was an optometrist, who just liked hanging out with the gangsters, and three muscle men, who often carried out the gangs dirty work.

On the snow-dusted street outside, a black Cadillac with a police gong, siren, and gun rackthe type usually driven by police detectivespulled up to the curb. Four or five men emerged, two dressed like police officers, and went into the warehouse. Seeing the officers and apparently thinking local cops were conducting a routine alcohol raid, the seven men inside lined up against the back wall and put their hands in the air.

They were still in that vulnerable position when two machine guns started firing.

Investigators take a look at bullet holes left behind by a machine gun in a Chicago gangland shooting in the mid-1920s.

CHICAGO POLICE had seen dozens of gangland murders as rival gangs fought over who could provide bootleg beer and liquor to the citys many neighborhoods. But they had never seen anything as gruesome as this massacre of seven men.

It wasnt supposed to be this way. Starting nearly a century before, small groups of religious and morally minded citizens had tried to solve a growing problem of drunkenness by encouraging moderation in drinking and then, later, abstinence from alcohol. The crusade had gradually gained steam and in 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had outlawed the manufacture, sale, and transportation of liquor. Prohibition, as it was called, was a grand social revolution that was supposed to forever end drunkenness, reduce crime, and make life better for Americas families.

Nine years later, the results were quite different. People who had always followed the rules now openly ignored the highest law of the land. Children helped their parents secretly concoct brews. Young people carried flasks of whiskey in their pockets to look fashionable and hung out at illegal speakeasies, drinking. Teenage boys acted as lookouts for bootleggers or drove cars and boats loaded with illegal liquor to big cities.

As alcohol was sold all around them, police officers, public officials, judges, and politicians took bribes or looked the other way. Gangsters like Bugs Moran and the notorious Al Capone divided and controlled some of the nations biggest cities, and now they seemed to murder each other at will. Rather than become more moral and upright, America, in the eyes of many, had become a lawless society.

How had such good intentions gone so terribly, terribly wrong?

Morris Sheppard rose from a child orator to become a powerful voice against liquor.

Chapter 1

The Little Sheppard

L OOKING BACK on the childhood of Morris Sheppard, you can see glimmers of a budding statesman, the kind of earnest political leader who would want to make a big difference in the world.

Born in 1875, little Morris learned poetry and literary passages before he was old enough to recognize his ABCs. As a toddler, he would stand on the counter of a local store in rural East Texas and recite verses for a stick of candy, continuing until his pockets couldnt hold another piece.

Attending schools in small Texas towns like Daingerfield, Black Jack, and Pittsburg, he studied Greek, Latin, history, and English and developed persuasive skills and an apparent flair for leadership. At 13, he shared with some other boys the story of William Tell, the legendary marksman who shot an apple off his sons head with a bow and arrow. Admiring Tells skill and bravery, but lacking the arrows, Morris and his friends decided to reenact the deedwith a gun.

We are told, reported the Pittsburg Press in 1888, that several boys stood with apples on their heads and Morris with a target rifle shot them offthat is to say, the apples, fortunately not their heads.

The boys parents were horrified when they heard about the game and put a quick end to it. Morris escaped a whipping but got a stern lecture from his father, a local judge.

When Morris finished his regular schooling at 16, he moved on to the University of Texas in Austin. Jumping into student life at the young and still-small school, he joined a fraternity, led a literary society, played the cornet and piano, and sang in the glee club. Always fond of a good joke, he got a kick out of entering the dining hall by walking on his hands. But he was best known for his preacherlike speaking skills and was selected to compete in contests and serve as a graduation speaker.

From there he went to law school, spending two years in Austin and a third at Yale University in Connecticut. Once again, he attracted attention as a star orator, winning a debating prize and speaking at the graduation ceremonies.

Somewhere between his general-store recitations and his law degree, young Morris came to a heartfelt belief: He despised liquor and the saloons that sold it. He sometimes said his feelings grew out of his grammar school science classes, where he saw vivid drawings of a drunkards stomach and read about how alcohol destroyed the human body.

He may have been influenced by the anti-liquor stance of the Methodist church, which he joined as a college student. His time at Yale also may have hardened his stance. He arrived there in debt and driven to succeed. So, he said, I cut out every item of expense that was possible and quit every practice which might be injuriousincluding tobacco, coffee, and tea. The result, he said, was so satisfactory that those items remained on the contraband list ever since.

After Yale, young Morris began practicing law in East Texas, but in 1902, his career took an unexpected turn. His father, John, who had been elected to a second term in the U.S. House of Representatives, fell ill and then passed away. Friends immediately urged Morris to run for his fathers seat.

![Scott C (Christopher) Martin - The Sage Encyclopedia of Alcohol Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. 1 [A - D]](/uploads/posts/book/102244/thumbs/scott-c-christopher-martin-the-sage.jpg)