CONTENTS

OCTOBER 24:

BLACK THURSDAY

OCTOBER 24:

SELL!

OCTOBER 24:

WHITE KNIGHTS TO THE RESCUE

OCTOBER 25:

PRESIDENT HOOVER RESPONDS

OCTOBER 26:

SOLD OUT

OCTOBER 27:

THE KING OF THE BULLS

OCTOBER 28:

A BLOODY MONDAY

OCTOBER 29:

BLACK TUESDAY

OCTOBER 30:

AFTERMATH

,

T O D AD AND P APPA, WHO TAUGHT ME ABOUT STOCKS

I NTRODUCTION

T HE YEARS AFTER the First World War were a golden age for many Americans. The 1920s didnt just sing with the rhythms of jazz, or swing with the dancing of the Charleston; they roared with the confidence and optimism of a prosperous era.

For most of the decade, jobs were plentiful and paychecks grew steadily. Mass production and innovation helped make many items widely available and affordable. Automobiles became cheaper, faster, and more comfortable. Fledgling airlines began to carry a few passengers from city to city. Electric refrigerators and washing machines freed women from some household chores. Department stores and grocery chains expanded, offering a greater selection and lower prices than neighborhood markets.

As movies talked for the first time, radio brought instant news and entertainment into living rooms, spreading the word about the many things money could buy. A new industry, advertising, advised Americans that they needed toothpaste, mouthwash, and readymade clothing.

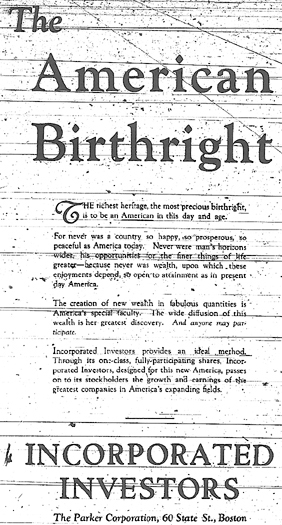

Brokerage houses advertised in newspapers and popular magazines to woo new investors. This August 1929 ad enticed readers with its claim that wealth was easily attainable for any American.

Young women, energized from winning the long fight for the right to vote, traded their heavy, long dresses for short, slim styles. They cut their hair short like the boys, and dared to wear makeup. Many women began to handle their own money.

With all the attention on buying and consumer goods, businessmen became widely admired public figures. The powerful men who ran the nations largest banks, car companies, and electric utilities became national celebrities.

Money became the sign of successthough very few people were truly wealthy. Most working Americans made just a few thousand dollars a year and worked six days a week. But those who could save some money for a down payment and spare a few dollars more from each paycheck could buy one of Henry Fords cars or a house in the suburbs on the partial-payment plan.

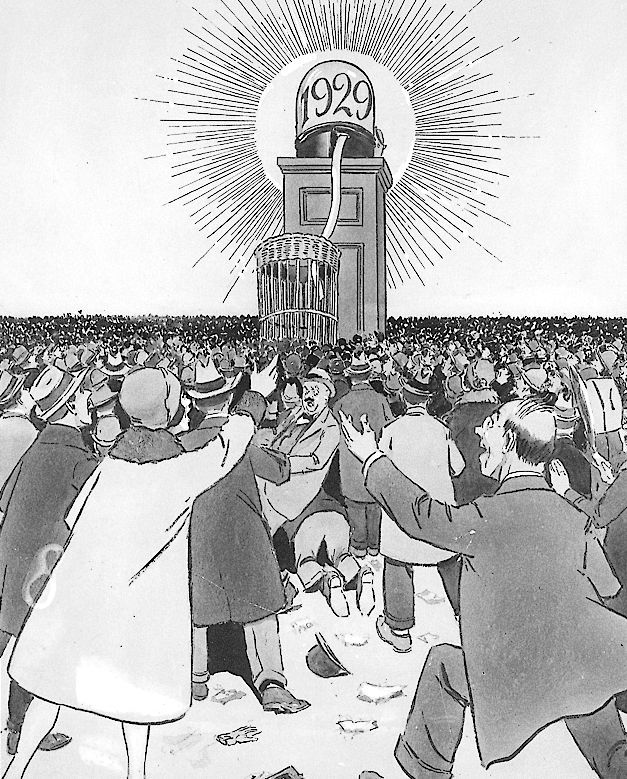

The New York Stock Exchange building, as seen by an artist in 1929. Here, at the corner of Broad and Wall streets in downtown Manhattan, was Americas financial center.

Amid all the affluence, the average man saw one way that he, too, could become rich. On Wall Street, a narrow little road in New York City, magical things were said to happen to money. Men told coworkers about it, women told their sisters, neighbors told neighbors. Those who could scrape together a few hundred dollarsor even better, a few thousand dollarscould buy stocks, pieces of paper that represented a small ownership in a company. For much of the 1920s, stocks soared in value. People clever enough to buy them could end up with more money than they ever imagined. Someone who had the foresight to buy $10,000 of General Motors stock in 1920 would have seen the investment grow to more than $1.5 million by 1929.

Unfortunately, few people had that kind of cash or insightor luck. Many investors never made money in the market, or at least not very much. And there werent all that many stock investors to start with. Out of 121 million people, probably just 1.5 million to 3 million of them owned stocksjust one or two out of every 100 Americans.

Still, as stock prices climbed higher and higher in 1928 and 1929, Americans were captivated by the idea of making money in such a fast and fantastic way. Newspapers listed daily stock prices. Radio broadcasts gave the days stock-market highlights.

The fascination with wealth drew many more people than had ever before gambled their savings in such a risky and unpredictable place as the stock market. Their zeal was supported and encouraged by some of the nations most respected leaders. As stock prices seemed to climb to the sky and beyond, these prominent men began to chase after wealth themselves. Executives who had spent their lives building solid reputations cut secret deals in pursuit of their own stock-market riches. Greed took hold.

Few seemed to care. The market was enchanted, part of an affluent and exciting time that seemed likely to continue forever. Politicians, professors, and businessmen proclaimed that this was a new era, where the old ups and downs no longer applied. Americans flourishing in the 1920s shared a feeling, said historian David M. Kennedy, that they dwelt in a land and time of special promise.

Then came October 1929.

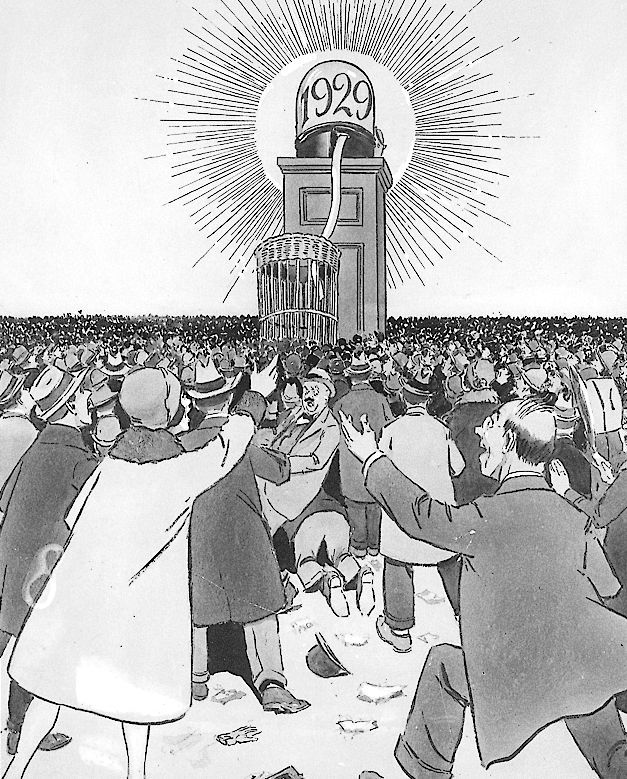

This famous January 1929 cartoon from Forbes magazine, titled The Goal, illustrates the frenzy to get rich in the stock market. Ordinary people rush toward a ticker machine that printed out the latest stock prices.

OCTOBER

24

B LACK T HURSDAY

W ORD SPREAD QUICKLY on this crisp fall morning: Stocks were in big trouble. The boys selling the morning newspapers shouted the news. Serious-voiced announcers on the radio commented on it. On the street, everyone was talking about it. Something was terribly wrong with the stock market, the greatest fountain of wealth in the history of America.

In the financial district of New York City and in other offices where brokers sold stocks, people began to gather well before stock trading formally began at 10 A.M. Men and women, nervous and pale, rushed to grab seats in the special customers rooms at brokerage houses all around Wall Street. One observer said they looked like dying men counting their own last pulse beats.

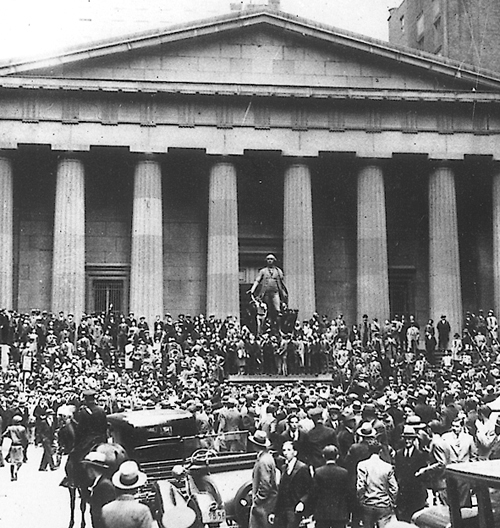

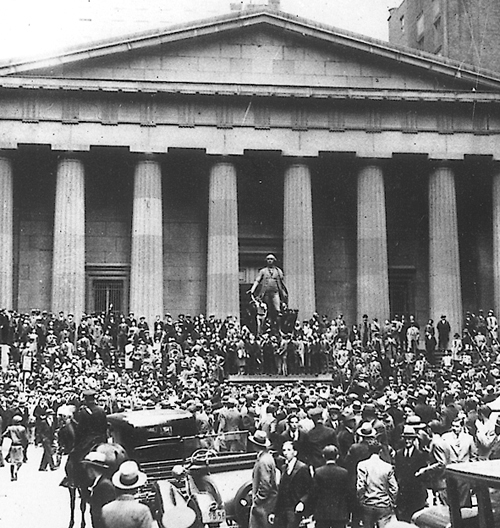

People also hurried to the corner of Broad and Wall Streets, just across the way from the New York Stock Exchange. Hundreds, then thousands, filled the streets and sidewalks. Men in overcoats and fedoras and women on break from their stenographers jobs crowded in front of J. P. Morgan & Company, the powerful banking company at 23 Wall Street. They lined the stairs of the Subtreasury Building, right near the statue marking where George Washington was sworn in as the nations first president. Usually, this kind of massive crowd gathered only for fires or to peer at the gore of some new crime. This day, though, there was nothing to see.

These men and women packed the street and steps around a statue of George Washington because it was the best place to pick up any tidbits about what was happening inside the Exchange.

Fear and excitement had brought them, the kind of intense, heart-pounding emotion felt when something really bad is happening. If stocks were dropping, plans for the future were disappearing too. For some people gathered there, every cent they owned was riding on stocks, those odd pieces of paper that represented small stakes in American companies. For others, the stock markets climb had simply been an amazing thing to watch.