Longitude

The Illustrated Longitude

(with William J. H. Andrewes)

Galileos Daughter

The Planets

Letters to Father (translated and annotated)

A More PERFECT HEAVEN

How Copernicus Revolutionized the Cosmos

DAVA SOBEL

To my fair nieces,

AMANDA SOBEL

and

CHIARA PEACOCK,

with love in the Copernican

tradition of nepotism.

Contents

Chapter 1

Moral, Rustic, and Amorous Epistles

Chapter 2

The Brief Sketch

Chapter 3

Leases of Abandoned Farmsteads

Chapter 4

On the Method of Minting Money

Chapter 5

The Letter Against Werner

Chapter 6

The Bread Tariff

Chapter 7

The First Account

Chapter 8

On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

Chapter 9

The Basel Edition

Chapter 10

Epitome of Copernican Astronomy

Chapter 11

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief Systems of the World, Ptolemaic and Copernican

Chapter 12

An Annotated Census of Copernicus De Revolutionibus

To the Reader, Concerning

This Work

Since 1973, when the five hundredth anniversary of his birth brought his unique story to my attention, I have wanted to dramatize the unlikely meeting between Nicolaus Copernicus and the uninvited visitor who convinced him to publish his crazy idea.

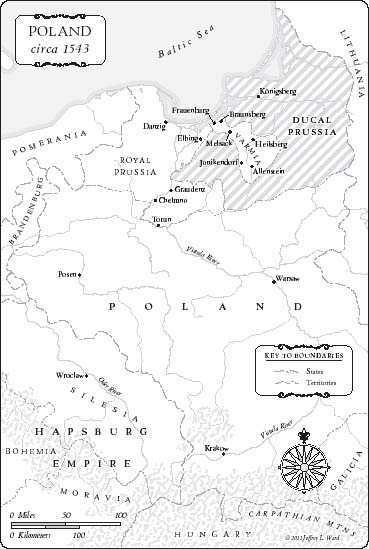

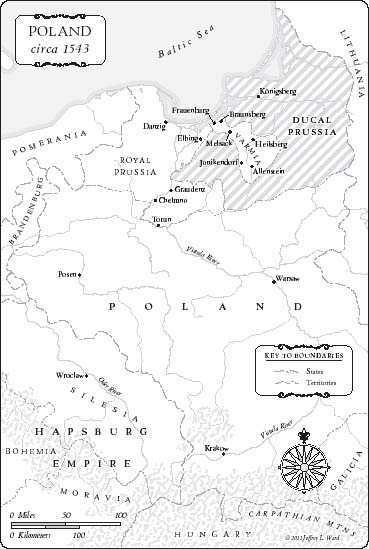

Around the year 1510, near the age of forty, Copernicus reenvisioned the cosmos with the Sun, rather than the Earth, at its hub. Then he concealed the theory for thirty years, fearful of ridicule from his mathematician peers. But when his unexpected guest, called Rheticus, made the dangerous, several-hundred-mile journey to northern Poland in 1539, eager to learn the novel planetary order from its source, the aging Copernicus agreed to end his silence. The youth stayed on for two years, despite laws barring his presence, as a Lutheran, from Copernicuss Catholic diocese during this contentious phase of the Protestant Reformation. Rheticus helped his mentor prepare the long-neglected manuscript for publication, and later hand-carried it to Nuremberg, to the best printer of scientific texts in Europe.

No one knows what Rheticus said to change Copernicuss mind about going public. Their dialogue in the two-act play that begins on perceptive editor, George Gibson, for urging me to plant it in the broad context of history by surrounding the imagined scenes with a fully documented factual narrative that tells Copernicuss life story and traces the impact of his seminal book, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, to the present day.

Part One

Prelude

Bless the Lord, O my soul.

Who layeth the beams of his chambers in the waters: who maketh the clouds his chariot: who walketh upon the wings of the wind.

Who laid the foundations of the Earth, that it should not be removed for ever.

PSALM 104:1, 3, 5

The great merit of Copernicus, and the basis of his claim to the discovery in question, is that he was not satisfied with a mere statement of his views, but devoted a large part of the labor of a life to their demonstration, and thus placed them in such a light as to render their ultimate acceptance inevitable.

FROM Popular Astronomy (1878),

BY SIMON NEWCOMB, FOUNDING PRESIDENT OF

THE AMERICAN ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY

Chapter 1

Moral, Rustic, and Amorous Epistles

FROM Letters of Theophylactus Simocatta,

THE FIRST PUBLISHED WORK BY COPERNICUS, 1509

Nicolaus Copernicus, the man credited with turning our perception of the cosmos inside out, was born in the city of Torun, part of Old Prussia in the Kingdom of Poland, at 4:48 on Friday afternoon, the nineteenth of February, 1473. His horoscope for that auspicious moment (preserved in the Bavarian State Library in Munich) shows the Sun at 11 of Pisces in the sixth house, while Jupiter and the Moon are conjunct, or practically on top of one another, at 4 and 5, respectively, of Sagittarius, in the third house. Whatever clues to character or destiny such data may contain, this particular natal chart is an after-the-fact construct, created at the end of the astronomers life and not the beginning of it (with the time of birth calculated, as opposed to copied from a birth certificate). At the time his horoscope was cast, Copernicuss contemporaries already knew he had fathered an alternate universethat he had defied common sense and received wisdom to place the Sun at the center of the heavens, then set the Earth in motion around it.

Nearing seventy, Copernicus had little cause to recall the exact date of his birth, let alone the hour of it down to the precision of minutes. Nor had he ever expressed the slightest faith in any astrological prognostications. His companion at the time, however, a professed devotee of the juridical art, apparently pressed Copernicus for biographical details to see how his stars aligned.

The horoscopes symbols and triangular compartments position the Sun, Moon, and planets above or below the horizon, along the zodiacthe ring of constellations through which they appear to wander. The numerical notations describe more precisely where they lie at the moment, with respect to the twelve signs and also twelve so-called houses governing realms of life experience. Although the diagram invites interpretation, no accompanying conjecture has survived alongside it. One modern astrologer, invited to consider Copernicuss case, used computer software to draw a new configuration in the shape of a wheel, and added solar-system bodies unknown in his time. Uranus and Neptune thus crept into the third house beside the Moon and Jupiter, while Pluto, a dark force, manifested itself opposite the Sun, at 16 of Virgo in the first house. The Pluto-Sun opposition drew a gasp from the astrologer, who declared it the hallmark of a born revolutionary.

The bold plan for astronomical reform that Copernicus conceived and then nurtured over decades in his spare time struck him as the blueprint for the . Even so, he proceeded cautiously, first leaking the idea to a few fellow mathematicians, never trying to proselytize. All the while real and bloody revolutionsthe Protestant Reformation, the Peasant Rebellion, warfare with the Teutonic Knights and the Ottoman Turkschurned around him. He held off publishing his theory for so long that when his great book, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, finally appeared in print, its author breathed his last. He never heard any of the criticism, or acclaim, that attended On the Revolutions. Decades after his death, when the first telescopic discoveries lent credence to his intuitions, the Holy Office of the Inquisition condemned his efforts. In 1616,