BY THE SAME AUTHOR A More Perfect HeavenLongitudeThe Illustrated Longitude (with William J. H. Andrews) Galileos DaughterThe PlanetsLetters to Father (translated and annotated)

Contents

Many moments in the life of the great astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, born Niklas Koppernigk in Torun, Poland, in 1473, lend themselves to dramabeginning with the early deaths of his parents, which left him an orphan by age ten. Later the deus-ex-machina intervention of his powerful uncle, a bishop of the Catholic Church, sent him far south to the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, then over the Alps to study law at Bologna, and finally to Padua, where he studied medicine so he could serve as the bishops personal physician. When he became a churchman himselfa canon of the cathedral at Frauenburg, the City of Our Ladyhe undertook arduous and dangerous missions to patrol the landholdings of his diocese. More than once he defended an episcopal palace from marauding bands of Teutonic Knights.

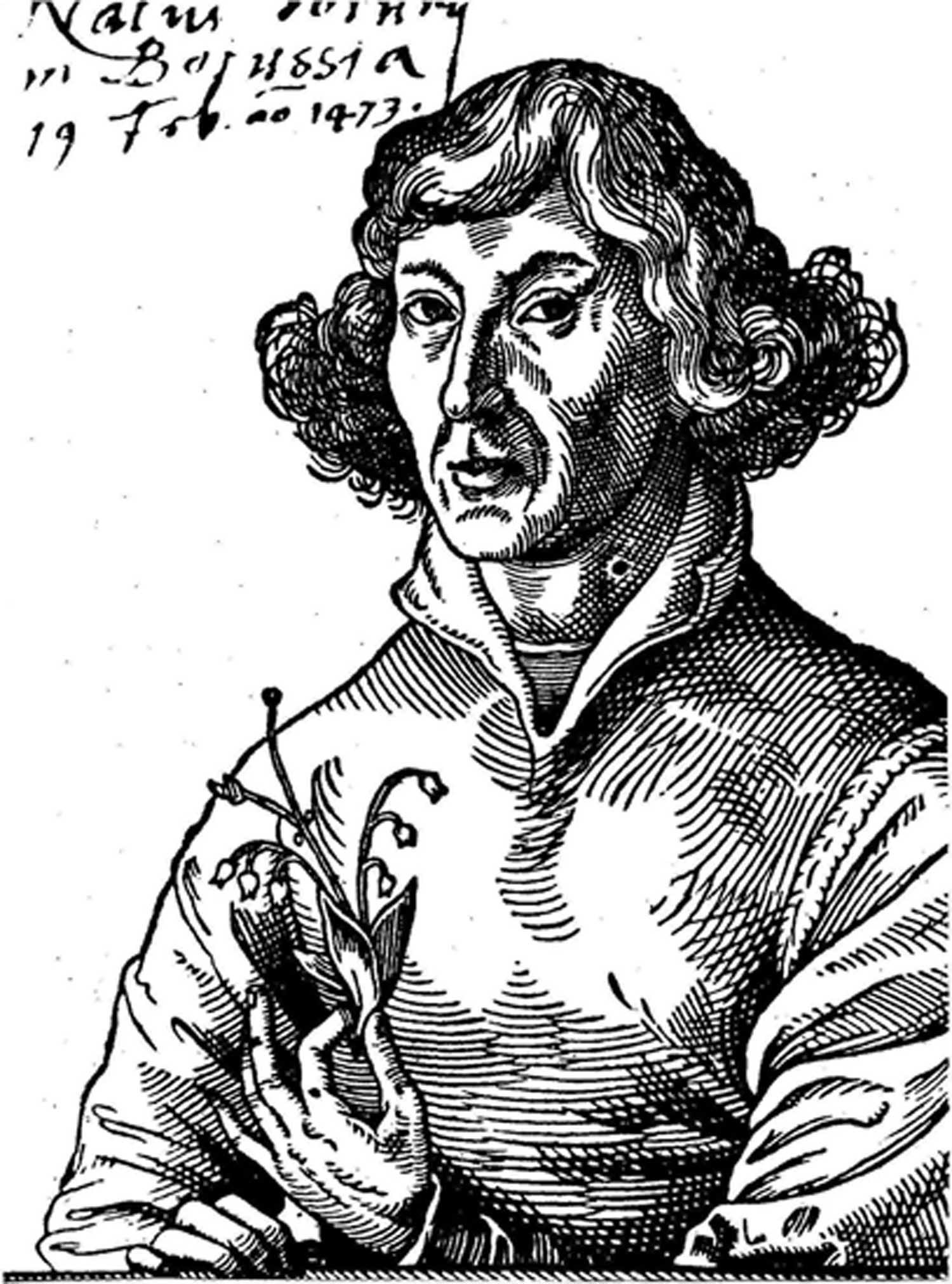

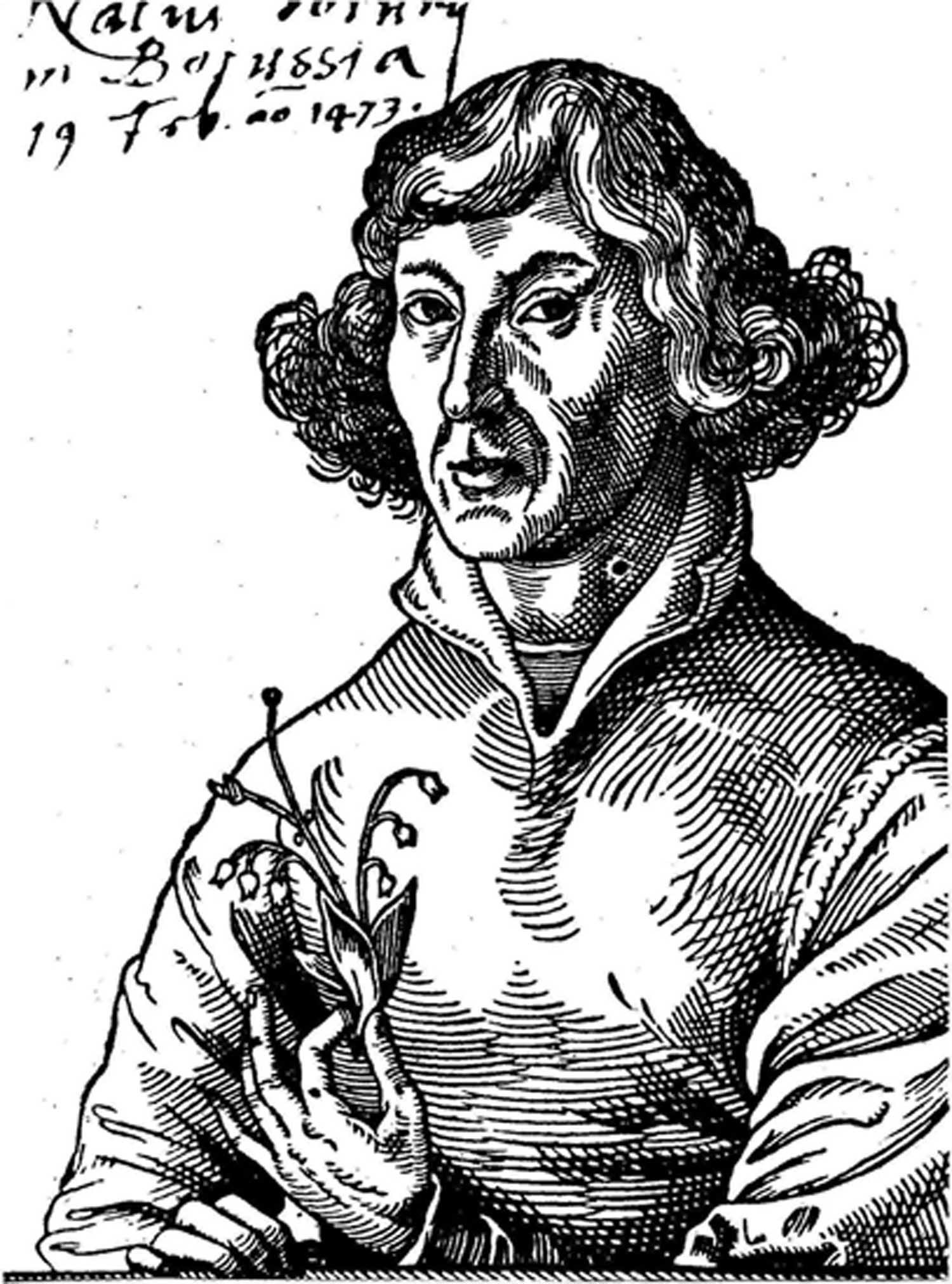

In 1522, he headed off a financial crisis by advising the Polish king on how to reform the currency. Surely one of the most dramatic moments by his own reckoning occurred sometime before 1510, when a phenomenal stroke of insight convinced him that the Sun, and not the Earth, stood at the center of the heavens. Although Copernicus wrote copiously about his heliocentric theory, he never described the events or thoughts that led him to his stunning conclusions: The Earth moves. It rotates daily on an axis and travels yearly around the Sun, among the other planets.  Copernicus holds a lily of the valley, an early Renaissance symbol of a medical doctor (probably because of the flowers association with the god Mercury, whose snake-entwined caduceus promoted healing), in this wood-block portrait by Tobias Stimmer. The rapidity of these presumed movements required a leap of faith, for Copernicuss Earth did not merely turn; it spun at a thousand miles an hour, and hurtled through its orbit at many times that rate. Such concepts seemed so foolish, so unlikely, so counterintuitive, that Copernicus feared ridicule for even proposing them.

Copernicus holds a lily of the valley, an early Renaissance symbol of a medical doctor (probably because of the flowers association with the god Mercury, whose snake-entwined caduceus promoted healing), in this wood-block portrait by Tobias Stimmer. The rapidity of these presumed movements required a leap of faith, for Copernicuss Earth did not merely turn; it spun at a thousand miles an hour, and hurtled through its orbit at many times that rate. Such concepts seemed so foolish, so unlikely, so counterintuitive, that Copernicus feared ridicule for even proposing them.

Worse, he dreaded being branded as irreverent for upholding notions at odds with numerous passages of Holy Writ. Nevertheless the idea took hold of him, because only the motion of the Earth could account for the wanderings and relative positions of the other planets. He devoted three decades to the explication of his theory in a lengthy treatise, now known as On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres. It was a big bookapproximately four hundred folio pages in Copernicuss small, neat handdense throughout with mathematical jargon, charts, tables, and geometrical diagrams. He made no effort to publish the manuscript, apparently lacking the courage to do so. Copernicuss indecision grew into a true dilemma upon the arrival in 1539 of an uninvited visitor.

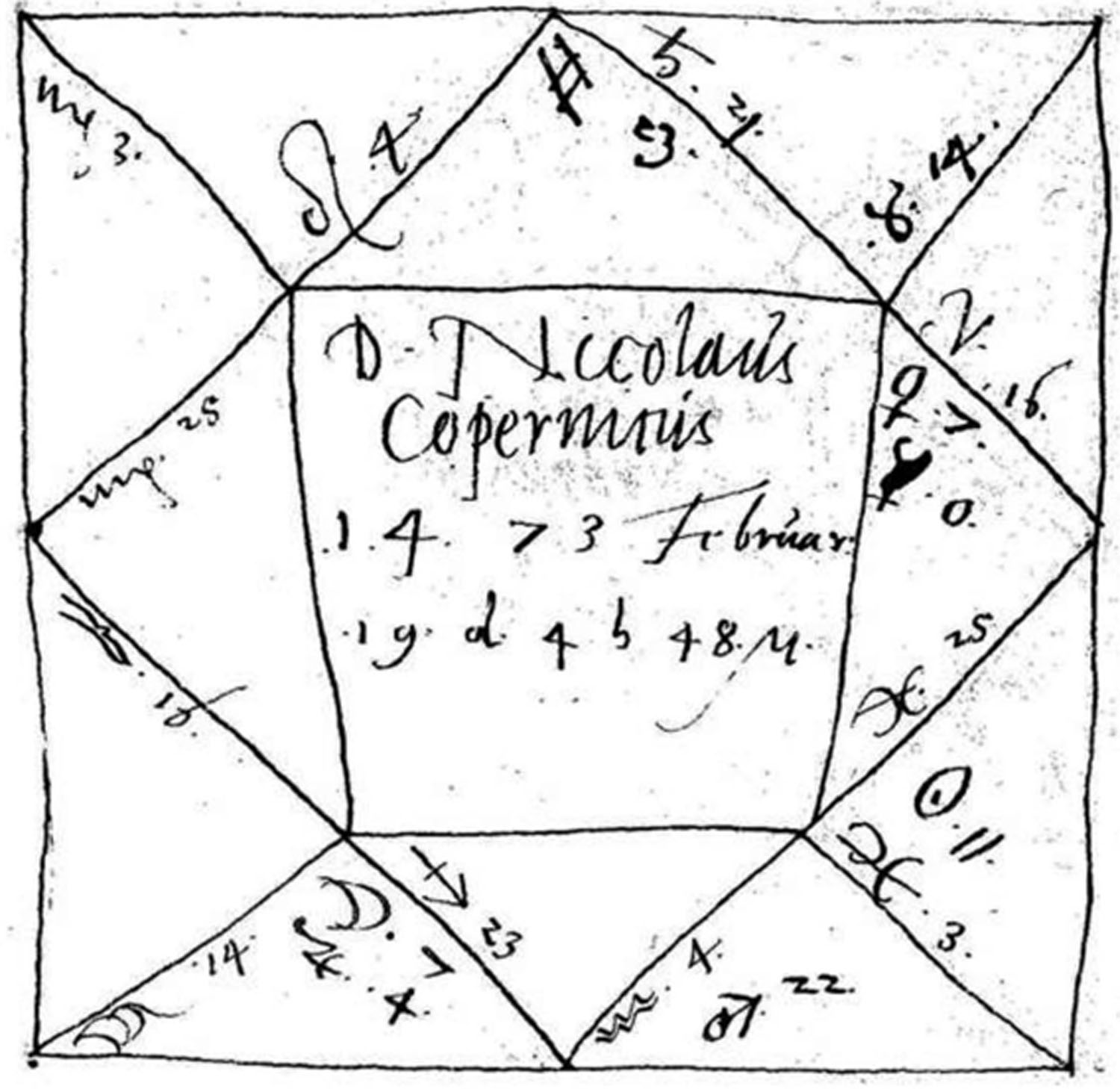

Georg Joachim Rheticus, a twenty-five-year-old mathematical prodigy from Martin Luthers Wittenberg, traveled more than five hundred miles to the northern Polish province of Varmia to seek out the aging Copernicus. His timing was terrible. The bishop of Varmia had recently passed a law banishing all Lutherans from the diocese. This same bishop (a successor to Copernicuss uncle) further tested his powers by threatening to deprive some of Copernicuss fellow canons of their sinecures, and also by pressuring Copernicus to drive away his loyal female housekeeper. The last thing Copernicus could reasonably do in this uneasy climate was to harbor a heretic.  HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS

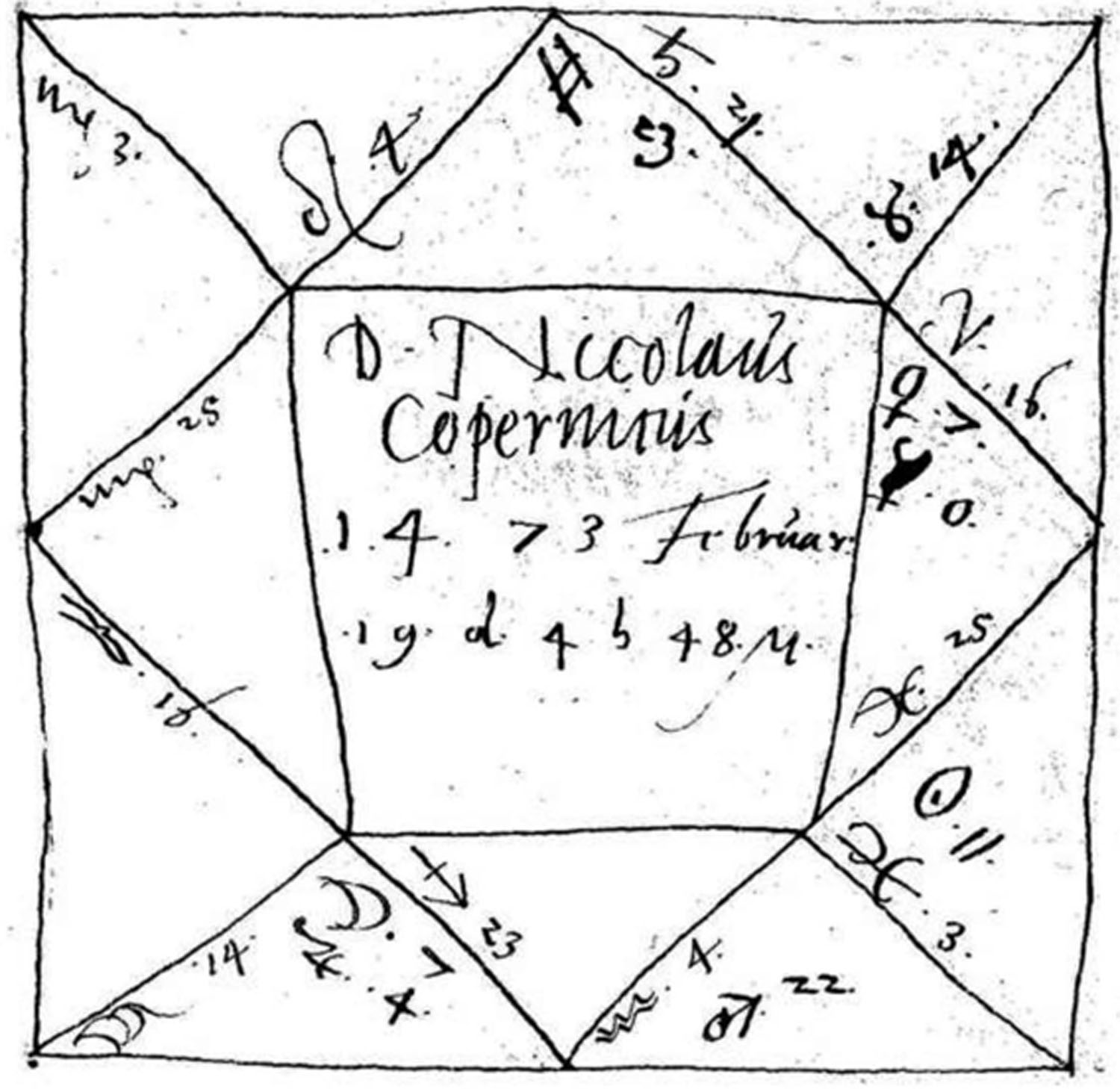

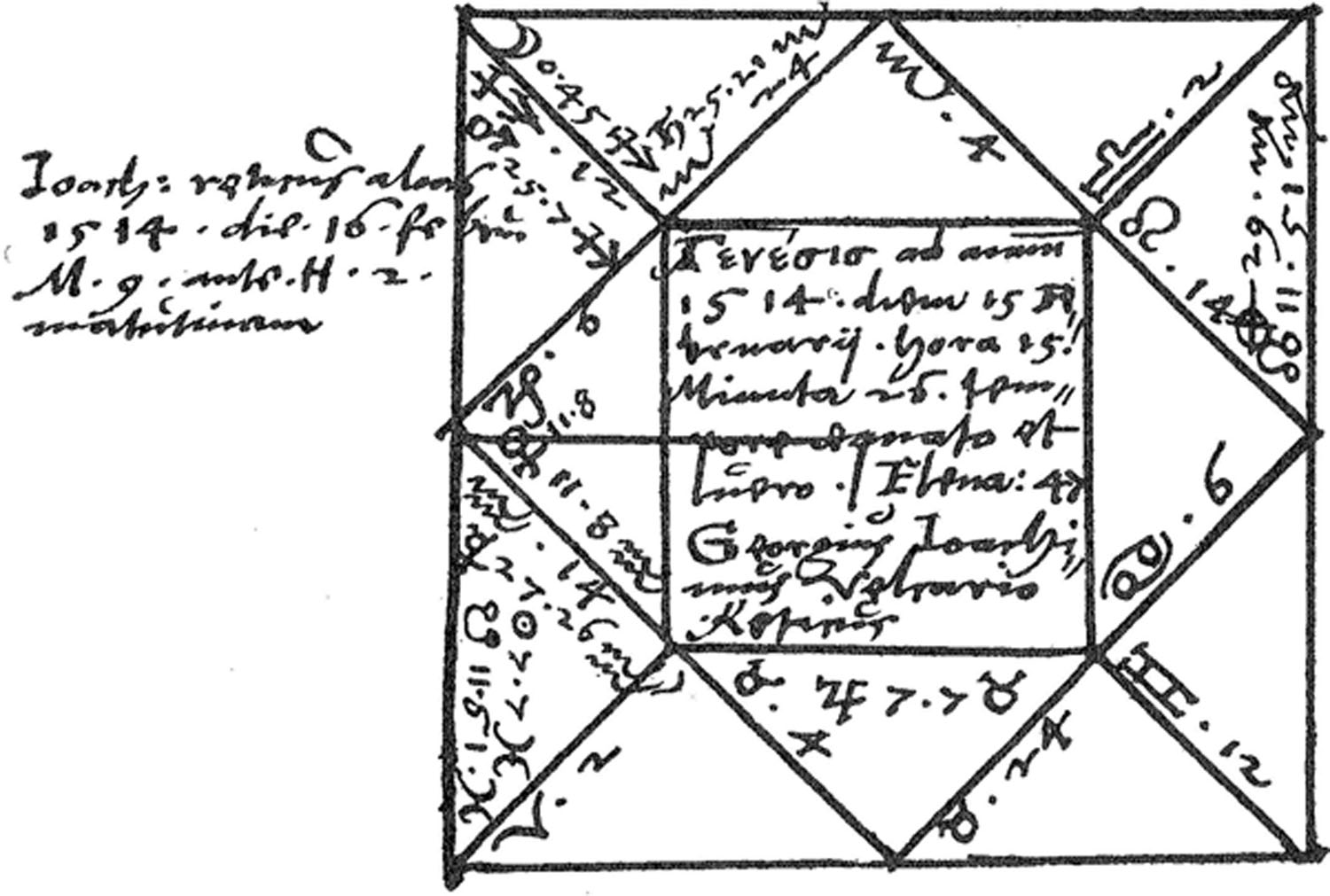

HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS

Astronomers and astrologers in Copernicuss time shared the same pool of information about the positions of the heavenly bodies against the backdrop of the stars.  HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS

HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS

Astronomers and astrologers in Copernicuss time shared the same pool of information about the positions of the heavenly bodies against the backdrop of the stars.

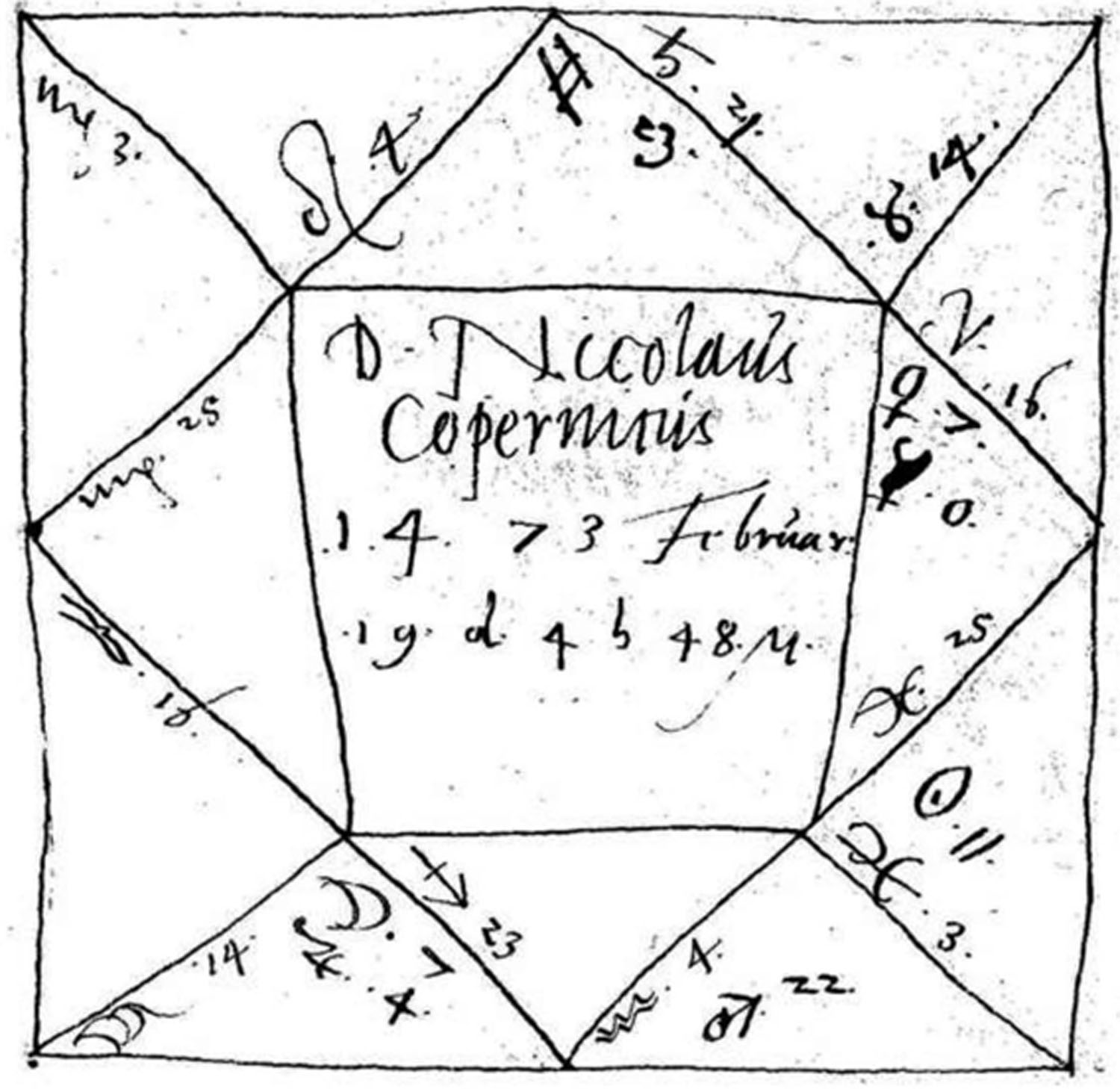

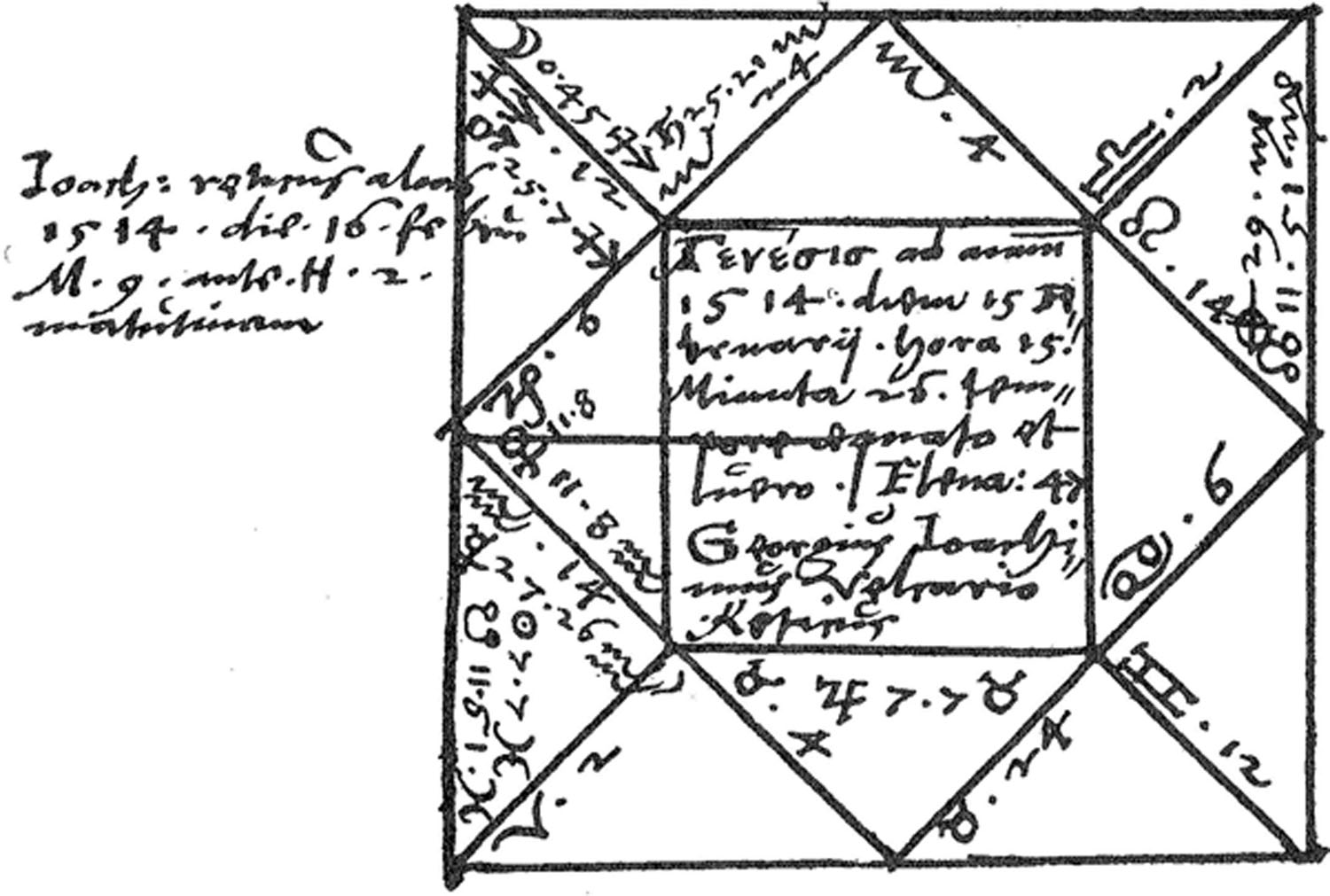

Until the invention of the telescope in the seventeenth century, position finding and position predicting constituted the entirety of planetary scienceand the basis for casting horoscopes. NATAL CHART FOR RHETICUS

NATAL CHART FOR RHETICUS

The dire prospects suggested in this horoscope for Georg Joachim Rheticus caused his student Nicholas Gugler, who drew the chart, to recalculate the professors birth time and date. The true date of February 16, written in the margin, disagrees with the more favorable date in the diagram, February 15. This is the moment I chose to dramatize in my play, And the Sun Stood Still. Rheticuss visit is a well-documented historical fact, as is his role in the ultimate publication of Copernicuss book in Nuremberg in 1543. The words that passed between them, however, went unrecorded throughout the two years of Rheticuss sojourn in Varmia. By the strength of his arguments, by the force of his personality, by becoming Copernicuss only disciple, Rheticus convinced his mentor to reverse the reticence of a lifetime. Other undocumented details in the historical record include the ploys used to hide Rheticus from the bishops spies, the nature of Copernicuss relationship with his housekeeper, Anna Schilling, and the negotiations that enabled Copernicus to dedicate his magnum opus to the reigning pope, Paul III.

All these issues, not to mention the wellspring of Copernicuss convictions, seemed open to fictional exploration. Copernicuss story first came to my attention in 1973, the five-hundreth anniversary of his birth. The February issue of Sky & Telescope featured the only known portrait of Copernicus on its cover, with a capsule biography inside by science historian Edward Rosen. That article introduced me to Rheticus and inspired me to try to write a play, though I did not attempt it right away. I took further inspiration from astronomer Owen Gingerich of Harvard, who devoted many years to locating and examining the several hundred extant copies of On the Revolutions, so as to trace the course of its influence. In 2005, the year archaeologists in Poland tore up the floor of Copernicuss cathedral in a search for his mortal remains, I began to imagine the Copernicus-Rheticus exchange.

The version of And the Sun Stood Still presented in this volume differs significantly from the one that appeared in 2011 as the centerpiece of my book A More Perfect Heaven: How Copernicus Revolutionized the Cosmos. Although the 2011 script served well to humanize its long-dead figures and demonstrate the difficulty of proving the Earths motion, it was not strong enough to stand up on stage in performance. As I continued revising the dialogue, I sought professional assistance. During a weeklong workshop experience in September 2012 with the Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company in Colorado, at the suggestion of director Stephen Weitz, I eliminated one of the six characters. This change strengthened the remaining relationships and clarified the action. And the Sun Stood Still

Next page

Copernicus holds a lily of the valley, an early Renaissance symbol of a medical doctor (probably because of the flowers association with the god Mercury, whose snake-entwined caduceus promoted healing), in this wood-block portrait by Tobias Stimmer. The rapidity of these presumed movements required a leap of faith, for Copernicuss Earth did not merely turn; it spun at a thousand miles an hour, and hurtled through its orbit at many times that rate. Such concepts seemed so foolish, so unlikely, so counterintuitive, that Copernicus feared ridicule for even proposing them.

Copernicus holds a lily of the valley, an early Renaissance symbol of a medical doctor (probably because of the flowers association with the god Mercury, whose snake-entwined caduceus promoted healing), in this wood-block portrait by Tobias Stimmer. The rapidity of these presumed movements required a leap of faith, for Copernicuss Earth did not merely turn; it spun at a thousand miles an hour, and hurtled through its orbit at many times that rate. Such concepts seemed so foolish, so unlikely, so counterintuitive, that Copernicus feared ridicule for even proposing them. HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS

HOROSCOPE FOR NICOLAUS COPERNICUS NATAL CHART FOR RHETICUS

NATAL CHART FOR RHETICUS