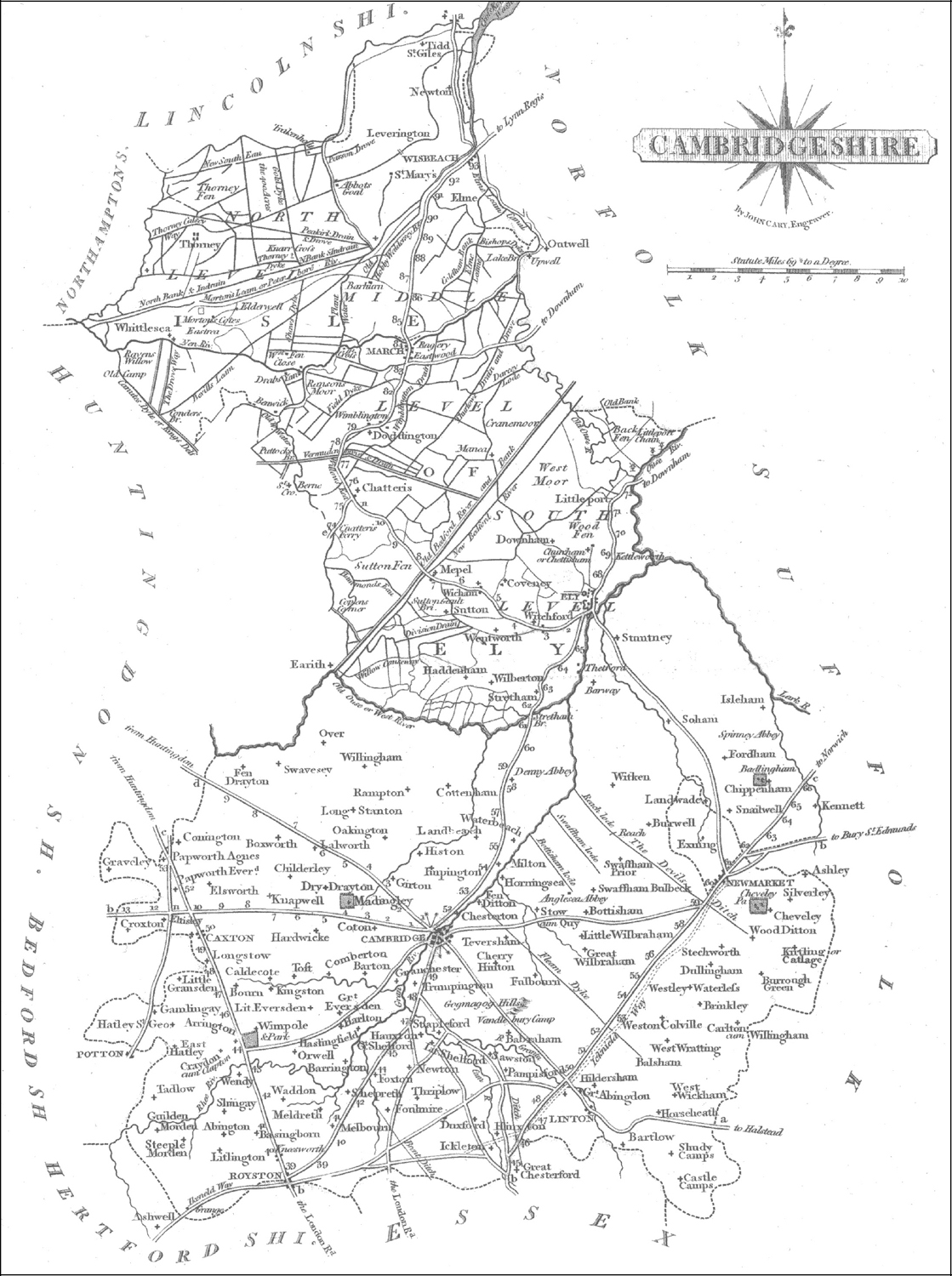

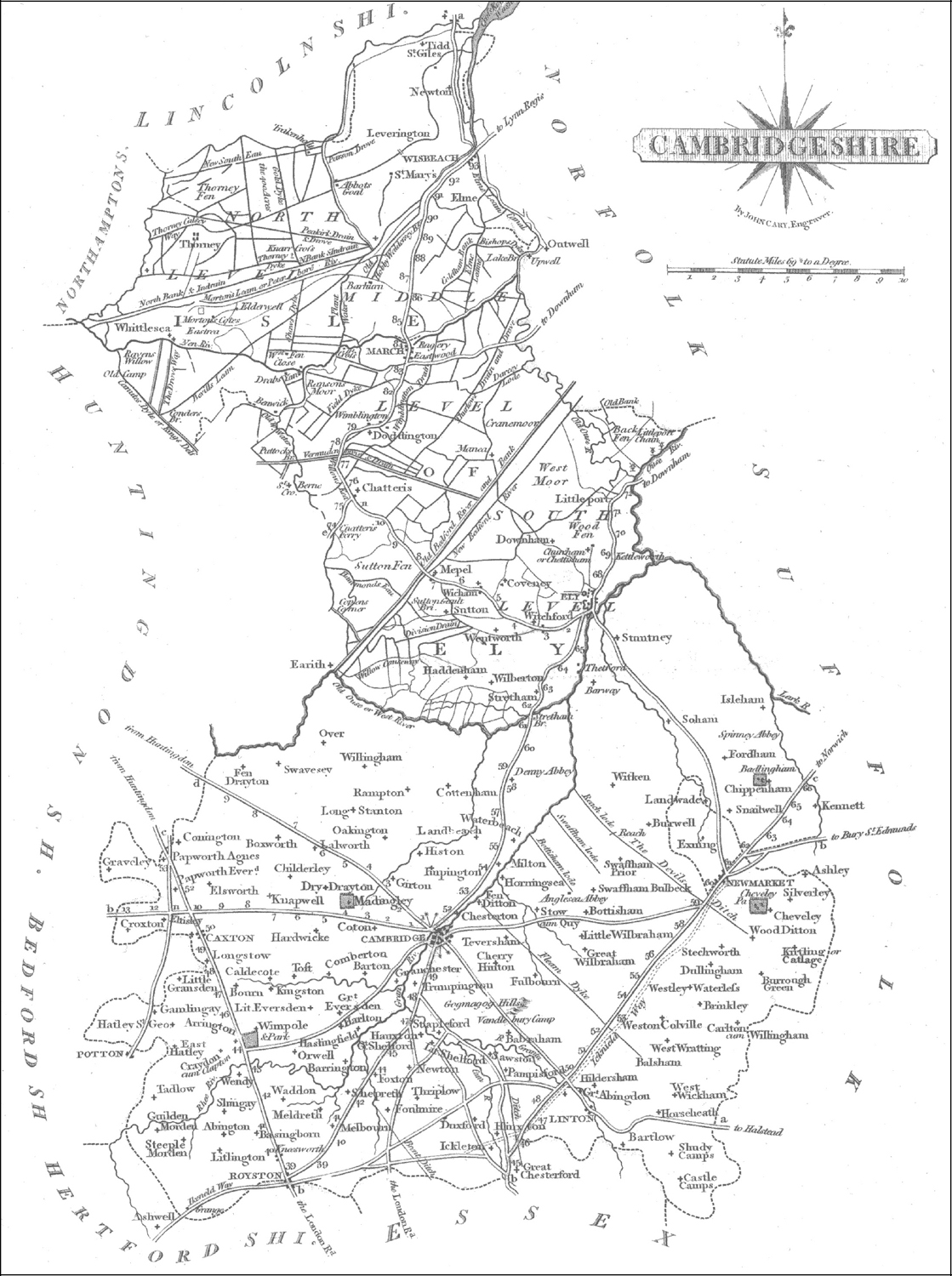

Map of Cambridgeshire, 1809 . Cambridgeshire Archives

First Published in Great Britain in 2008 by

Wharncliffe Books

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Glenda Goulden 2008

ISBN 978-1-84563-072-0

eISBN 9781783408672

The right of Glenda Goulden to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrevial system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Typeset in 10/12pt Plantin by Concept, Huddersfield.

Printed and bound in England by CPI UK.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2BR

England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

his work was made possible by the excellent research facilities available at local studies archives, libraries and museums in and around the Fens and the informed interest of their staff, most notably at Downham Market, Ely, Kings Lynn, Lincoln, Littleport, March, Northampton, Peterborough, Whittlesey and Wisbech, and at the University Library and Squire Law Library, Cambridge. Especial appreciation goes to Chris Jakes and Sue Slack of the Cambridgeshire Collection, Cambridge Central Library.

his work was made possible by the excellent research facilities available at local studies archives, libraries and museums in and around the Fens and the informed interest of their staff, most notably at Downham Market, Ely, Kings Lynn, Lincoln, Littleport, March, Northampton, Peterborough, Whittlesey and Wisbech, and at the University Library and Squire Law Library, Cambridge. Especial appreciation goes to Chris Jakes and Sue Slack of the Cambridgeshire Collection, Cambridge Central Library.

Introduction

iarist Samuel Pepys, forced into the Fens in pursuit of an inheritance in the autumn of 1663, thought the area around Wisbech a heathen place where he was bit cruelly by the gnatts. Celia Fiennes, an early travel writer riding around Britain in 1698, had even worse luck in Ely. She found it ye dirtiest place I ever saw and tho my chamber was near twenty stepps up I had froggs and slow-worms and snailes in my roome.

iarist Samuel Pepys, forced into the Fens in pursuit of an inheritance in the autumn of 1663, thought the area around Wisbech a heathen place where he was bit cruelly by the gnatts. Celia Fiennes, an early travel writer riding around Britain in 1698, had even worse luck in Ely. She found it ye dirtiest place I ever saw and tho my chamber was near twenty stepps up I had froggs and slow-worms and snailes in my roome.

The Fens were known to be unhealthy and yet, because of their uniqueness, adventurous authors were drawn there through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to make tours and travels and then to write of the foulness they had found. In 1722, with less disapproval, Daniel Defoe saw the Isle of Ely wrapped up in blankets of Michaelmas fogs with the lantern of the cathedral only now and then to be seen above, but he did call the Fens the sink of no less than thirteen counties, and listed them. One after another the curious came and had to avoyd the divellish stinging of the Gnatts which brought agues and malarial fevers. It was a brave outsider who ventured into the watery, muddy, malodorous flatness of the most unwholesome place in Britain, and yet so many did, and went on doing so. They always had.

Over the centuries, wave after wave of invaders sought the fenland waterways and the habitable islands amongst them the Romans, the Anglo Saxons, the Vikings and the Normans. They came and went. They may have attempted to make the fenlands drier in part when and where crops could be grown the land was fertile but they all left them much as they had found them.

The same higher land above the flat wet drew the monastic orders to build great abbeys and monasteries as well as many smaller religious houses. The Fens may have been, to most people, a God-forsaken wasteland, but at such as Crowland, Thorney, Ramsey, Ely and Peterborough, the religious found an isolated nearness to their God until Henry came along with his Dissolution in the 1530s.

The Fens were often a place of refuge to those who challenged authority, such as Hereward the Wake, and a challenge to be overcome by kings and would-be kings. Canute, who thought that he could command water, tried his hand in the fenlands, as did Kings John and Charles, and Oliver Cromwell.

Charles I planned to build an eminent town in the Fens, but it was destined never to be. Charlemont was to have been built at Manea, near Ely, with a canal to connect it to the Great Ouse, and he hoped to drain the wetness, joining with the Adventurers in their first serious attempt to do so.

Oliver Cromwell realised the advantages of a dry fenland, but he was against the land grab being made by those financing the draining. After the Civil War, he would be a chief advocate for the completion of the work of the Earl of Bedford, but he was a champion for the rights of the fenmen until he lost his head. One of the drainers sized him up exactly in 1653 with, I am tould that my Lord Generall Cromwell should saye the drayninge of the fens was a good work, but that the drayners had too great a proportion of the land... and that the poore were not enough provided for.

The poore thought so too. The fen people were an independent race of stilt walkers, punters and skaters, living by fishing, wildfowling and farming their summer-dry land, and they were content doing so. Previous attempts at draining had never amounted to much, but now they faced the possibility of losing their land and their livelihood. So, though fated to lose, they fought it. Their fighting against the unwanted incomers of the seventeenth century, the first successful drainers under the Dutchman Cornelius Vermuyden, earned them the name that was to last to the present day fen tigers.

Emerging from the wetness harnessed by Vermuyden was what was to become the richest farmland in Britain. Eventually, there would be 700,000 acres of it, from the silt fens of Lincolnshire to the black peat fens of Cambridgeshire and on into Norfolk, a flat vastness of land beneath an enormity of sky.

How small was man as he went about the business of living, and of dying, there. The Fens have always been a different place. After the draining it became a changed world, the land shrinking in level as the peat dried, but still like nowhere else in Britain. Its people, the fen tigers, the yellowbellies, the fen slodgers, remained the same at heart. Their way of life may have changed, the land dominating their existence as before the water had, but they were the same hardy, stubborn, insular breed that Cromwell had backed.

The crimes taking place in and around the Fens seem strangely fitted to the world in which they were committed. Most have a frisson of singularity that seems to set them in and around the fenlands of East Anglia.

This retelling of some of the crimes which have taken place there through more than two hundred years begins with murder in Whittlesey. Two of the small market towns inhabitants were sentenced to death in 1749, a wife who had poisoned her husband with arsenic and a husband who had cut his wifes throat with a razor. He asked that he might see her burned at the stake in Ely before he kept his own appointment with the hangman.

his work was made possible by the excellent research facilities available at local studies archives, libraries and museums in and around the Fens and the informed interest of their staff, most notably at Downham Market, Ely, Kings Lynn, Lincoln, Littleport, March, Northampton, Peterborough, Whittlesey and Wisbech, and at the University Library and Squire Law Library, Cambridge. Especial appreciation goes to Chris Jakes and Sue Slack of the Cambridgeshire Collection, Cambridge Central Library.

his work was made possible by the excellent research facilities available at local studies archives, libraries and museums in and around the Fens and the informed interest of their staff, most notably at Downham Market, Ely, Kings Lynn, Lincoln, Littleport, March, Northampton, Peterborough, Whittlesey and Wisbech, and at the University Library and Squire Law Library, Cambridge. Especial appreciation goes to Chris Jakes and Sue Slack of the Cambridgeshire Collection, Cambridge Central Library. iarist Samuel Pepys, forced into the Fens in pursuit of an inheritance in the autumn of 1663, thought the area around Wisbech a heathen place where he was bit cruelly by the gnatts. Celia Fiennes, an early travel writer riding around Britain in 1698, had even worse luck in Ely. She found it ye dirtiest place I ever saw and tho my chamber was near twenty stepps up I had froggs and slow-worms and snailes in my roome.

iarist Samuel Pepys, forced into the Fens in pursuit of an inheritance in the autumn of 1663, thought the area around Wisbech a heathen place where he was bit cruelly by the gnatts. Celia Fiennes, an early travel writer riding around Britain in 1698, had even worse luck in Ely. She found it ye dirtiest place I ever saw and tho my chamber was near twenty stepps up I had froggs and slow-worms and snailes in my roome.