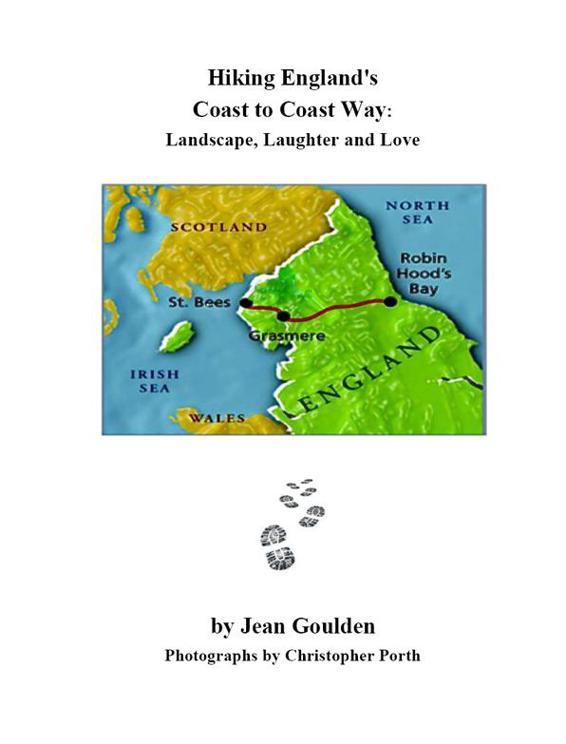

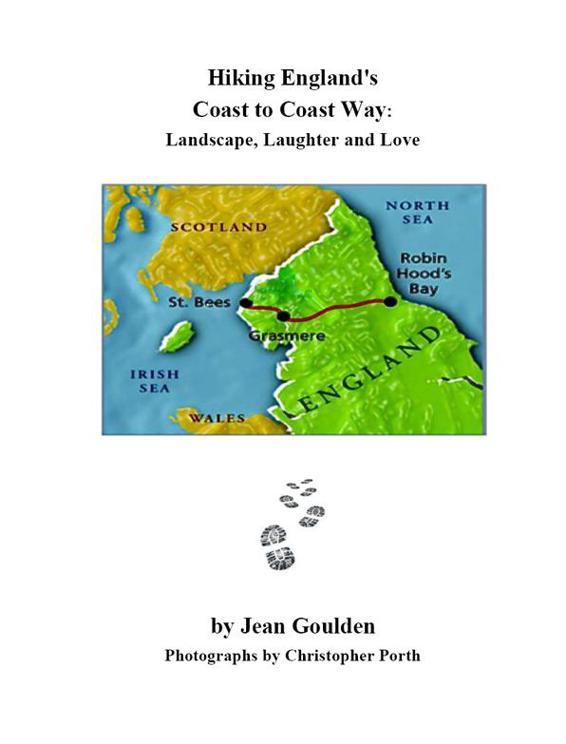

Hiking England's Coast to Coast Way:

Landscape, Laughter and Love

by Jean Goulden

Photographs by Christopher Porth

Published by Jean Goulden at BookBaby

Copyright Jean Goulden, Concord, MA, September 2013

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment and may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

ISBN: 9781483508580

Dedicated to

K, A, and C

Table of Contents

To pickpocket Dickens, it was a beginning; it was an ending. One August, Chris and I joined ten other mis-assorted people and a guide, to walk the Coast to Coast Way. This is a walk devised by British hiking legend, Alfred Wainwright, across the north of England from St. Bees on the west coast to Robin Hoods Bay on the east. By walk, there is a little element of British understatement here: this is no meander along reticent hedgerows or a bucolic ramble across fields of wildflowers; its hard walking, often over very challenging terrain.

By some celestial coincidence, the stars for a dozen people had aligned; our lives would focus on this endeavor for a brief spell, before scattering across the globe.

It was the end of a lifetime of unplanned preparation. It was the beginning of a one hundred and ninety-two mile journey that ended in the North Sea, and also led us all to who knows where. Some fates or forces had molded us into the kind of people who would attempt the Coast to Coast. Some planetary congruence, some elemental finger had prodded, beckoned, tugged us toward this journey, simple and yet profound. Or perhaps, I romanticize, we met, when otherwise we would not have done, we walked, and then we parted.

We greeted our fellow travelers one evening at a Bed and Breakfast in St. Bees. We sized each other upan odd lot, unremarkable in many ways. No Olympians or superheroes, just a bunch of tough folk, mostly peering at the wrong side of middle in middle age. No one said a great deal during that first anticipatory meal. We digested each other as we digested the Cumberland sausage. Like it, we were plain, yet spiced. Spiced with determination, apprehension, courage, awe, and fear. We were three men and nine women, (plus Pete, our guide), and we hailed from Britain, Ireland, Switzerland, Australia and the United States. Walking the Coast to Coast is not like scaling the Himalayas, but for most ordinary people nor is it something you do on a wing and a prayer; it is a response, a debt of gratitude that you choose to pay for getting up in the morning and putting one foot in front of the other. Most of us, perhaps all, had already come a long way.

For me, as I suspect for many, it had all started years ago. Almost imperceptibly the hiking seed had been planted that one day would twine into the vine of this new adventure. Perhaps it was the day my dad had taken us for a little walk. We were on a caravan holiday in the Lake District. I was perhaps ten years old. The day dawned like a picture postcard, a blue sky decorated with Constable clouds (as so often painted by the late 18 th century British landscape artist) and strung with birdsong. My dad led us on a path that wound slowly up a hillside. At first, the unaccustomed effort of it winded me, but after a while, the challenge of it excited me. I could go higher and higher. We walked for a long time on what seemed like a carnival day. Troupes of other walkers shared the paths with us, cheerily greeting one another in the uninhibited way of outdoors folk. The air vibrated as birds chirped, insects hummed, and languid sheep called each other without alarm. The grass was vivid green, the flowers streaks of sunlit yellow and laundry bright. All was very well with the world. Occasionally, we paused and debated whether to press on or turn back. I urged us higher, higher, yet higher until, at long last, to my mothers shocked surprise, we came to Striding Edge, the knife-edge path that leads to Helvellyn, the Lake Districts highest peak. My dad delighted in regaling us with stories of hikers who had mis-stepped here and slithered to an untimely end. My mother quailed, but before very long we had somehow reached the summit and felt like conquerors of all we could see. It was my first taste of the thrill of hiking achievement: the endorphin rush, the wind in my hair, the glow of health, the endless possibilities. It was wonderfully heady stuff. It felt like clear, dewdrop joy.

We were utterly unprepared to climb Helvellyn, carrying, as I recall, neither food, nor water, map, nor compass. By all the lore and legend of hiking, we should have been in peril, but our luck held. The weather remained perfect; we were safe, our limbs ached but did not twist, sprain or break, and we even found a happy caf in the late afternoon after our descent, that served us tea and bacon sandwiches. Ambrosia of the gods!

And so, in quite the wrong way, my love of hiking was spawned. Maybe it was inevitable. Fated. Programmed in the genes. Who knows what is predestined or the outcome of a string of inconsequential choices? I was raised in the curdling milk and gritty honey of industrial Yorkshire, but as I learned later, my predecessors had escaped the mills and the mines whenever they could to walk the fells and dales. They had courted with the open spaces, the whipping winds, the soft breezesas they courted one another. Men who had returned from the insanity and gash of war were gentled and steadied by the rhythm of striding up to high places. Broken spirits and broken bodies received some balm. Unlike the farmers and millworkers before me, I was privileged with a formal education, financial and physical security, no alarms of action on a foreign field; but as I discovered hiking, I began to realize that we shared a visceral joy, a joy to which poets and mystics aspire.

As the train neared St. Bees, the scenery rushed backwards past me in a blur. I felt dislocated. My mind too was a blur, as if someone were vigorously unspooling my life. So much had led to this. Not just the teenage, youth hostelling jaunts, the weekend hikes of my early married life, the long trip of two decades ago, but much, most, perhaps all that had happened since, not to mention a freckling of the lives of those who had gone before.

Over twenty years ago, our neighbors, cheerful, cash-strapped teachers, had spent their summer walking The Pennine Way. This is an even longer walk than the Coast to Coast, sinuating up the spine of Britain, then stretching on across the Cheviot Hills and into Scotland. There is little romance about The Pennine Way; it is not satisfactorily cradled by the sea, nor does it confront many mountains, or long stretches of spectacular scenery, but to the persistent walker it has its appeal. Its draw has much to do with the timeless invitation to become engaged, to be involved with the minutiae of life in industrial hamlet, slanting heath, alien listening station, and with the welcoming old woman who served tea and scones in her Garrigill front room.

I remember there was something magnetic about Jan and Gordons stories of the long trudge through bogs and across wind-lashed moorssomething that claimed us, something elemental, possibly perverse. For a while we were seduced into stripping our lives to what could be carried in a backpack and propelled by our own strength and will. Inevitably one July, after three weeks of rugged rain, we set out on The Pennine Way. It was indeed a long slog through bilious bogs and across wind-groined moors. And yet, I began again to grasp the lure of long-distance walking. It is about getting there, but it is not only about getting there; we rediscovered the truism that the journey is as important as the destination. Long distance walking is a lot like chasing butterflies, shedding the chrysalis of humdrum cares, taking flight, crash landing and mending broken wings. Its odd now to picture us as skipping around with insect nets and etymological reference books, when in reality we plodded in hiking boots and raingear through the mists and gloom, but we were making new discoveries, some of them about how the physical, the emotional and the spiritual aspects of our lives are intertwined. There are new rhythms to the hiking life, one foot in front of another, one foot in front of another, left, then right, left then right, and the larger rhythm of eat, sleep, walk, eat, sleep, walk. Paring of life peels to its core, we walked in step with the worlds heartbeat, the rise and roll of the tide, the crescent and crest of the moon, the spurt and sigh of creation. In the midst of these eternal, mesmeric rhythms, my mountaintop experience broke through.

Next page