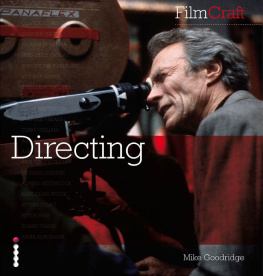

Film Craft

Directing

Mike Goodridge

ILEX

First published in the UK in 2012 by

ILEX

210 High Street

Lewes

East Sussex BN7 2NS

www.ilex-press.com

Copyright 2012 The Ilex Press Limited

Publisher: Alastair Campbell

Associate Publisher: Adam Juniper

Managing Editors: Natalia Price-Cabrera and Zara Larcombe

Editor: Tara Gallagher

Specialist Editor: Frank Gallaugher

Creative Director: James Hollywell

Senior Designer: Kate Haynes

Designer: Grade Design

Digital Assistant: Emily Owen

Picture Manager: Katie Greenwood

Colour Origination: Ivy Press Reprographics

Any copy of this book issued by the publisher is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including these words being imposed on a subsequent purchaser.

Digital ISBN: 978-1-907579-54-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form, or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or information storage-and-retrieval systems without the prior permission of the publisher.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The FilmCraft series is designed to explore each of the film crafts through interviews with some of their greatest practitioners, and the first books in the collection, Cinematography, Editing, and Costume Design, have done just that. The directing book, however, presented a variety of additional challenges because directing, perhaps the greatest of the crafts in this collaborative art form, encompasses direction of all the crafts as they relate to the thematic and stylistic essence of the entire enterprise. To encapsulate the craft of sixteen directors in this book is to illustrate the complete process of filmmaking.

The buck stops with the director, of course. If the film works, he or she will be the first to receive acclaim; if it fails, he or she will be blamed for that failure. The pressure on a director throughout the process is enormous. On set the director has not only to realize his or her vision as it was conceived, but to answer every question, put out every fire, respond to the performance as it happens, ensure that the dialogue rings true, and guarantee that there is enough coverage for the edit. In post-production, the director works with the editor to put it all together with the myriad possibilities the digital editing process allows, overseeing sound, music and dubbing, and appeasing financiers anxious that the finished product will please audiences. Filmmaking is as grueling and intensive as it is exhilarating. While actors and crew move on to their next projects, sometimes making two or three films a year, most directors take two years or more to finish one film, unless you are Woody Allen or Michael Winterbottom, whose prodigious outputs are anomalous.

Is it any wonder that the director has to have an ego? For at least a year or two, and sometimes a lot longer, a director has to believe his or her vision in a project and keep it alive and intact while the process itself and the hundreds of people involved often attempt to chip away at its integrity. Filmmaking therefore requires the stubbornness of a mule, but it also demands that the director listen to those around who can make valuable contributions or positive changes. And during production at least, the filmmaker dictates the mood of the set, has the final word on a multitude of day-to-day decisions, and is required to manage a company of people usually larger than most businesses.

Choosing sixteen filmmakers for this book was no easy feat. I wanted a range of styles and nationalities; I wanted some writer/directorsor classic auteurs, if you likeand some directors who take on existing screenplays and make the projects their own. I wanted some filmmakers who had been working for many decades and some with just a few outstanding films under their belt. I wanted some who are the darlings of the arthouse circuit and some whose films would happily sit on three screens of a multiplex.

The pleasure in the experience of talking with such a variety of filmmakers is that they are all vastly different personalities with different ways of making movies, while their goals remain pretty much the same. Authenticity, whether contextual or emotional, is clearly the idealand that is all within the construct of each film, so Guillermo del Toro is as determined that his monsters appear authentic in the troll market in Hellboy II: The Golden Army as much as Paul Greengrass wants to recreate the hijacking of Flight United 93 with as much literal detail as he can muster. Susanne Bier talks of her bullshit detector, which ensures that every nuance of the performance and dialogue in her intense dramas ring true, and Peter Weir describes the reduction of the crucial farewell scene in Witness from over-written Hollywood gushing to a simple, unspoken goodbye. Of course, a kind of authenticity is just one element in the patchwork of intent.

Every director has his or her own distinct approach. When youre watching a clip from a Pedro Almodvar film, you know within seconds that you are watching his work because of the characteristic mise-en-scne, design and colors, the familiar actors, delicious dialogue and score. On the other hand, Frances Olivier Assayas is no less an auteur than Almodvar, but it is not easy to call an Assayas film: this, after all, is the man who made the visceral action epic Carlos, the meticulous costume drama Les destines sentimentales, the cyber-sex thriller Demonlover, and the languorous French chamber piece Summer Hours. His personality is less an obvious factor in his work.

Some of the filmmakers like Peter Weir, Guillermo del Toro, Terry Gilliam and Paul Greengrass have flipped in and out of the Hollywood studio system, making films as broad as Dead Poets Society or the Bourne and Hellboy films. But they are all practiced at maintaining their visions while working within the mainstream studio system. Others in the book probably couldnt survive within those parameters. When I spoke to him, Del Toro was in Canada in pre-production on his latest megapicture, an aliens-versus-robots movie called Pacific Rim, which has already been set for release as a tent-pole picture in summer 2013. You can hardly imagine the Dardennes or Nuri Bilge Ceylan even knowing what to do on a film of that type or scale. Does that make Del Toro less of an auteur? On the contrary. He is a different breed of director, who can move between smaller, more intimate films like The Devils Backbone and Pans Labyrinth, and large-scale epics for which he has the ambition and aptitude. Zhang Yimou is similar: the same voice behind the glorious simplicity of The Story Of Qiu Ju or Not One Less can also command a cast of thousands for Chinese blockbusters like

Next page