Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Dedicated to my teachers, and in memory of the first and best of them, my father, Theodore Blunk

We are not human beings having a spiritual journey. We are spiritual beings having a human journey.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (18811955)

James Wrights life was shaped by a rare depth of compassion, a moral shrewdness as keen as George Orwells, and an almost helpless devotion to poetry. Nearly four decades have passed since the poets death in 1980, yet new readers are continually drawn to the excellence of Wrights work. The speaker welcomes us into these poems, and readers feel acknowledged and respected. Sharp details from Wrights life are found throughout his work, moments of feeling that are captured with richness and clarity. He wants to tell the human, often painful, truth. Ranging from delicate lyrics to desperate curses, the voice in his poems claims great authority.

From the age of ten, Wright worked hard at his poetry, with the same care and determination he saw in his father, a factory worker. Wright used poetry as a way to survive and finally to escape from the dead-end life that threatened to trap him in the Ohio River Valley. He rarely went back after joining the army at the age of eighteen, but in a way, all of Wrights poems are addressed to the Ohio River and to the people who lived and worked along its banksthe townspeople in Martins Ferry, Ohio. Wright includes them in the audience he creates for his poetry, the hard-pressed, resilient southern Ohioans he knew growing up in a steel town during the Depression. Many of his poems confer dignity on their inner lives.

Wright had an associative, musical intellect, aided by a startling phonographic memory that gave him the ability to recite poems and prose for hours on end. After saying poems in Latin, German, Spanish, or French, he would improvise his own translations. His poems first won acclaim for their skillful use of metrical forms and patterns of rhymean academic verse that valued convention. This classical streak in Wrights character proved an asset in his career as a professor of English literature. But in his poetry Wright was fearless, absorbing the free-verse and image-based strategies he found in Whitman and in the wealth of new translations of world poetry in the 1960s. The German and Spanish writers he translated influenced Wright more than the poems of his American contemporaries.

The success of his 1963 volume, The Branch Will Not Break composed almost entirely of free-verse poemsencouraged the idea that Wright had dramatically turned his back on metrical poetry. But like many other stories that have gathered around Wrights name, this is false. He never stopped writing poems in rhyme and meter. Wright wanted only to expand the range of possibilities available to him. In his last decade, he returned to the spoken rhythms and idioms of his native Ohio. His lyrical prose pieceslike his journals and lettersshow astonishing fluency of language, thought, and feeling. Over multiple drafts, Wright alternated between prose and line-break versions of his late poems, listening for their proper form. Having achieved a thorough mastery of his craft, Wright found the patience and focus to let the poem at hand emerge in its own good time.

* * *

As I describe in the acknowledgments, this biography has had a long period of gestation, and it benefits from many years of research. I worked closely with Wrights translations and have also made a study of his personal library, where the margins of his books still shout his praise and invectives. I recorded hundreds of hours of interviews and public tributes to the poet, and found that everyone who ever met Wright could recall him vividly. That strong sense of Wrights physical presence can still be felt in recordings of his readings. I have transcribed more than four dozen of Wrights public talks, readings, and interviews, wanting to keep his voice at the center of this book.

I also quote extensively from unpublished journals, letters, and poems, thanks to the unrestricted access I have been given to Wrights papers. One extraordinary collection of letters, written between 1957 and 1959, chronicles Wrights deliberate creation of a Muse that could sustain his poetry. He sometimes referred to these unpublished letters as a separate journal, and they possess a profound intimacy. Two decades later, in the months of Wrights final trip to Europe in 1979, his journals contain some of his best writing, nearly all of it as yet unpublished. As a result of my focus on this unknown work, Wrights published poems appear here less often. They can be found in his Complete Poems, Above the River , or the fine Selected Poems edited by Robert Bly and Anne Wright.

My hope has always been to turn attention back to the poems, which include some of the most influential and enduring lyrics of the past century. Wrights life, by turns despairing and inspiring, is always fascinating. But as he would remind us, it is finally the work that matters. I feel grateful to have spent so much time in Wrights company.

JulyAugust 1958

He knew he had to write one last poem before he could quit. Thirty years old, he had tried many times to give it up, but now he swore to the Muse that he was through. On the morning of July 22, 1958, James Wright began His Farewell to Poetry.

All that summer, Wright woke before dawn, impatient to get to work. The light grew slowly in his basement study. Two huge molten glooms of oak trees shaded the house, and rusted awnings at ground level hooded the small windows near the ceiling. For a desk, Wright had placed a wooden board on sawhorses, with a gooseneck lamp and a typewriter on top. Plank bookshelves stacked on cinder blocks stood against the walls; floor beams and heating ducts were crowded above his head. In the dawn quiet, he heard songbirds and the rough shuttle of freight trains crossing above Como Avenue, where rows of small houses stood on narrow plots a mile from the University of Minnesota campus in Minneapolis.

Wright always felt that daybreak was the best time for writing. There is something uncluttered and clear and living about the air at that time of day. The basement stayed cool despite the summers brutal heat, and these early hours were quiet while his five-year-old son, Franz, and his wife, Liberty, slept. As July drew to a close, the Wrights second child was due any day.

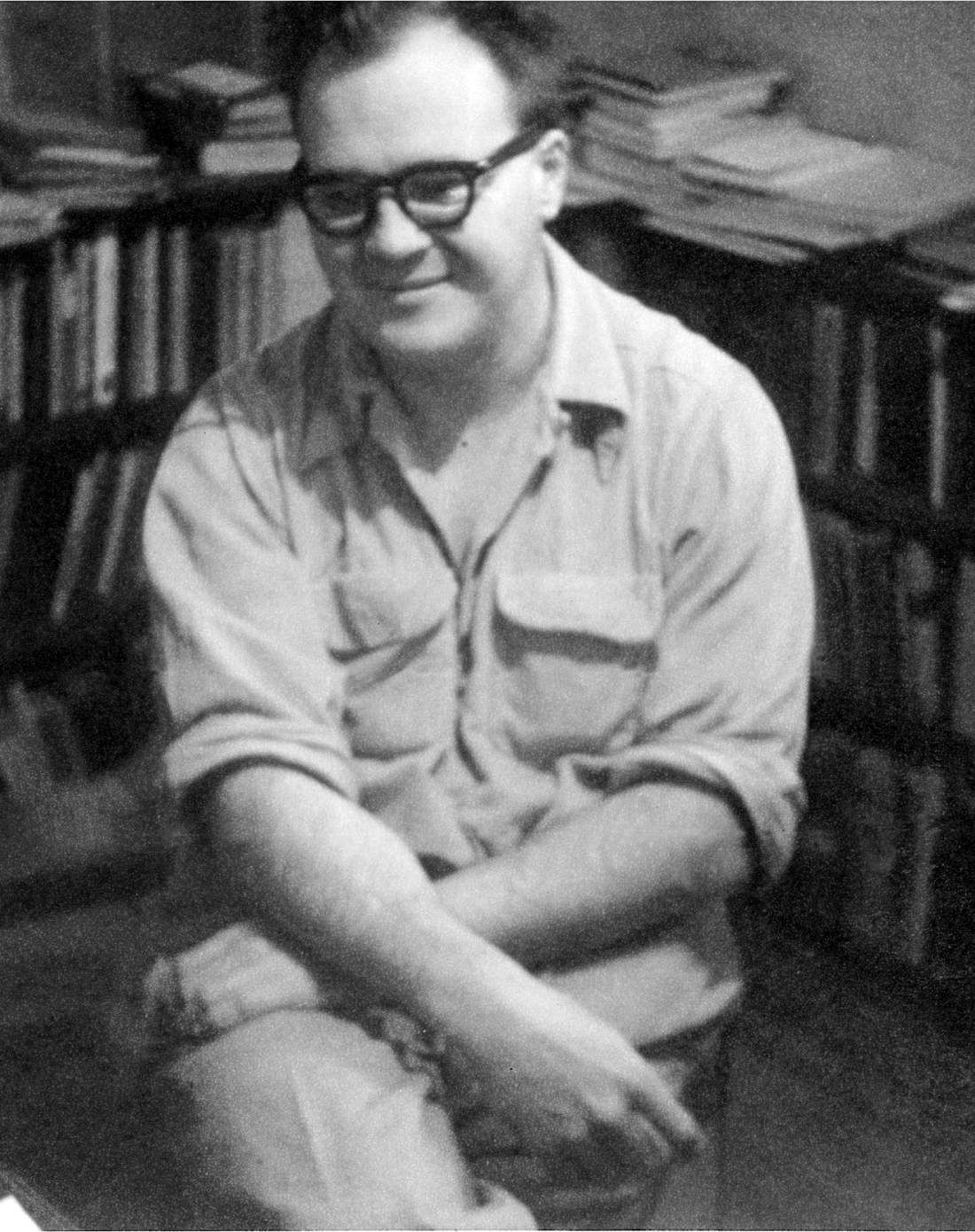

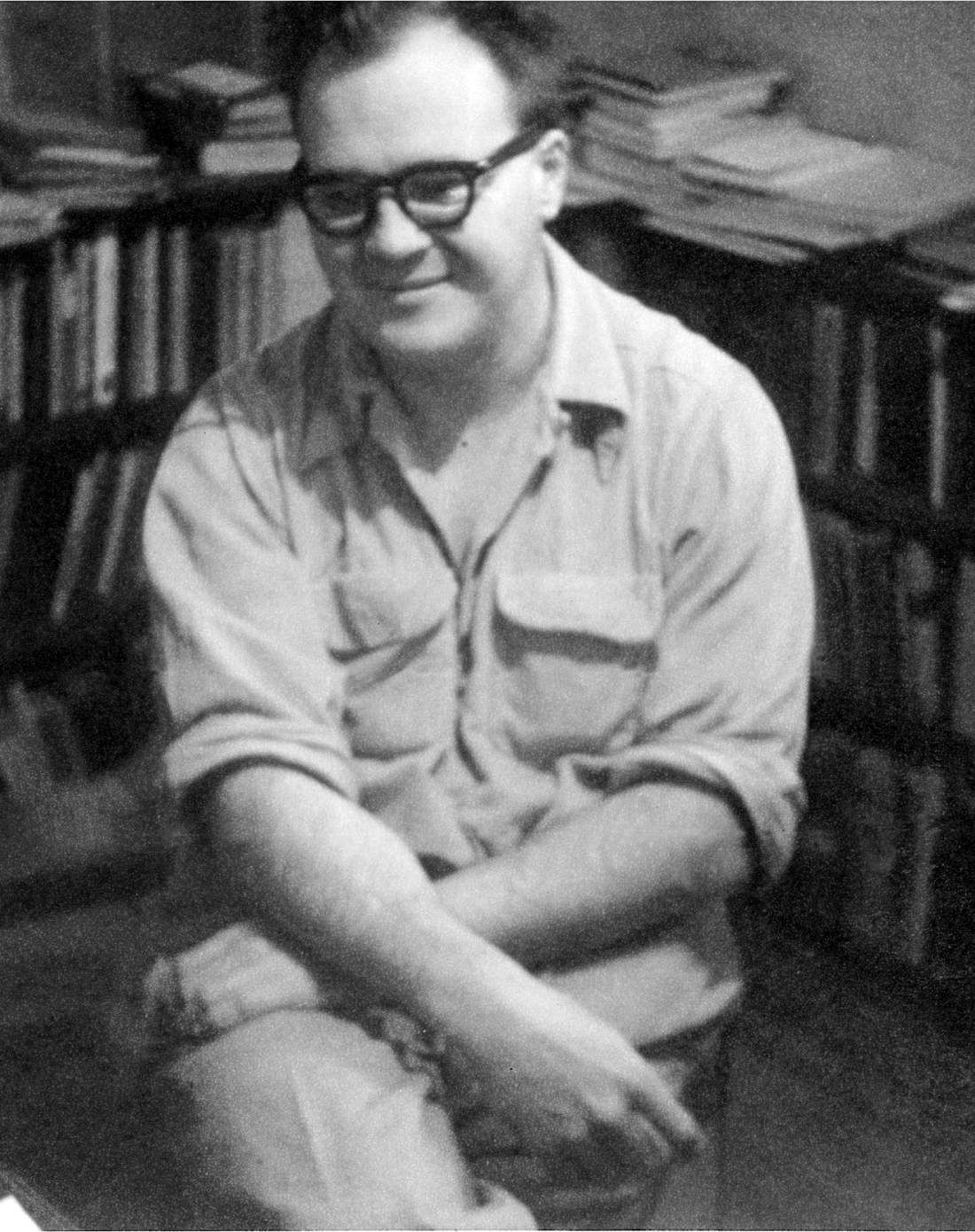

Standing five foot ten, Wright was not tall, but he was solidly builtlike a football player, many said. His light brown hair was growing thin; his wide-set brown eyes bore a sharp intensity until laughter gave him a mischievous squint. On his round face he wore horn-rimmed glasses that slipped from the too-small bridge of his nose. Reflexively, he pushed them snug with a finger stained by nicotine. At his desk, he alternately typed or wrote in a cramped, rounded script. Even with the windows propped open, cigarette smoke hung near the ceiling as Wright worked for hours in what he described as this crazily organized study of mine (utterly alone in a corner of the basement, partitioned off by stained hardwood walls).