Copyright by Jonathan W. White

Cover and internal design 2015 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Lynn Harker/Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover images/illustrations SuperStock

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

Published by Cumberland House, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

For my prelaw students at Christopher Newport University

When Abraham Lincoln left Springfield, Illinois, for the White House in February 1861, he turned to his law partner, William H. Herndon, and said, Billy, over sixteen years together, and we have not had a cross word during all that time, have we?

Not one, replied Herndon.

Dont take the sign down, Billy; let it swing, that our clients may understand that the election of a President makes no change in the firm of Lincoln and Herndon. If I live, Im coming back, and we will go right on practicing law as if nothing had ever happened.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Lincolns Advice to Aspiring Lawyers

Lincolns Character as a Lawyer

Lincolns Advice to His Clients

Lincolns Preparation for Trial

Lincoln in the Courtroom

A Lawyer in the White House

INTRODUCTION

In October 1857, Abraham Lincoln defended a seventy-year-old woman named Melissa Goings, who was on trial for the murder of her husband. Melissa and her seventy-seven-year-old husband, Roswell, had apparently been living rather disagreeably for some time. On April 14, 1857, the two got into a fight over whether or not to open a window. Roswell allegedly tried to choke Melissa; she therefore claimed to be acting in self-defense when she whacked him over the head with a stick of firewood. I expect she has killed me, Roswell told a neighbor after the scuffle, adding, If I get over it I will have revenge. He died four days later.

As the trial got under way on October 10 at a small county courthouse near Peoria, Illinois, Mrs. Goings was nowhere to be found. A court officer accused Lincoln of encouraging his client to escape, but Lincoln denied the charge. I didnt run her off, he told the court. She wanted to know where she could get a drink of water, and I told her there was mighty good water in Tennessee.

Abraham Lincoln was a talented, practical lawyer. In fact, Lincolns success as a politician and statesman was rooted in his experience as an attorney. His presidency was plagued by constitutional problems and legal crises. Yet he deftly led the nation through a great civil warour nations most divisive constitutional conflictin large measure as a sensible prairie lawyer in the White House.

As a young man, Lincoln taught himself the law. He quickly became one of the most prominent attorneys in Illinois, handling every type of case imaginablemurder trials and other criminal proceedings, bankruptcy filings, divorces, larceny, trespasses, ejectments, railroads and big business, libel and slander, civil disputes, and debt collection. Lots of debt collection. But Lincoln did not deal only with trials in the lower courts. He also argued nearly 350 cases before the Illinois Supreme Court and one case before the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, DC.

Young men in Illinois often looked to Lincoln for insight into how to become an attorney (only men could practice law in those days). Through letters, speeches, and informal conversations, Lincoln gave them advice based on his experiences. Lincolns wit and wisdom are still relevant today for both aspiring lawyers and practicing attorneys. Indeed, while the legal profession in the United States has changed in many ways over the past century and a half, many of Lincolns principles are timeless.

In a larger sense, Lincolns advice for lawyers is also relevant for people who work outside the legal profession. As we will see, Lincoln believed the highest duty of a lawyer was to be a peacemaker in his community. Therefore, any reader who deals with interpersonal conflict can learn from Lincolns insights. Indeed, Lincolns lessons for attorneys can apply to almost any walk of life.

The words in the chapters that follow come directly from Lincoln and his friends. Many come from Lincolns own correspondence. Others are recollections of those who knew him. Some of his friends stories may be exaggerated or embellishedsome may even have been fabricated or misremembered when they were recalled so many years after Lincolns death. But perhaps we can learn as much about what it means to be a good lawyer from the myths and legends about Lincoln as we can from the reality.

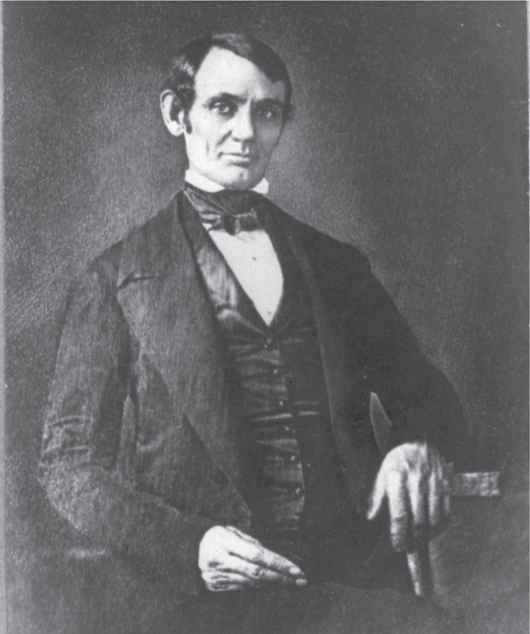

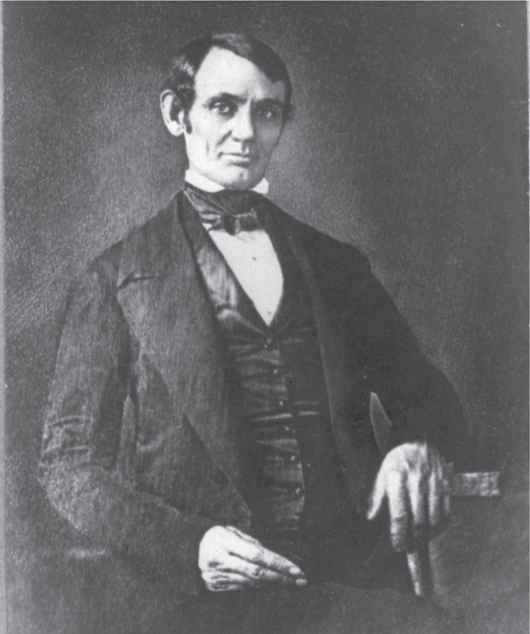

This daguerreotype, taken in about 1846 when Lincoln was elected to Congress, depicts the young lawyer in Springfield, Illinois. It is the earliest known photograph of the future president. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

CHAPTER 1

IF YOU WISH TO BE A LAWYER

Lincolns Advice to Aspiring Lawyers

In the nineteenth century, it was much more common for an aspiring lawyer to read law in the office of a practicing attorney than to attend law school. Law schools were few and far between, especially on the frontier. In Chicago, for example, only five of the forty-four attorneys who practiced between 1830 and 1850 had attended law school.

In the mid-1830s, Whig attorney and state legislator John Todd Stuart encouraged young Abraham Lincoln to become a lawyer. Lincoln started his study of the law in New Salem, Illinois, by borrowing law books and reading them. He borrowed books of Stuart, took them home with him, and went at it in good earnest, stated an 1860 campaign biography. Another campaign document described Lincolns intense study of the great eighteenth-century English jurist William Blackstone:

He bought an old copy of Blackstone, one day, at auction, in Springfield, and on his return to New Salem, attacked the work with characteristic energy. His favorite place of study was a wooded knoll near New Salem, where he threw himself under a wide-spreading oak, and expansively made a reading desk of the hillside. Here he would pore over Blackstone day after day, shifting his position as the sun rose and sank, so as to keep in the shade, and utterly unconscious of everything but the principles of common law. People went by, and he took no account of them; the salutations of acquaintances were returned with silence, or a vacant stare; and altogether the manner of the absorbed student was not unlike that of one distraught.