ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During the 20082009 academic year, the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at the University of Richmond was fortunate to sponsor an exceptional set of papers and lectures on Abraham Lincoln. Honoring the 200th anniversary of Lincolns birth on February 12, 1809, the Jepson School focused its yearlong Jepson Leadership Forum on Lincolns Legacy of Leadership. The chapters in this, the fourth volume in the Jepson Studies in Leadership series, present ten exceptionally insightful perspectives on Lincolns leadership. First and foremost, we are grateful to the talented group of scholars who contributed to our efforts to better understand Lincoln. Working with them has been a great pleasure, and it has deepened our understanding of Lincoln and his time.

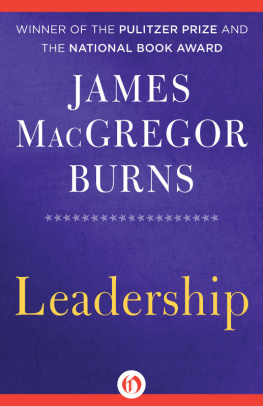

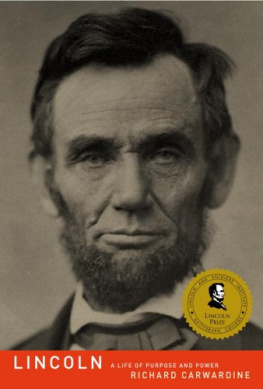

The chapters by Herman Belz, Jeffrey Sedgwick, Daniel Walker Howe, Jennifer Weber, Joseph Glatthaar, and Brian Holden Reid were presented at a colloquium on Lincoln held at the University of Richmonds Jepson School on September 1213, 2008. We are grateful to each of them for preparing excellent essays, and for contributing to the many lively discussions we had during our time together. Richard Carwardine presented the James MacGregor Burns Lecture on Leadership Studies and Biography as an additional part of the September colloquium. We are grateful to him as well for a magnificent essay on Lincolns wonderful self-reliance. Of course, neither the colloquium nor the Burns Lecture would have been possible without the assistance of Nancy Nock and Sue Robinson Sain. Nancy made all the travel, dining, and lodging arrangements for both our visitors and local participants in the colloquium. These events would not have happened without her. Sue deftly handled the arrangements for Professor Carwardines lecture.

Later in the year, University of Richmond president Edward L. Ayers, Professor Douglas L. Wilson of the Lincoln Studies Center in Galesburg, Illinois, and University of Virginia professor William Lee Miller presented wonderfully rich lectures on aspects of Lincolns character and leadership. Their presentations usefully complemented the papers given in September. Shannon Short Best was exceptionally helpful in assisting Sue Robinson Sain in arranging those three lectures.

Tammy Tripp has done a wonderful job in keeping the editors more or less on schedule and on-task. We are grateful for her well-calibrated nudging, and her wise suggestions. And we have benefited greatly from her skillful editing of the entire manuscript.

In addition to the Jepson School staff members, we are pleased to thank Dean Sandra Peart for her encouragement and strong support. We are lucky to be on the Jepson faculty, and Sandras leadership has contributed greatly to our good fortune. We also thank the Jepson Studies in Leadership series editors Terry L. Price and J. Thomas Wren for helping us plan the fall colloquium and for their wise counsel in coordinating this set of essays with the earlier series volumes.

Our editor at Palgrave Macmillan, Laurie Harting, has been unusually wise and patient in helping us sort out various contractual questions and in guiding the project to completion. We are also grateful to Laura Lancaster at Palgrave for her assistance in cheerfully working with us through the books final publication.

Finally, we want to thank our wives, Marion and Brenda, for their understanding, patience, and support. They make it all possible.

CHAPTER ONE

What Lincoln Was Up Against:

The Context of Leadership

E DWARD L. A YERS

In the bicentennial of Abraham Lincolns birth, we justly celebrate his character, ideals, and strategies, finding new depths in his virtues. It is tempting to imagine that the halting and hard-won evolution of Lincolns ideas and strategies on emancipation marked the moral growth of white America during the Civil War. But that story, implicit and explicit in many portrayals of Lincoln, embodied in our monuments to him and inscribed in our favorite quotations, underestimates Lincolns greatest accomplishment.

Abraham Lincoln faced desperate challenges from the moment he took office until the day he was killed. While Union armies in the field struggled for four years against dismayingly effective Confederate forces, Lincoln fought to keep the North from breaking apart. The task proved unrelenting. Abolitionists and Radical Republicans pressed Lincoln to act more boldly against slavery while many Democrats swore, start to finish, that they would not fight a war on behalf of black Americans.

Lincoln could never be confident that the gains he won would long endureor would even endure through the next election. Despite his eloquence and skill, and despite the Unions growing success on the battlefield, white public opinion in the North refused to consolidate behind Lincolns leadership on the key issue of black Americans and their future. A wary egalitarianism among some Republicans early in the war grew into genuine respect for black Americans, especially black soldiers, but in turn Democrats developed ever more contemptuous and systematic arguments and rhetoric against black people. The Republicans, as a matter of political calculation if nothing else, talked of black Americans cautiously and intermittently. The Democrats, by contrast, sneered and raged about negroes at every opportunity and found receptive audiences across the North whether events on the battlefield went well or not. The war divided the white North ever deeper even as black freedom grew closer, compromising reconstruction before it ever began.

As much as we would like to imagine that the eloquent words from the Gettysburg Address and the second inaugural spoke for a white North made greater and more self-aware through the sacrifices of the Civil War, those words do not seem to have penetrated very deeply into the consciousness of those not already inclined to agree with them. Lincolns great speeches, when not ignored, were ridiculed and dismissed by his many enemies. His words gained their resonance in decades and generations that followed, when the nation told the story of the Civil War back to itself, trying to make the shattering experience coherent and whole.

None of this diminishes Abraham Lincoln. His actions against slavery, driven by military necessity, outran his commitment to black Americans early on, but his faith and understanding grew as he witnessed the bravery of African American soldiers and as enslaved people made clear their determination to be free, regardless of the cost. Lincoln grew morally over the course of the war and he shared that growing understanding in ever more eloquent words. Lincolns most important triumph lay, however, in leading the nation to a place many did not choose to go, in navigating through the political, ideological, and emotional minefield that was wartime America. Though Democrats and other opponents fought against white Southerners on the battlefield and believed in the Union, they shared white Southerners views of black Americans. They did not undergo a conversion experience in the Civil War, despite the often lonely and brave eloquence of Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln realized better than anyone how much public opinion mattered. In this age, and this country, public sentiment is every thing, he said. With it, nothing can fail; against it, nothing can succeed. Whoever moulds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes, or pronounces judicial decisions. If we want a clear sense of Lincolns actual accomplishments, then, we must deal with public opinion more systematically than we have. There were no opinion

Americanseven generals and presidentsunderstood the larger shape and meaning of the Civil War through printed words. Only a tiny fraction would have seen or heard Abraham Lincoln and most white Northerners would never have seen an enslaved person or a battlefield. The war came in long gray columns of text, chosen and framed by local editors. A new system of telegraph stations, railroads, and press organizations spread words with unprecedented speed and in enormous quantity. Reports from the battlefield poured out in brief messages and long torrents, editorials commenting on every event and utterance. As desperate as the war was, and as bitterly as people disagreed, the Lincoln administration largely allowed the opposition press to say what it wished.