Foreword

When Kathryn Johnson walked into The Associated Press Atlanta bureau in 1947 looking for a reporting job, there were no women and they werent welcome, she recalled. She took a job as a secretary in the bureau with a possibility of someday becoming a journalist. She waited 12 years.

Johnsons reporting career moved faster. She was assigned to the burgeoning civil rights movement because she was young, green and cheap labor, she said, and because the many white men of the times wanted nothing to do with covering sit-ins, marches and tense black-and-white standoffs.

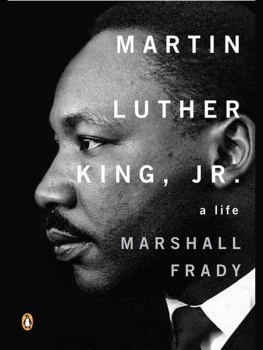

Johnson rose to become one of the news agencys pre-eminent reporters on the American civil rights era. A deep understanding of Southern culture and people helped her grasp and give voice to the historical transformation taking place. A determined and gracious style got her unprecedented access to the major figures of the time, notably the family of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In her nearly 20 years of reporting for AP, she would break some of the most important stories. Beyond civil rights, she covered the My Lai massacre hearings and the court-martial of Lt. William Calley, the travails of the wives of American POWs in Hanoi and their eventual release and readjustment to civilian life.

There was a fearlessness about her when on assignment. She was petite, only 5 feet 3 inches, but never too worried about some of the very dangerous situations that took place. She had an ability to look the part, dressing as a coed to sneak into class alongside Charlayne Hunter when she integrated the University of Georgia in 1961.

Born in 1926 in Columbus, Georgia, to John Lewis and Lula Boondry Johnson, she grew up in a strictly segregated world. Everything was black and white, she said. It never occurred to me that this was wrong, segregation.

She described her childhood as part Huckleberry Finn, trailing an older brother and his friends sometimes into trouble and at other moments into danger. She was rescued from drowning by two elderly African-American fishermen as a small boat she was floating in sank in the Chattahoochee River. Later the boys shot a tin can off her head with a .22-caliber rifle as she replaced the can after each shot. Fortunately, they were excellent shots, she said.

Throughout her career, Kathryn encountered the standard treatment of women of the era and bureau life. One day she would be taking dictation and compiling high school sports scores. On another she would be in the street covering what likely was the top story in the nation.

When she found herself still assigned to dictation and sports scores even after completing a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard, she decided to leave the AP. She worked for U.S. News and World Report in Washington and later for CNN in Atlanta.

But her heart remained with AP and its mission. She fell in love with writing and reporting at a young age. She embraced the front lines of journalism and its eyewitness role to history. Shelike many of the people she coveredtasted discrimination firsthand. Kathryn Johnson never turned bitter. She embodied journalisms highest idealsthat the work we do ultimately makes the world better, fairer and safer. In so doing, she inspired generations of AP colleagues, both male and female.

Tom Curley

Former AP president and CEO

Introduction

For more than 10 years, I had known Kathryn Johnson as she covered the civil rights movement and the historic change that swept the South.

Kathryn always observed scrupulously the highest standards of her profession while reporting on one of the most important continuing struggles in our country with objectivity, thoroughness and fairness. Like many other reporters, she sometimes faced personal danger in order to fulfill those duties.

Whenever anything was happening, Kathryn seemed to be there.

She has written of being trapped in an outside phone booth by several Ku Klux Klansmen when a Freedom Bus was arriving; locked in a deli in downtown Atlanta along with students trying to integrate; and forced to sit in a hot courtroom gallery while covering the trial of two Klansmen for the random killing of a black Army Reserve officer, Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn.

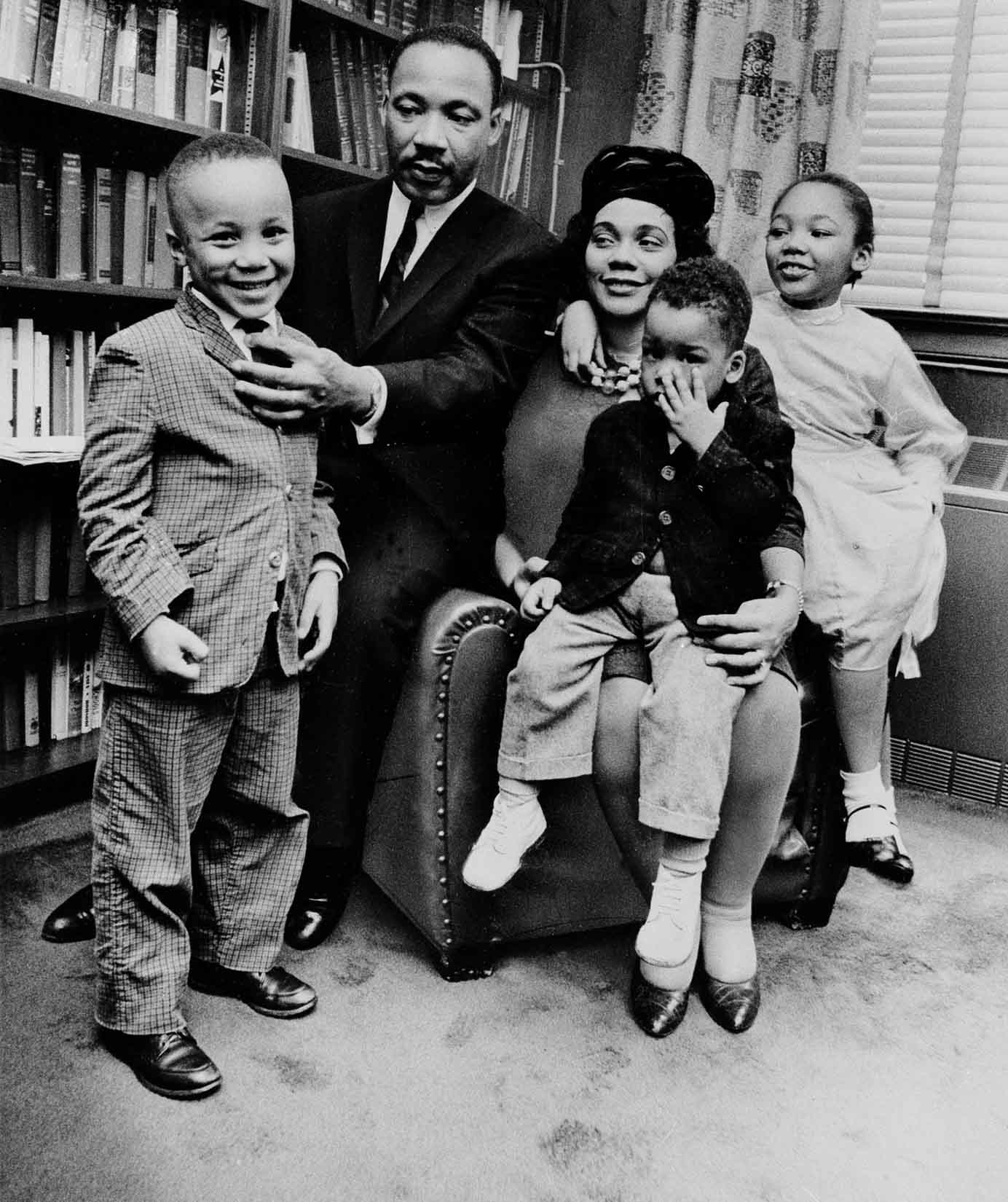

I remember when Coretta Scott King spoke of Kathryns remarkable tenacityin that she alone, of all those involved in the racial conflict, covered the King family for three generations. Starting with Martin Luther King Jr. on his return to Atlanta after heading the fight in Montgomery, Alabama, to integrate city buses, she persistently followed King and the Movement through the whole of his tumultuous career.

And that, along with friendship with Coretta after years of interviewing her, is why Coretta allowed Kathryn, alone of all the journalists covering civil rights, to be present in the King home on the night her husband was assassinated and every subsequent day until his burial.

Of all the significant stories Kathryn reported, those of the civil rights movement mean the most to her. Moreover, her reporting on racial conflicts, murder trials, assassinations and protests managed to secure access for AP photographers, resulting in exclusive, historic photos that may have been impossible to obtain otherwise.

In Kathryn I have observed such qualities as boundless curiosity, impressive character, humility and fidelity to her work. Such thorough, accurate, courageous and firsthand reporting is sometimes slow, and by the standards of todays social media generation, may seem old-fashioned. But of such stuff is a great reporter made.

And that is a precise description of Kathryn Johnson.

Andrew Young

Former mayor of Atlanta and U.N. ambassador

Preface

As a white girl born and reared in the Deep South, I grew up in a rigidly segregated society. I always thought, Thats the way it is. Id barely begun as a full-fledged Associated Press reporter when that thought was quickly transformed by the civil rights struggle that was spreading rapidly across the South in the 1960s.

I first began covering Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1960 at news conferences, sit-ins and demonstrations, when he was a young, fairly unknown Baptist minister. But it wasnt until he ended a strike near downtown Atlanta and I offered him a ride home that I began to really know King and his wife, Coretta, personally.

Id written features for the state wire about Coretta and how she had given up a promising singing career to marry King and about the difficulties of caring for four children while her husband was often out of town. Occasionally, Coretta invited me to have lunch with her and I would often visit for a chat. Ill always remember our time together.

The 60s were powerful days. Blacks were taking to the streets while America was pouring more and more of its blood and money into the Vietnam War. To say I was unprepared for plunging into chaotic events is an understatement. I had not the slightest idea of what Id be facing. Yet, in the first few years, I was trapped and rattled in an outside phone booth by Ku Klux Klansmen; held at gunpoint by an Alabama state trooper and a taxi driver; hit by rocks and tear gas in race riots; locked in an Atlanta deli with sit-in demonstrators; and forced to sit in a scorching-hot courtroom gallery while covering the trial of two Klansmen for killing Lemuel Penn, a black Army officer.