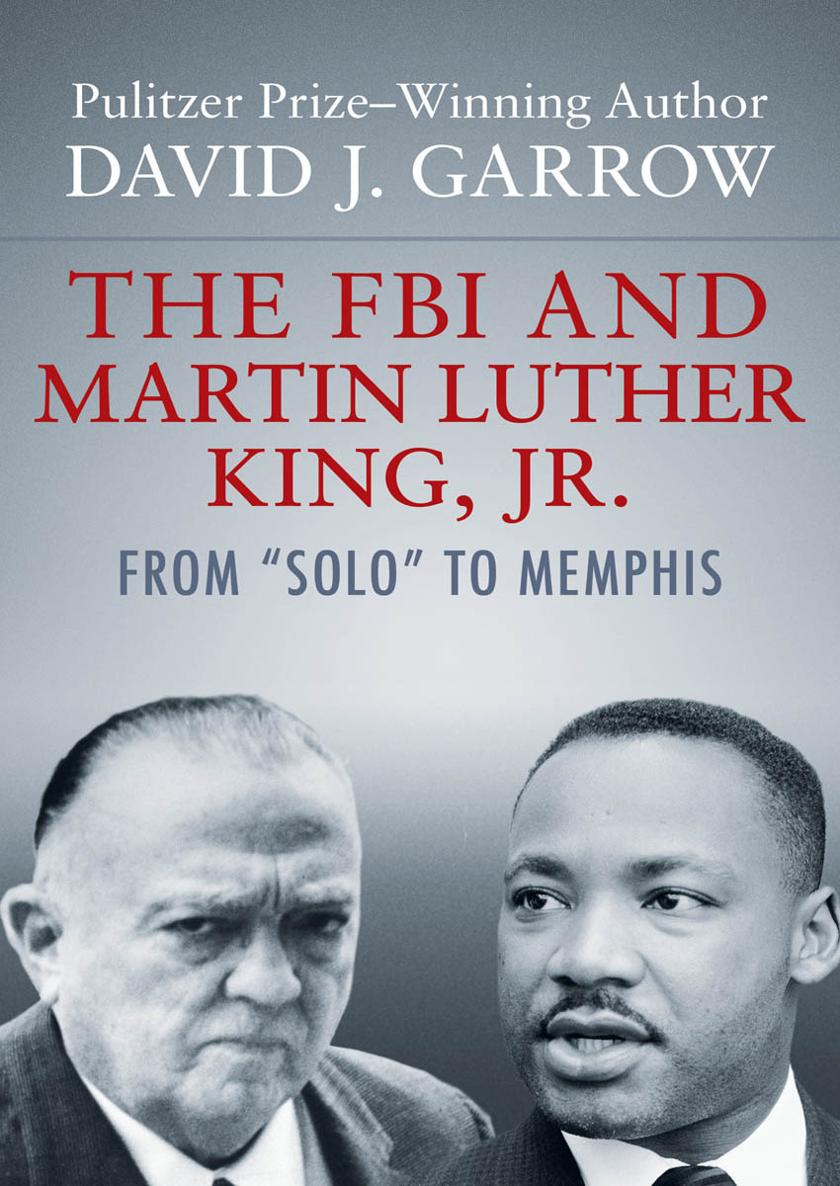

Preface

This book explains why the Federal Bureau of Investigation pursued Martin Luther King, Jr., throughout the 1960s. It argues that the Bureaus probe of King went through three different periods of development, and that distinctly dissimilar motives underlay the FBIs behavior in each of these phases. It further argues that the Bureaus conduct in the King investigation was indicative of more than just its attitude toward one man, and that a careful analysis of why the FBI went after King can point toward a broader understanding of why the FBI acted as it did toward a whole range of individuals and organizations.

This work began as part of a much larger study of Dr. Kings public career from 1955 to 1968. For that work, which remains in progress and is scheduled to appear in 1983, I examined reports produced by two well publicized inquiries into the Federal Bureau of Investigations activities concerning Dr. Kingthe 197576 review by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Activities, commonly known as the Church Committee,years before his death? Why would the United Statess major police agency devote so much energy and resources to an intense pursuit of one man and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference?

Unsatisfied and puzzled by the lack of attention to that question, I examined two other major studies of the Bureaus activities concerning Dr. King, those of the Justice Department in 197576 and 197677. While the latter of these, which reviewed both the FBI security probe of King and the Bureaus assassination investigation, was publicly available, Here again, however, I discovered that both teams of investigators had failed to appreciate the importance of asking that question, why?, and my disappointment with this blindness remained acute.

The value of pursuing that question was further impressed upon me when I first examined some of the FBIs own documents pertaining to the King case. Many of the most crucial items had crossed the desk of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover himself, and Hoover had retained copies of some of them in his personal Official and Confidential file on Dr. King. This file of Hoovers, along with several other O & C folders, was released in 1978 in response to an FOIA request filed by the Center for National Security Studies, and that sample of sensitive documents was a fascinating trove. Coupled with additional important items published by the House Assassinations Committee early in 1979, those O & C documents convinced me that that question of why the Bureau had pursued Dr. King so intensively was not only important to ask, but possible to answer. Thus I decided in mid-1979 to request all of the relevant FBI files on King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and to couple an analysis of that material with critical interviewing of those directly involved who were willing to talk.

Understanding the FBIs extensive and complicated filing system is no easy task. Quite probably no one outside the Bureau fully grasps its intricacies.end of 1979. While that estimate proved overly optimisticfor release actually began only in the summer of 1980it soon also became apparent that those two main files were only the tip of the iceberg.

First, FBI headquarters files actually contain only a part of the paperwork and documentation that a Bureau investigation generates. Most of the actual work, of course, takes place not at headquarters, but in Bureau field offices around the country. Only one-third or so of the material produced there is ever forwarded to Washington. The Bureau is very reluctant to process these voluminous field-office files for release under the Freedom of Information Act. To date I have received no assurance that my request for the Atlanta, New York, and Birmingham field-office files on King and SCLC will be processed anytime soon.

Second, the FOIA allows the Bureau to make major deletions in files that it does choose to release. Most deletions occur under two particular exemptions, one known as (b)(1), which is designed to remove classified information about the national defense or foreign policy, and the second called (b)(7)(d), which is aimed at protecting the identities of confidential sources, i.e., human informants. The Bureau makes liberal use of these two major exemptions, especially (b)(1), and much information that has absolutely no possible relationship to national defense or even the most inclusive conceptions of the widely abused idea of national security is deleted.

While the FOIA is seen as a dangerous and even un-American weapon by some, few would view the FOIA as any threat to the country if they had an opportunity to witness firsthand the way the Bureau and other agencies employ it. The FOIA is widely abused, but in exactly the opposite fashion from what its many detractors charge.

Deletions under the (b)(1) rubric are surely nettlesome for anyone seeking to obtain FBI files under the FOIA, but there are two even more serious deletion problems that plague the King and SCLC files. One is that most material gathered by the FBI on King and SCLC from mid-1966 to the time of Kings death came from one human informant. In a futile attempt to protect this persons identity the Bureau has adopted a policy, as it often does, of releasing none of the information furnished by that individual, under the theory that the content itself will indicate who supplied it. While this book reveals that mans identity and discusses his role in chapter 5, the Bureaus extensive deletions greatly inhibit a fully informed analysis of this mans behavior in the FBIs investigation of King and SCLC.

A second serious problem concerns the material that the FBI garnered from its extensive telephone wiretapping of Dr. Kings Atlanta home and SCLC headquarters between late 1963 and mid-1966. Though in theory this material would be eligible for release under the FOIA, all of the fruits of those wiretaps, along with the products of the many microphone surveillances or buggings of Dr. King in hotel rooms across the United States, were removed from the FBIs possession early in 1977 by an order from the Federal District Court in Washington. All FBI recordings, transcripts, logs, and quotations from both the bugs and the wiretaps on Kings home and the SCLC offices were transferred to the National Archives, where they are to remain sealed for fifty yearsuntil 2027.