Copyright 2013 by Andrew Blauner

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

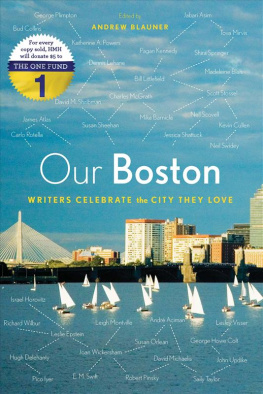

Our Boston : writers celebrate the city they love / edited by Andrew Blauner.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-544-26380-2

1. Boston (Mass.)Literary collections. 2. American literature21st century. I. Blauner, Andrew.

PS509.B665O96 2013

810.8'035874461dc23

2013027063

e ISBN 978-0-544-26388-8

v1.1013

Credit lines and permissions appear here .

For Mary Ann Leslie-Kelly

For Boston

Patriots Day

Restless that noble day, appeased by soft

Drinks and tobacco, littering the grass

While the flag snapped and brightened far aloft,

We waited for the marathon to pass,

We fathers and our little sons, let out

Of school and office to be put to shame.

Now from the street-side someone raised a shout,

And into view the first small runners came.

Dark in the glare, they seemed to thresh in place

Like preening flies upon a windowsill,

Yet gained and grew, and at a cruel pace

Swept by us on their way to Heartbreak Hill

Legs driving, fists at port, clenched faces, men,

And in amongst them, stamping on the sun,

Our champion Kelley, who would win again,

Rocked in his will, at rest within his run.

RICHARD WILBUR

Running Toward the Bombs

Kevin Cullen

D AWN BROKE CLEAR and clean over Boston on Patriots Day 2013, and Dan Linskey was up before the dawn.

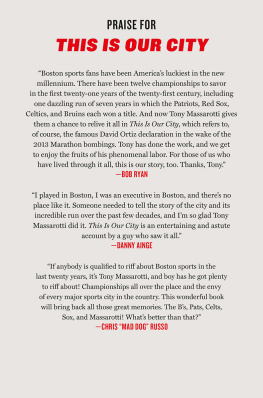

He walked down Boylston Street, near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, as he does every Patriots Day, because this is his town and this is his baby. Dan Linskey is the chief of the Boston Police Department. And he owns every big outdoor event in the city, from the raucous celebrations that follow the championships of Bostons sports teams, which seem to happen every other year, to the star-spangled festival when the Boston Pops serenades the city every Fourth of July.

His was not an idle walk. As chief of the department, Linskey had drawn up several disaster scenarios, and the reality is that in the post-9/11 world, the marathon, like every other outdoor event in Boston, was a target for terrorists.

Still, there was nothing on this sunny morning that led Linskey to believe it would be anything other than the day it usually is, the people lined along Boylston, five deep, cheering the runners on those last few hundred yards, toward the finish line at the Boston Public Library.

Patriots Day is a holiday in Boston recalling the shots fired at Concord and Lexington, just outside the city, when a bunch of farmers took on an empire and won. The traffic is light. Out of the corner of his eye, Dan Linskey spied a woman who had set up camp on the corner of the Ring Road, blocking it. The Ring Road was an access point for emergency vehicles to Boylston Street.

Maam, you cant stay here, Dan Linskey told the woman.

This being Boston, she gave it right back to him, informing him that she had got up early to stake out a prime spot on Boylston and she wasnt giving it up, no matter what he said.

Dan Linskey, a cop for twenty-seven years, a Marine before that, can be nice when he has to be. But he can also be firm. With this woman he was firm, and soon she had begrudgingly decamped to a place farther down Boylston. She was angry, furious actually. But in moving, at Dan Linskeys insistence, that woman unwittingly saved many lives.

Bill and Denise Richard told the kids the night before that they were heading into town from their Dorchester home to see the marathon. Their childrenHenry, nine, Martin, eight, and Jane, sevenwere excited. It was a family tradition, and like all family traditions, it was something cherished.

Bill and Denise were what some suburbanites would call homesteaders. From the 1970s right through the end of the twentieth century, many people had left Boston in what the demographers dubbed white flight. The Richards were the other side of the coin. They chose to live in the Ashmont section of Dorchester, which like a lot of neighborhoods in Bostons inner city had seen something of a decline in the second half of the twentieth century.

But the Richards were part and parcel of Ashmonts revitalization. They sent their kids to the local charter school. They, like others, saw things changing for the better when Chris Douglass, one of the citys premier restaurateurs, opened a high-end place, the Ashmont Grill, right in the middle of the neighborhood in 2005. And the Richards were prime movers in getting the state to invest heavily in rebuilding the Ashmont train and bus station. The Richards were among those who breathed new life into an old neighborhood, giving it endless possibilities.

The Richard kids were giddy with excitement, leaning against the metal barriers, watching the runners, who were different colors, like the flags of all the worlds nations lining the last portion of the marathon route.

Standing there, enraptured by the sights and sounds of people finishing the last steps of twenty-six miles, the cheering sustained, neither the Richards nor anyone else noticed as a nineteen-year-old Chechen kid named Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, wearing his baseball cap backward like many other kids in the crowd, approached from behind. Tsarnaev placed a backpack right behind eight-year-old Martin Richard, then continued to walk up Boylston Street.

They call the fire station Broadway, even though its in the South End, a mile away from the real Broadway in South Boston. It houses Engine 7 and Tower Ladder 17, and it is one of the busiest firehouses in the city.

On Patriots Day, as the runners passed the finish line on Boylston, the men from Engine 7 were around the corner, at an apartment building on Commonwealth Avenue, Bostons grandest boulevard. A group of college students had managed to put a gas grill on a narrow balcony to cook hamburgers and hot dogs while they partied Patriots Day away.

Two firefighters, Benny Upton and Sean OBrien, looked at each other, thinking that however smart these kids were to get into college, they couldnt be that smart.

Do you guys know how dangerous this is? Upton asked them.

The college kids were offering sheepish apologies when there was a boom from around the corner.

Upton, a former Marine who had done three combat tours, knew exactly what had happened.

Bomb! he yelled, and he and the men from Engine 7 and Tower Ladder 17 were soon running at full clip up Exeter Street, right into the belly of the beast. They had only just begun running when they heard a second explosion.

Jesus Christ, Tommy Hughes said to himself as he ran. Like Upton, he was a former Marine and could only imagine what lay around the corner on Boylston.

Actually, he later told me, he couldnt imagine it. It was worse than anything he saw in the military. Acrid smoke hung in the air and people lay scattered across the sidewalk. There were pools of blood, body parts. It was, at first, eerily quiet and the firefighters instinctively ran to the sides of the wounded.

Upton, like the other firefighters, knew it was terrorism, and they assumed they were running into secondary explosions, and perhaps a biochemical attack. But they, like their brother and sister police officers and paramedics and EMTs, ran toward the bombs anyway, because thats what they do.

Tommy Hughes was almost immediately faced with a Hobsons choice. Two children, one a boy, the other a girl, both missing a leg, lay on the sidewalk, like fish out of water, wriggling helplessly. Hughes reached down and picked up the boy, who was closer to him, but his guilt was assuaged immediately because another firefighter picked up the girl.

Next page