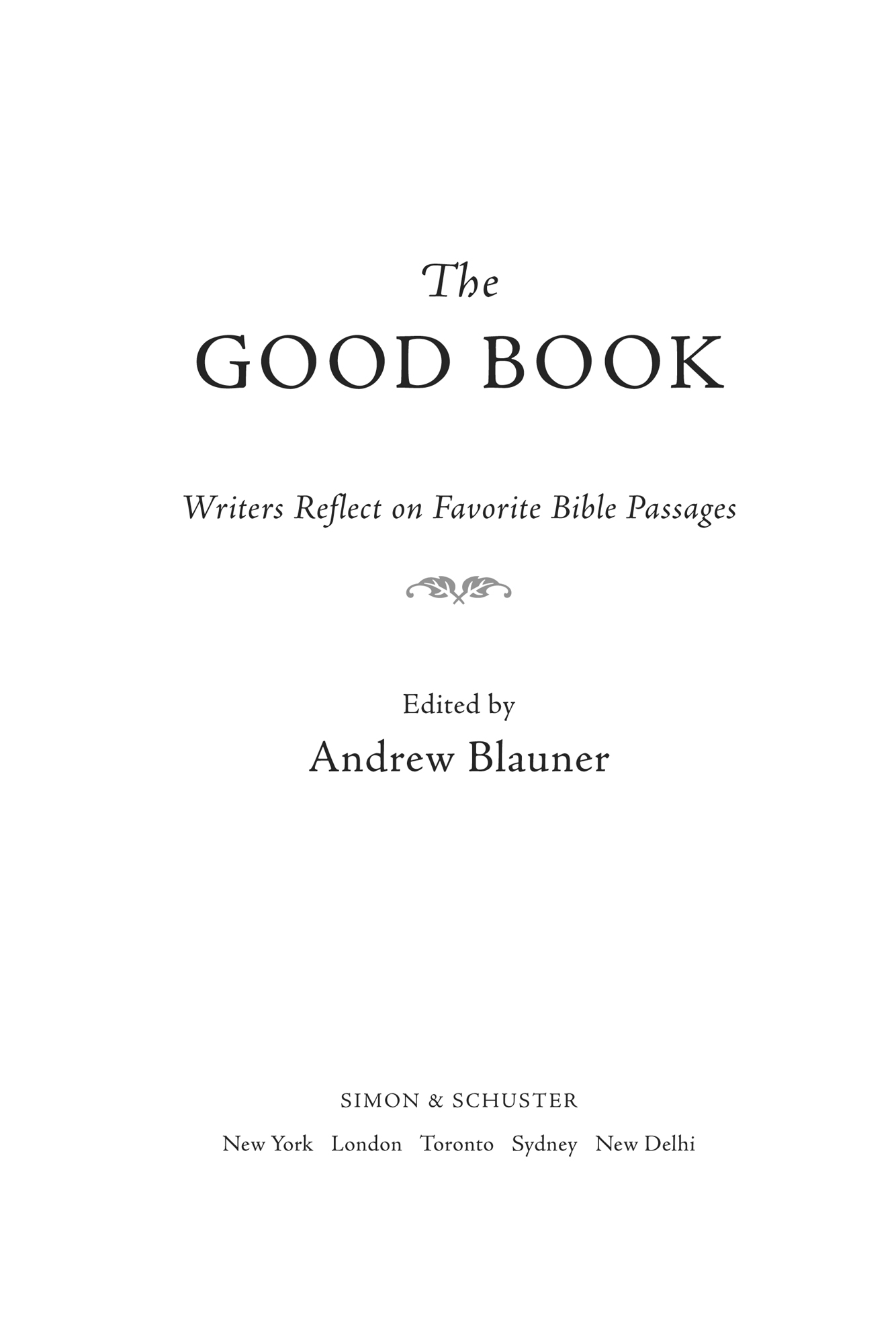

ALSO EDITED BY ANDREW BLAUNER

Our Boston: Writers Celebrate the City They Love

Central Park: An Anthology

Brothers: 26 Stories of Love and Rivalry

Coach: 25 Writers Reflect on People Who Made a Difference

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Compilation copyright 2015 by Andrew Blauner

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

Miracle, poem from Human Chain by Seamus Heaney, reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition November 2015

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Book design by Ellen R. Sasahara

Jacket design by Ren Julius Reyes

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

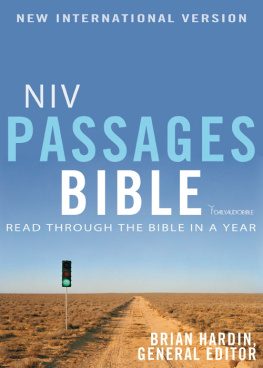

The good book : writers reflect on favorite Bible passages / edited by Andrew Blauner. First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition.

pagescm

1. Bible as literature.I. Blauner, Andrew, editor.

BS535.G662015

220.6dc232015010157

ISBN 978-1-4767-8996-5

ISBN 978-1-4767-8998-9 (ebook)

Contents

The Good Book:

An Introduction

Adam Gopnik

H ow shall we sing the Lords song in a strange land? And how should we read the Bible in a secular age? At a time when this odd, disjointed compilation of ancient Hebrew texts and later Greek texts has lost its claims to historical truth, or to supernatural revelation, it would seem to some that we might simply let it fade, read, until it becomes one more of those texts, like Galens medicine or the physics of Aristotle, that everyone knows once mattered but now are left quietly to sit on the shelf and wait for a scholar.

As history and revelation its stories have long ago fallen away; we know that almost nothing that happens in it actually happened, and that its miracles, large and small, are of the same kind and credibility as all the other miracles that crowd the worlds great granary of superstition. Only a handful of fundamentalistsgranted that in America that handful is sometimes more like an armful, and at times like a roomfulread it literally, and, though the noes may not always have it in raw numbers, the successive triumphs of critical reason mean that they have it in all educated circles. (Believers may cry elitism at this truthbut the simpler truth is that when the educated elite has rejected an idea its usually because theres something in the idea that resists education.)

And yet. The Bible remains an essential part of the education of what used to be called the well-furnished mind. Not to know it is not to know enough. Most of what we value in our art and architecture, our music and poetryBach and Chartres, Shakespeare and Milton, Giotto at the Arena Chapel and Blakes Job among his friendsis entangled with these old books and ancient texts: we enter Chartres and see the Tree of Jacob, and we need to know that this is the line of the inheritance of Jesus. We queue for hours to see the Sistine Ceiling, and our hearts stop at what Michelangelos hand has done all the quicker if we see the sublime text in our mind as we look at the picture with our eyesand God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also. We listen to Bachs St. John Passion, and it means nothing if we do not know what a passion was, and how this one horribly unfolded.

Though our search for the spiritual needs no help from the supernaturalit is fully accounted for by human sensibilitystill, it does need help. The philistinism of the new atheists, the meagerness of their aesthetic responses, is the one fair reproach against them; the human content of the art and music of the past too often seems duly appreciated by them, as a tiresome obligation, rather than really known and felt, as an irresistible temptation. The past dependency of our whole civilization on a scaffolding made from scripture is a low stile that they leap over lazily, with a shrug, rather than a high one, demanding a huge leap of, well, non-faith.

Yet some other part of its appeal lies beyond its history in art and architecture, lies rather in our daily breadour continuing need for guidance through the harsher perplexities of earthly existence. The Twenty-Third Psalm remains as stirring for those who take heart simply at its image of a shepherds care as it does for those who think the Lord exists to exercise it. No, modern people are drawn to faith while practicing doubt, as our ancestors confessed their doubts while practicing their faith. Each of us engages, casually or self-consciously, with the idea of faith and the fact of doubtand so there is a vein of modern literature, philosophical and poetic, that will always remain a chronicle of how we read the Bible. The shuttle between the arguments made by liberal doubt and the magnetic pull of the art made by belief is not one that can be avoided by thinking modern men and women, and it turns, always, to the question of scripture, and how its read. How do we reconcile the power of the prose and the passions describedthe wisdom of the Psalms and the beauty of the Song of Solomonwith the plainer but truer truths of a civilization of rational inquiry? That fugue of doubt and faith, experienced as argument and art, is the music of our lives.

But how do we do it? How, we may ask as we propose to embark upon reading, do we go on reading scripture in a secular time? There seems something dispiriting about merely reading for effect, or for pleasure. Some may recall that in Goldfinger, Bond carried his Walther PPK in a hollowed-out book called The Bible to Be Read as Literature. The mordant joke was that, once we read the Bible only for pleasure, we might as well use it to inflict the more glamorous kind of pain: after faith goes, nothing but vodka, bullets, and a void. If the Bible is to be read as literature, as something more than a joke, or an antiquarian oddity, how is it to be done?

As usual, to answer the question of what we should do, it is best to look at what we do do. There are, in place already, four pervasive methods or styles, shared by modern people, for reading the Bible (all illustrated, often overlapping and hybridized, in these pages).

There is first of all the aesthetic habit of readingwe read and dissect the books and verses of the Bible because they tell beautiful stories, stirring and shapely. We read the good book because it is a good book. We explore the stories because they are transfixing stories, dense and compelling. The beauty of the Song of Songs, or the nobility of the account of creation in Genesis, or the poetic hum of the Psalmsthese things are beautiful as poetic myths alone can be. That they were best translated into our own language in the highest period of English prose and verse, in Shakespeares rhythms and vocabularyconceivably with his hand at work, and certainly with hands near as good as hisonly makes them more seductive. (Even when more modern translations are not as good, they often echo the King James Version.) These are good tales and great poetry, and we need not worry about their sources any more than we worry about which level at that endless archaeological dig in Turkey is truly Troy. We read them not as myth but as fictionwe read them as we read all good stories, for their perplexities as much as for their obvious points.

Next page