Other books by Robert Hutchinson

Last Days of Henry VIII

Elizabeths Spymaster

Thomas Cromwell

House of Treason

Young Henry

The Spanish Armada

This book could not have been written without the tireless and enthusiastic support of my dear wife, who has shared with me the complexities of seventeenth-century Irish politics and the conspiracies against the crown and government of Charles II.

I am very grateful to Heather Rowland, Head of Library Collections, and Adrian James, Assistant Librarian, at the Society of Antiquaries of London; Kay Walters and her team at the Athenum Club library; the staff at the University of Sussex library at Falmer, East Sussex and the National Archives at Kew and in the Rare Books, Manuscripts and Humanities reading rooms at the British Library. My thanks are also due to the staff at the Bodleian Library; to my researchers Hilda McGauley of Records of Ireland for her assistance at the National Library of Ireland and especially to Denise A. Harman for her hard work at the Lancashire Record Office. Lastly, I am particularly grateful to Robert C. Woosnam-Savage, Curator of European Edged Weapons at the Royal Armouries, and to my good friend Philip J. Lankester, Curator Emeritus, for their very kind help with Colonel Bloods ballock daggers.

At Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Alan Samson has, as always, been encouraging and helpful, as has Lucinda McNeile, and I would like to record my gratitude to my meticulous editor Anne OBrien and to David Atkinson for compiling the index and to my agent Andrew Lownie. Any errors or omissions are entirely my responsibility.

Robert Hutchinson

West Sussex, 2015

So high was Bloods fame for sagacity and intrepidity... [he was believed] capable of undertaking anything his passion or interest dictated [no matter] how desperate or difficult.

Biographia Britannia, 174766.

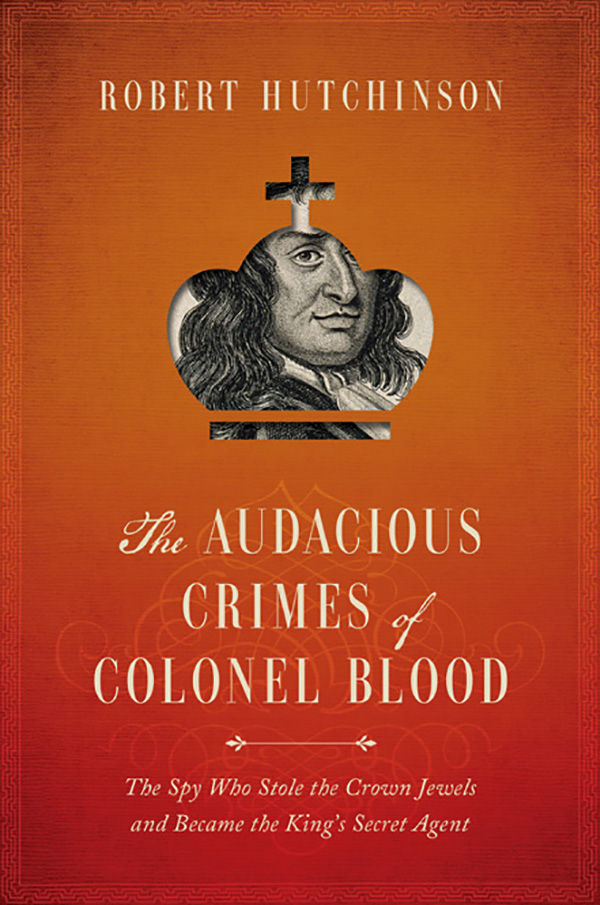

Colonel Thomas Blood is one of those mysterious and charismatic characters in British history whose breathtaking exploits underline the wisdom of the old maxim that truth can be stranger than fiction.

An attempted coup dtat in Ireland and his involvement in countless plots to assassinate Charles II and to overthrow the lawful government of England, Scotland and Ireland in the late seventeenth century won him widespread notoriety in the three kingdoms. Little wonder, then, that Charles IIs ministers publicly branded him the Father of all Treasons. With a substantial price on his head, dead or alive, Blood became a hunted man throughout the length and breadth of the British Isles.

But this extraordinary fugitive from justice was far from cowed by any hue and cry pursuing him in the dark, filthy alleyways and back lanes of London or Dublin. Paradoxically, the tighter the net was drawn around him, the more audacious this notorious traitor and incendiary became.

Bloods attempt to steal the Crown Jewels from within the protective high walls of the Tower of London in May 1671 propels him to the top of a very select group of bold outlaws who have preyed upon the riches of the English royal court down the years.

In the mid-fourteenth century, Adam the Leper cheekily snatched property belonging to Edward IIIs buxom and matronly queen, Philippa of Hainault.

Almost four centuries on, Blood was no mere thief, no matter how brazen his crime. He was an incorrigible adventurer who, not for the first time, eventually turned his coat to live a perilous existence as a government spy, or double agent, for Charles IIs secret service in their battle to counter both internal and external threats to the uncertain Stuart crown.

His skill at avoiding retribution was so adroit that when he finally went to meet his Maker, there was a prevalent belief that he had managed to cheat even the Grim Reaper himself. The alehouses of Westminster and Whitehall buzzed with stories that the old soldier had not died but was only up to his usual tricks. Was his demise just another of Bloods clever stratagems to fool his many powerful enemies at the royal court? Was death his ultimate cunning disguise?

Such was the full tide of rumour running across London that the government was forced to exhume Bloods body from his grave in Tothill Fields chapel to demonstrate publicly the mouldering truth. The colonels swollen and rotting cadaver was only identified at a grim inquest in Westminster by a witness recalling the inordinately large size of one of his thumbs.

His was a complex character, full of contradiction and inconsistency. He possessed strong nonconformist religious beliefs, pledging himself daily to be in serious consideration... of Christ and what he has done and not to be slothful in the works of ye lord. He claimed to shun wine, strong drink and any kind of excess in recreations or pomp or in apparel... quibbling or joking... all obscene and scurrilous talk.

Sometimes he erred from this straight-and-narrow godly path. Blood was also an arrogant, eccentric fantasist with a very persuasive manner, reinforced by buckets of Irish charm and armed with a neat turn of phrase that proved useful in a tight spot. That lyrical word blarney might have been created especially for him. And, in truth, his escapades, conducted under a multitude of aliases and assisted by a wardrobe packed full of disguises, left no swash unbuckled, no outrage untested, no crime too great to attempt. Many a daring man of action would resemble more a meek, pious Vatican altar boy by comparison.

Thomas Blood came from a family whose origins, appropriately, lay in a thirst for adventure. The Irish branch traces its origins to Edmund Blood, a minor member of the Tudor gentry, from the tiny hamlet of Makeney, near Duffield in Derbyshire, who sailed off to Ireland in 1595 as an ambitious twenty-seven-year-old cavalry captain seeking fame and fortune or, more bluntly, the simple plunder of war or the joyful sequestration of an enemys land and property.

He joined Queen Elizabeth Is army to fight in what became a bitter nine-year war against the Irish magnate Hugh ONeill and his allies, who sought, like so many others before and after, to finally end the alien English rule of the Emerald Isle. was appropriately christened Neptune.

Edmund quickly discovered that the discomforts of soldiering were not to his taste. He resigned his commission and acquired 200 acres (81 hectares) of land near Corofin in Co. Clare, along with nearby Kilnaboy Castle possibly through the influence of Inchiquin, his old travelling companion and later commanding officer, who already owned property in the area.

Extra income was opportunely earned by stopping ships sailing north along the Clare coast to Galway or south to Limerick and politely inviting their captains to hand over sizeable quantities of cash in return for the promise of a safe passage onwards. The presence of armed men in cutters, probably based at Lahinch in Liscannor Bay, was a persuasive reason to accept gracefully such imperative suggestions. Some may regard this traditional pastime as a protection racket, others as pure piracy but no one dared suggest there was any conflict with the sober Presbyterian religious beliefs that the Blood family had practised after arrival in Ireland.

Next page