Youre going to miss me when Im gone. Youre so terrible, with your double standards. You like to watch me, and then you like to say, Why dont you just die? Will you be happy when I die? When I die, there will never be another Qandeel Baloch. For a hundred years, you will not get another Qandeel. Youre going to miss me.

AUTHORS NOTE

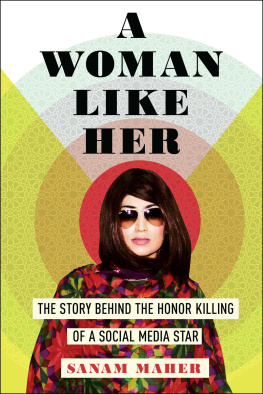

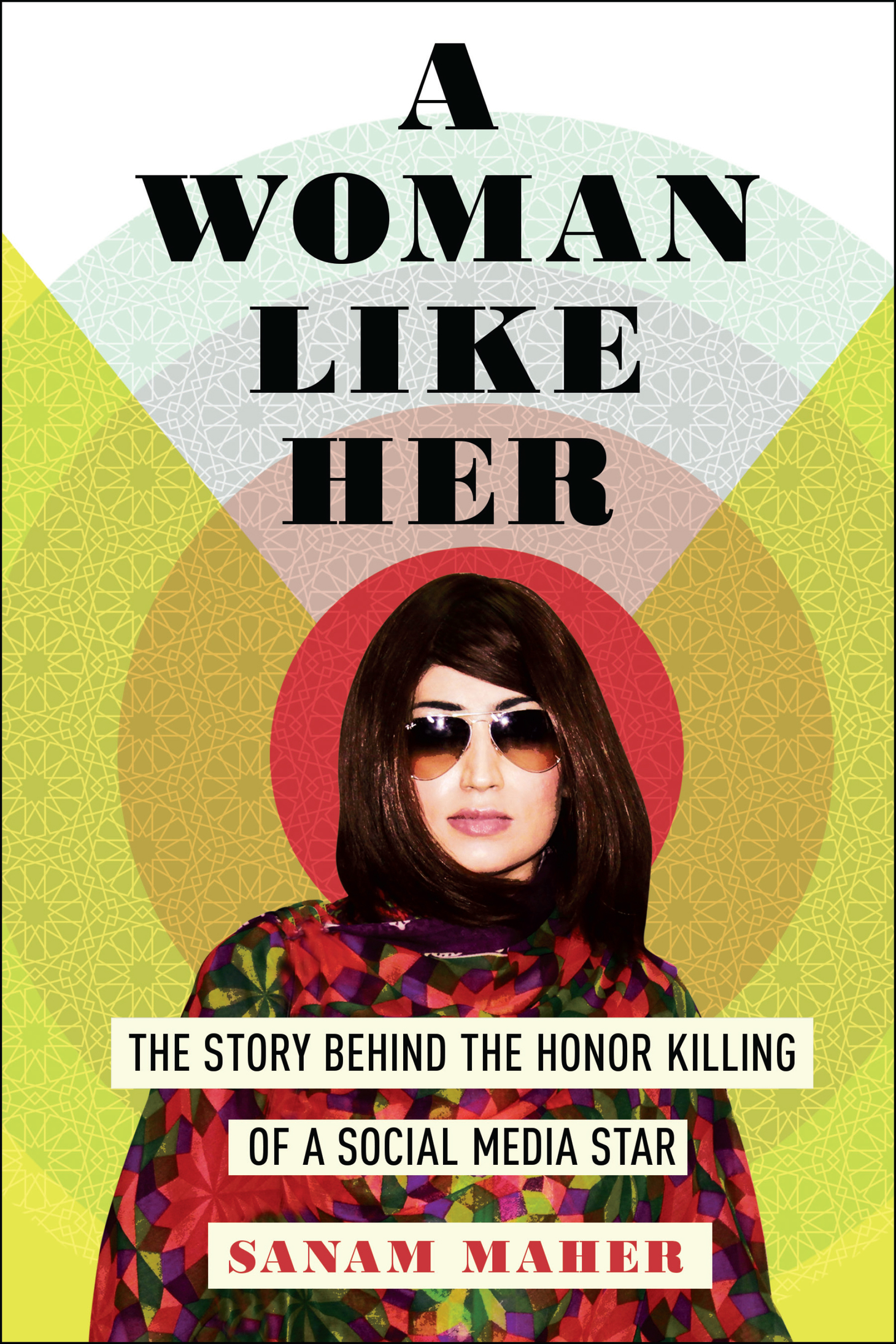

In February 2016, Issam Ahmed, a journalist from the international news agency Agence France-Presse, interviewed a twenty-five-year-old Pakistani woman for a story on how the countrys youth interacted with social media. Qandeel Baloch, the countrys first social media celebrity, had more than 700,000 followers on Facebook, 40,000 followers on Twitter, and a popular YouTube channel. Young people can communicate online in relative freedom, Ahmed reported. He described Baloch as a Kim Kardashian-type figure.

Ahmed was curious about whether Qandeels social media posts had any greater intent beyond gaining likes and followers. He thought her photographs and videos were funny, refreshing and cool, yet every time she posted something, she would receive a flood of abusive comments. So why did she keep going? It was gutsy, he thought. What did she want people to take away from what she was doing? When he first spoke with Qandeel, she was suspicious of these questions. It was the first time she had been interviewed for the foreign press, but more importantly, it was the first time that she was hearing that her social media activity had meaning.

Qandeel had caught Ahmeds attention after a video she posted on Facebook mocking a presidential warning not to celebrate Valentines Daydeemed a Western holidaywas viewed more than 800,000 times in less than two weeks. In the video, made on a cellphone as she lies in bed, Baloch wears a low-cut red dress, and her full lips are painted scarlet. The sheets match her outfit, and her dress rides up her legs to reveal her thighs. They can stop to people go out, she says in broken English, but they cant stop to people love. She says the same thing once more, this time in Urdu, with an exaggerated American accent, as though she is not used to speaking the language. No matter what they do, they cant stop people from loving. She whispers the message again: logon ko pyaar karnay se nahin rok saktay. These politicians are ghatiya (shameless) and idiots, she says with disgust. At least Imran Khan doesnt do this. Thats why I always support Imran Khan, she notes. She adds a personal message for the former cricketer turned prime minister: Imran, happy Valentines Day. I know youre alone and you dont have a Valentine. I dont either. Im also alone. And I dont want you to be my Valentine. I just want you to be mineForever.

The video shows us everything that Pakistanis lovedand loved to hateabout Qandeel: she played the coquette, dished out biting critiques of some of Pakistans most holy cows, and gave her heart away to politicians, actors, singers, and cricketers. We snickered at her accent and the way she spoke, and marveled at her gumption. She was the stuff of a hundred memes and the butt of our jokes.

Qandeels daily posts on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube were a mixed bagshe had a headache, she was bored, she had a song stuck in her head, she would try on a new dressand seen by thousands. Her posts went up at night, when Qandeel said she couldnt sleep, and they were forgotten by her viewers by the time morning came.

Until they became more risquby Pakistans standards, at least.

In March 2016, Qandeel uploaded a video that couldnt be swept aside so easily. She promised a striptease for her viewers if Pakistans cricket team won an upcoming match against India. For many of her fans, Qandeel had gone too far. Before you post these sort of videos think about your religion and your familythis is too much, one viewer commented. Others were not so polite. Please shoot her wherever you find her, wrote one user. You slut, if you love getting naked why dont you go sit in a brothel? asked a female Facebook user. Have some shame. I dont know what kind of family you come from, are they so dishonourable?

Four months later, she was dead. Her brother Waseem confessed to strangling her in their family home, in what would be described as an honour killinga murder to restore the respect and honour he believed Qandeels behaviour online robbed him of. You know what she was doing on Facebook, Waseem said when he was arrested and asked why he murdered her. She was twenty-six years old.

In the days after her death, many Pakistanis expressed happiness that Qandeel had been punished for behaving the way that she did. When he was asked about Qandeels murder, the leader of one of the largest religio-political groups in Pakistan, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, stated, We are Muslims and Pakistan has been made in the name of Islamshamelessness and exhibitionism are a scourge in our society, spread through women like her. I saw acquaintances in my own social media feeds having arguments about whether what had happened was right or wrong, whether Qandeel deserved what had been done to her. On social media, many women who condemned the murder or confessed that they had been fans of Qandeel faced a torrent of abusesome temporarily shut down their Facebook or Twitter accounts after receiving threats. Offline, many of the men and women I knew condemned Qandeels death but then, in the next breath, followed their statements with but if you think about it

In the year before Qandeel was murdered, 933 women and men were killed for honour in Pakistan, according to the countrys Federal Ministry of Law. Those are only the number of cases that were reported by friends and familiesmany honour crimes are not reported or covered up as a family can collude to protect one of their own. The victims are often believed to have broken a code that their community or family lives by, and their crimes can include anything from chatting with a member of the opposite sex on a cell phone or marrying someone of their own free will rather than having a marriage arranged by their parents.

The average Pakistani would find it challenging to recognize the faces or remember the names of any of these men and women. Their stories and our dismay at yet another killing fade with the newsprint from our fingers as we read about them.

But Qandeel was different. Her murder was splashed across the front page of every newspaper. She had appeared in our social media feeds every day, her videos nestled among photographs, status updates, or tweets by our friends and family. Whether we loved, loathed, or ignored her, it was difficult to turn away from the image of her shrouded remains, her hands and feet covered in henna by her mothera ritual from Shah Sadar Din, the village she was born and then buried in, that declares that this woman left the world with honour. Her family did not close ranks around their son and brother, the murderer. Even in death, Qandeel was exceptional, it seemed.