ACKNOWLEDGgMENTS

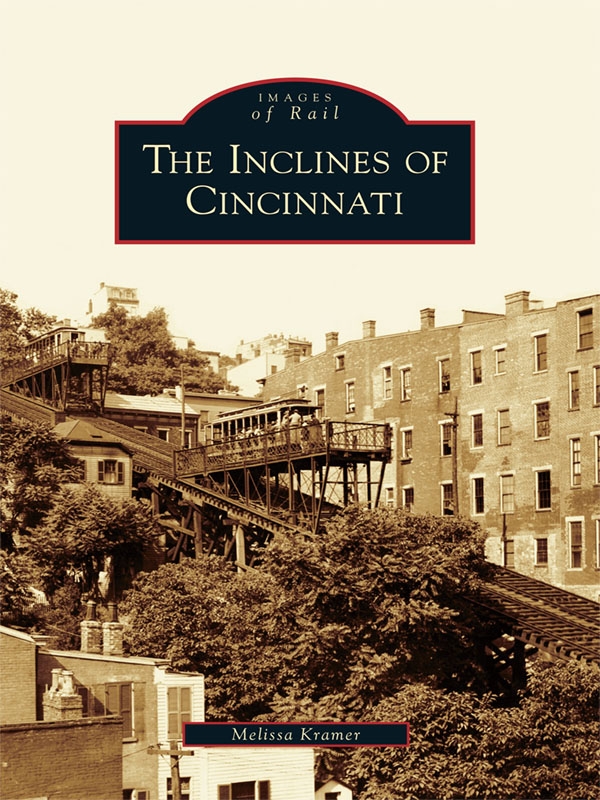

I would like to express my appreciation to the Cincinnati Railbuffs, who gather twice a month to discuss the history of rail, for welcoming me into their group. As true buffs, many of them are collectors of photographs, journals, and other memorabilia from the age when trains rather than automobiles were the preferred method of transportation. In particular, I thank Phil Lind, who provided the majority of photographs for this project. I cannot thank him enough for his generous accommodation to my requests for information and photographs. His considerable knowledge of the Cincinnati Street Railway and his passion for the history of Cincinnati made him a credible reference and an invaluable resource. I also want to thank Kevin Grace, Tom White, Earl Clark, Bill Van Doreen, Dan Finfrock, Fred Bauer, Bill Myers, Alvin Wulfekuhl, and Larry Fobiano. John H. White Jr., who wrote the beautiful and comprehensive coffee-table book about Cincinnatis inclines Cincinnati: City of Seven Hills and Five Inclines , contributed photographs and historic background and proofread this book for me.

I would like to thank my friend Jerry Seiter, another Cincinnati Railbuff, for introducing me to the group. Jon Miller, the librarian at the Cincinnati Historical Transit Association, has generously loaned materials and photographs from the files of the Mount Adams and Bellevue Inclines. Valda Moore and Richard Jones at the Price Hill Historic Society have been very generous with photographs and information. Melissa Basilone, my editor, has been a pleasure to work with. Elizabeth Meyer and Sarah Maguire at the University of Cincinnati DAAP Library offered their technical expertise. Elissa Sonnenberg, my mentor and academic advisor at the University of Cincinnati, has been a good source of guidance. Sometimes it has been difficult to get an accurate reconstruction of the age of the inclines, since accounts can contradict each other. John Brolley, my history professor, taught me how to search out credible sources.

My father Jerrys love of words and history was infectious. From an early age, he described for me the people and events connected with the bridges, buildings, and streets of Covington and Cincinnati. From him I learned that every structure has a story.

My daughter Dana offered help when I needed it the most, sorting newspaper articles and photographs. She brought her own enthusiasm to the project, and her passion for history encouraged me. My son Zachary contributed in his own way by allowing me to be half a mom. He developed a preference for frozen pizza, which allowed me to spend more time on the book.

Most of all, to my husband Dale, thank you for always believing in me.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

CINCINNATI HEADS FOR THE HILLS

Looking up at the lift of the Mount Adams Incline, this photograph was probably taken in the 1940s. (Courtesy of Phil Lind.)

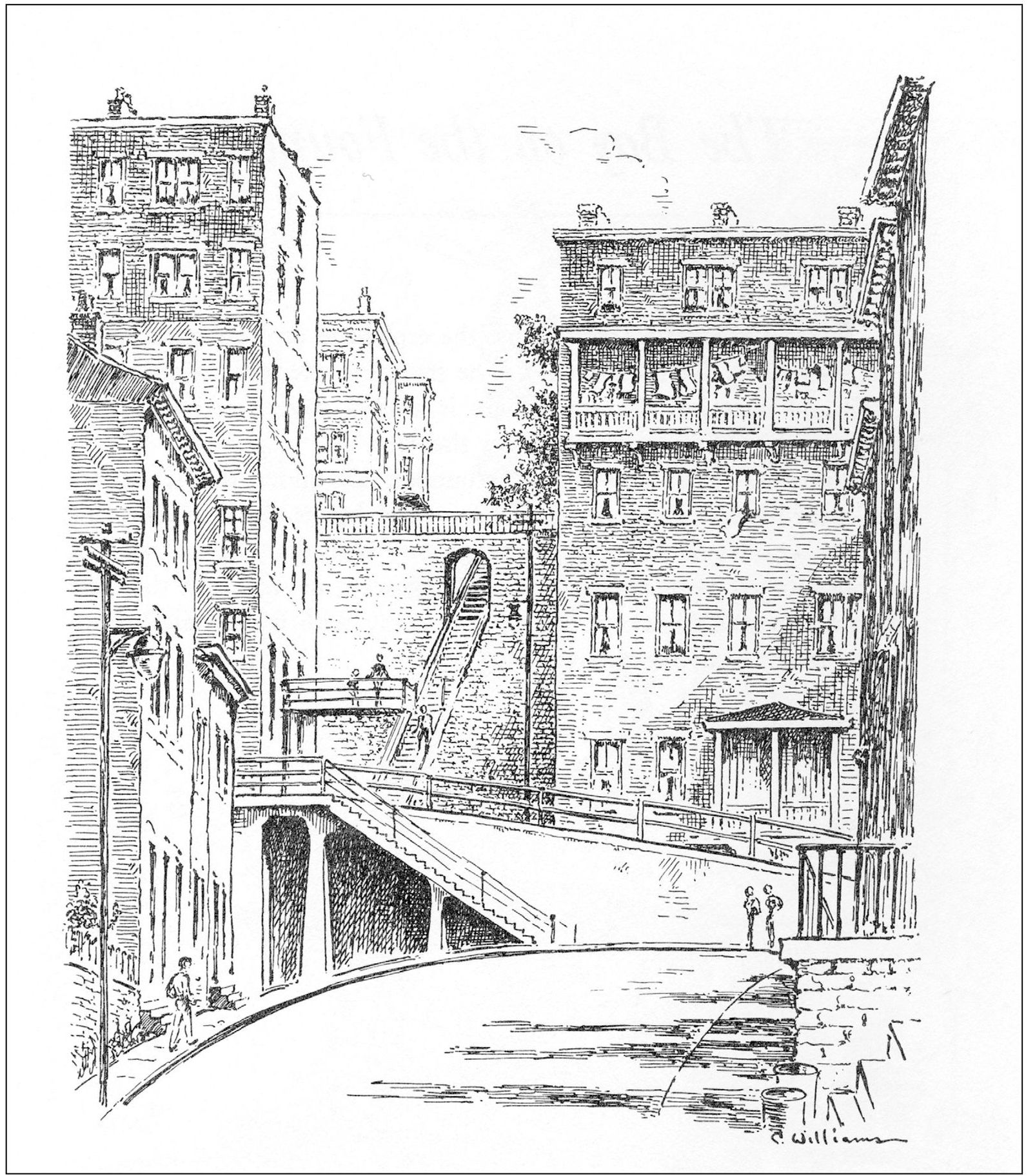

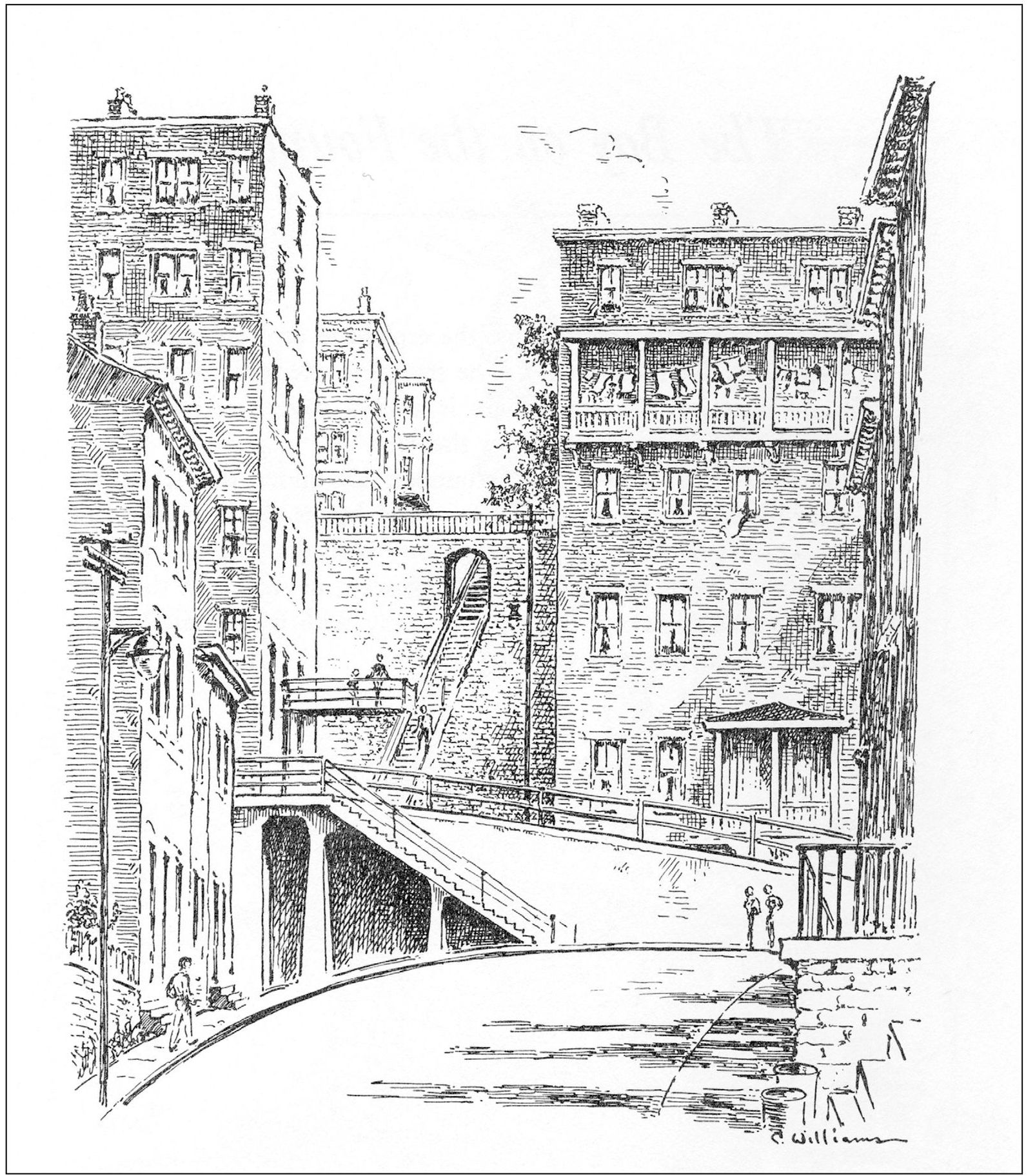

The early Cincinnatians, determined to conquer the difficult terrain, simply built steps into the hillside when the ground became too steep to lay a road. The grid of the city disintegrates at the foot of the hills where steps between the buildings disappear into the dense foliage, cutting into the hillside under a canopy of trees and emerging once again at the summit. Following the path of least resistance, they twist and turn for no apparent reason. The climber leaves one world and, upon passing through an opening or turning a corner, enters another. Often balconies overlook the steep, serpentine streets, as in this view of the top of Sycamore Street in Mount Auburn. Homes that appeared to be two stories at street level were actually six or more stories when viewed from behind, with the ground floor opening onto an entirely different neighborhood. The whole effect was like that of a medieval kingdom. There are nearly 400 sets of hillside steps in Cincinnati, many of which are left over from the days before the inclines. This sketch is by Caroline Williams.

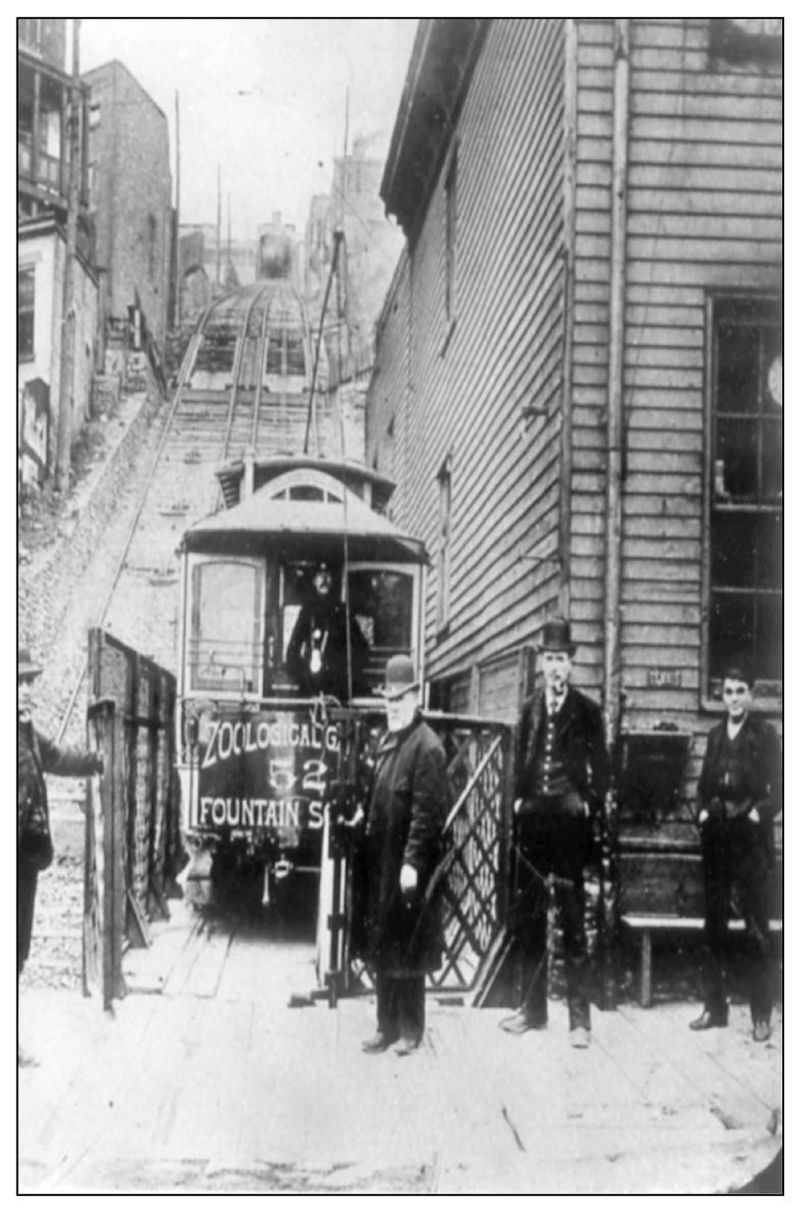

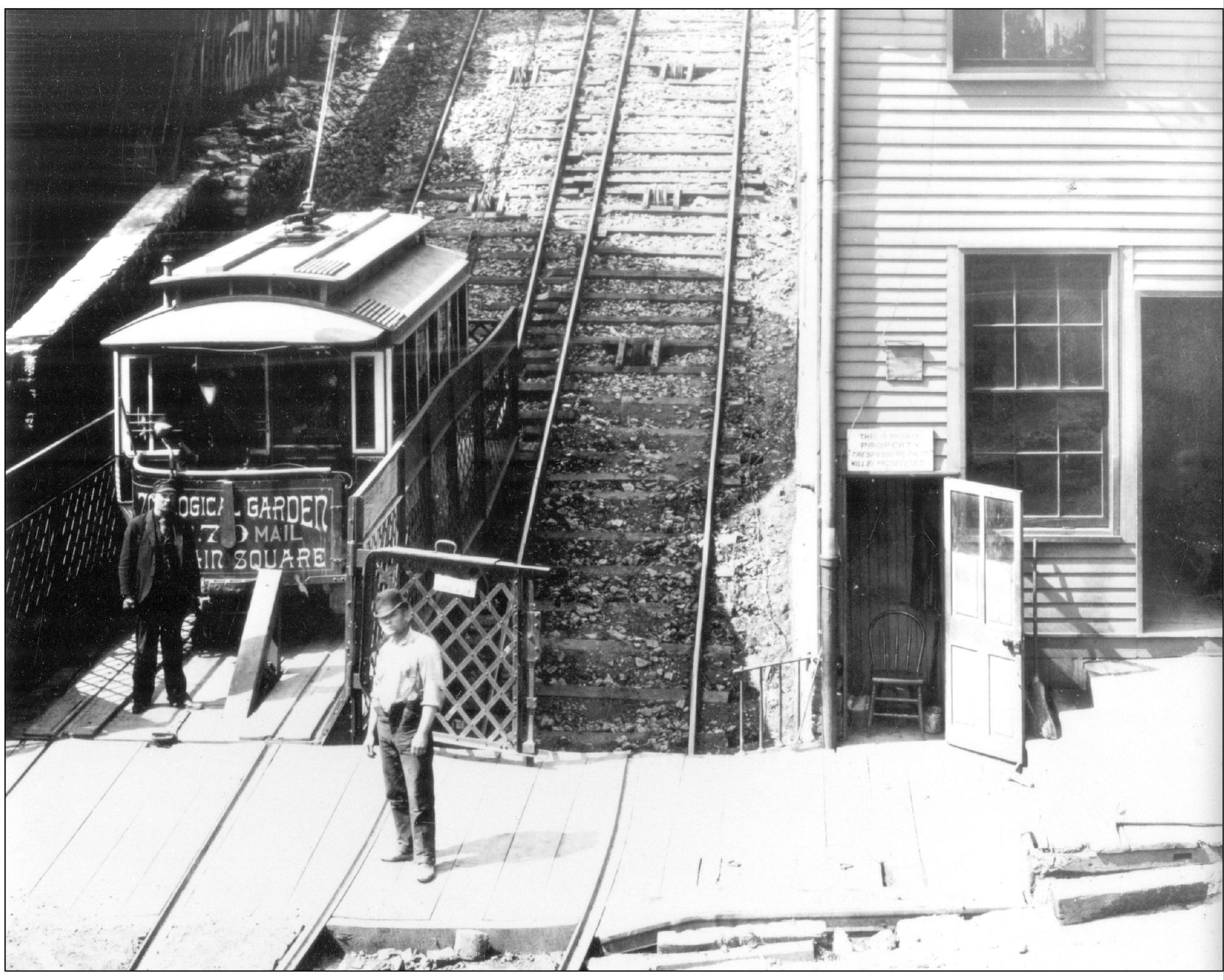

Thousands of people lined up to ride the citys first incline, which opened on May 12, 1872. This early photograph shows James M. Dougherty, supervisor of the plane, holding the gate while a conductor looks on from inside the streetcar. (Courtesy of Phil Lind.)

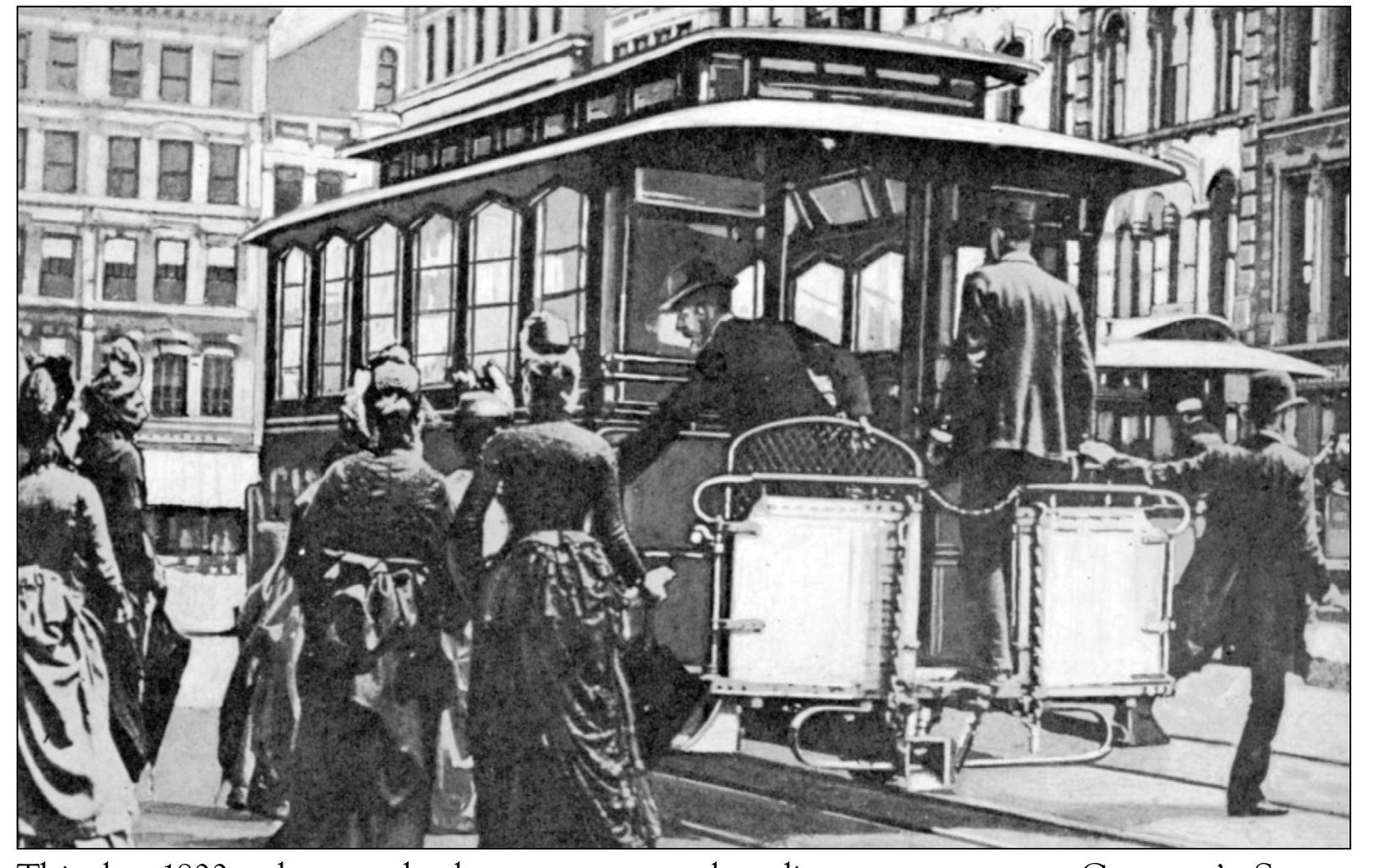

This late-1800s photograph shows passengers boarding a streetcar at Governors Square at Fifth and Main Streets. The line, which carried passengers from Fountain Square to the Cincinnati Zoo via the Mount Auburn Incline, was electrified in 1889. Governors Square continues to be an important hub for Cincinnatis public transportation system.

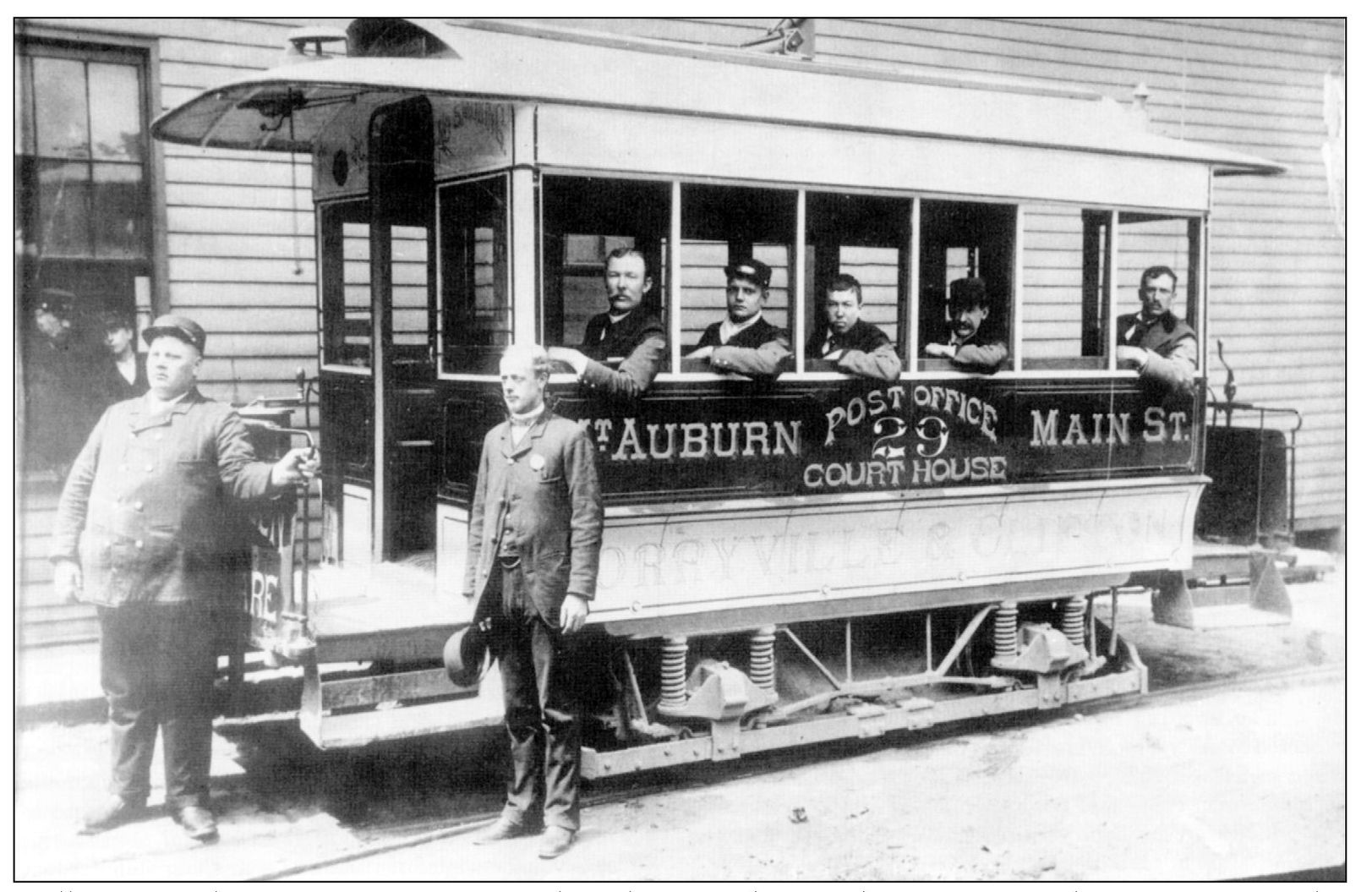

William Nagel, motorman, poses for this photograph outside a Mount Auburn streetcar. The other gentlemen are most likely associates of the Cincinnati Inclined Plane Company. (Courtesy of Earl Clark.)

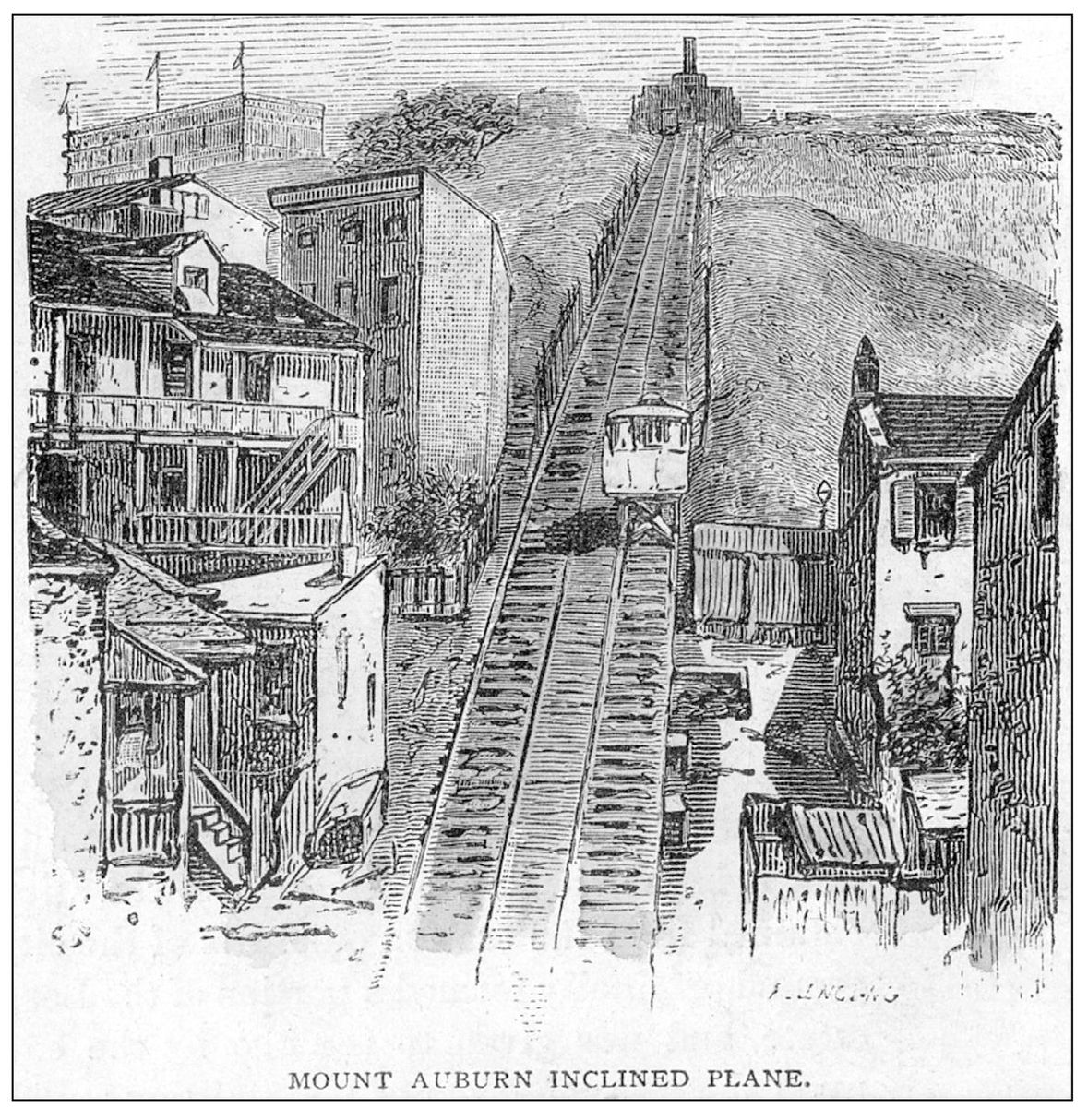

The hump of the Mount Auburn, or Main Street Incline, can be seen in this early illustration. This was the only incline that had a change in grade. The upper station was located in what is now Jackson Hill Park, just west of Auburn Avenue. (Courtesy of Bill Van Doreen.)

In 1878, the plane was rebuilt. The fixed cabs were converted to open platforms so that streetcars could be carried as well as passengers. The hump was somewhat straightened, and the track gauge was increased. Heavier engines, duplicate throttles, and reversing mechanisms were introduced. Three days after the Mount Auburn plane reopened, a pending lawsuit against the Cincinnati Inclined Plane Company was settled in favor of the plaintiff, the telephone company. Judge William Howard Taft upheld the claim that the trolley wires interfered with the phone service in Mount Auburn. Cincinnati streetcars had to convert to a double-wire system. This was a disappointment to the industry, since the single-wire system was the most economical. The Ohio Supreme Court reversed the decision the next year due to new evidence that the tracks, if properly bonded, could carry the ground current without affecting other electrical systems. (Courtesy of Earl Clark.)