Table of Contents

PENGUIN

CLASSICS TALES OF SOLDIERS AND CIVILIANS AND OTHER STORIES

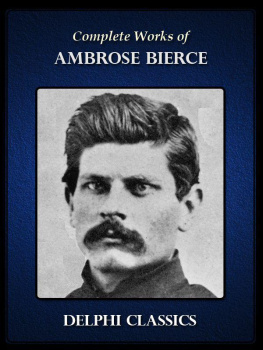

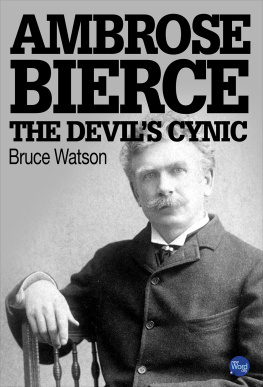

Ambrose Bierce was born in Miegs County, Ohio, in 1842, but he grew up in northern Indiana. Bierce briefly attended the Kentucky Military Institute, where he apparently studied surveying and mapmaking. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted as a private in the Indiana Ninth Brigade and eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant and served as regimental cartographer. He was present at some of the fiercest battles in the warShiloh, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, Picketts Mill, and othersand his war experience later provided the background for his most important war stories and for several autobiographical essays and sketches. After the war, he served as an aide for the Treasury Department in Alabama and later joined a fact finding expedition to the west. Eventually, he settled in San Francisco, and it was there he committed himself to the literary profession. He was a columnist and editor for various newspapers, including William Randolph Hearsts San Francisco Examiner. In 1871 he traveled with his wife to England and remained there for three years, writing for the British periodicals Figaro and Fun; his first three books were published in England. After he returned to California, Bierce continued to work as a journalist, but, particularly in the 1880s, he also devoted much of creative energy to writing short fiction. He published his collection of war fiction, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians, in 1892, and a volume of tales of the supernatural, Can Such Things Be?, in 1893. He also continued to work on his wry and sardonic definitions and collected them in his notorious The Devils Dictionary (1911). Bierces lacerating wit and devilish satire earned him the epithet Bitter Bierce. After 1899, Bierce lived in the East, and the last years of his life were largely devoted to preparing a handsome twelve volume set of his Collected Works (1902-12). That work complete, he revisited the battle sites of his youth and then traveled westward to El Paso. In December, 1913, he entered Mexico, presumably to accompany Pancho Villas army. He was never heard from again.

Tom Quirk is Professor of English at the University of Missouri- Columbia. He has written on several American authors, including Hawthorne, Poe, Melville, Twain, Wallace Stevens, Jean Toomer, Willa Cather, Joyce Carol Oates, Langston Hughes, and others. He is the author of Melvilles Confidence Man, Bergson and American Culture, Coming to Grips with Huckleberry Finn, and Mark Twain: A Study of the Short Fiction. He is the editor or co-editor of several books, including Writing the American Classics, American Realism and the Canon, Mark Twain: Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches, Biographies of Books, and The Viking Portable American Realism Reader.

INTRODUCTION

Herman Melville once complained that he would likely be known to posterity, if at all, as the man who had lived among cannibals. The substance and interest of his fiction insured him against such a fate. Ambrose Bierce has not been so fortunate. He is popularly known as the man who in old age walked into Mexico to accompany Pancho Villas army and was never heard from again, only incidentally known as the author of The Devils Dictionary and several exquisite short stories, and hardly known at all as a prolific writer whose collected works filled twelve substantial volumes. His final, and presumably fatal, gesture is romantic, I suppose, but it is also absurd. Besides, no one really knows where and how Bierce died. He might well have been engineering one last literary hoax; some scholars think so, and he was capable of such deception. The mystery of his last days is at least vividly obscure, but it has tended to eclipse the steadier certainties of the life he did lead.

The final image of him is ridiculous; he becomes something of an inverted Don Quixotea seventy-one-year-old asthmatic huffing and puffing through the Mexican deserts chasing after an army whose politics, if he ever considered them, he would have deplored, more intent on putting himself in harms way than tilting at wind-mills, to be sure, but perversely idealistic nonetheless. But Ambrose Bierce was not a ridiculous man, and the life he lived was more interesting and more substantial than its flamboyant and perhaps imagined conclusion. Though his fiction is not autobiographical in the way that Melvilles is, Bierces actual life does shed light on the themes and techniques of his imaginative writing. For that reason, it is worthwhile to linger over his biography before commenting on the achievement of his short fiction.

It was Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman who observed that War is Hell. Ambrose Bierce, who had seen much of the same war and often closer at hand than Sherman himself, defined the subject somewhat differently in The Devils Dictionary: War, n. A by-product of the arts of peace. The most menacing political condition is a period of international amity.... War loves to come like a thief in the night; professions of eternal amity provide the night. The authority of Shermans remark, we must suppose, derives from sad experience. Bierces is founded on the jaundiced coupling of abstractions uttered in a tone of weary urbanity and says a great deal more about the persona of the cynical lexicographer than it does about war or peace. This is to be expected of a man who has acquired (among other sinister sobriquets) the title Bitter Bierce.

Despite ample and fine biographical treatment of the man, Ambrose Gwinett Bierce remains, and will perhaps always remain, something of a mystery. It is not at all clear, at any rate, how much of his supposed bitterness was temperamental and how much contrived, and it is easy to overestimate the depth of his resentment. We know, for example, that, apart from his devotion to his brother Albert, Ambrose was not particularly attached to or even fond of his family. We know as well that in his Collected Works he reserved a section of one volume for stories gathered together under the title The Parenticide Club. Whether these two facts, taken together, make a third is less certain. Judging from the tone of the two stories from that section and included in this volume (My Favorite Murder and Oil of Dog), the thought of parenticide provided the occasion for tall tale humor and grisly fun and nothing more. And as the reader will soon discover, much of the shock and affecting pathos of his serious short fiction derives from the loss of some family membera wife, a twin brother, a father, a mother. Bierce knew how to play to his readers sensitivities, even though he did not necessarily share them himself.

Though the narrator of My Favorite Murder is accused of murdering his mother, his legal defense is that that crime pales in comparison with the way he murdered his uncle. This is purely antic fiction, and we know, as yet another fact, that Ambrose preferred his successful and relatively worldly uncle Lucius, to his pious and bookish father, Marcus, and certainly bore his uncle no ill will. Lucius Versus Bierce had come west to Ohio from Connecticut in 1815, and his younger brother Marcus had followed him a few years later. He had almost immediately embarked on plans for self-improvement, adventure, and self-advancement. He participated in the illegal Patriots War to rescue Canada from British domination and thereafter was known as General Bierce. He escaped conviction for violating U.S. neutrality laws and, in fact, was eventually elected the mayor of Akron.

CLASSICS TALES OF SOLDIERS AND CIVILIANS AND OTHER STORIES

CLASSICS TALES OF SOLDIERS AND CIVILIANS AND OTHER STORIES