Dial Books for Young Readers

Penguin Young Readers Group

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

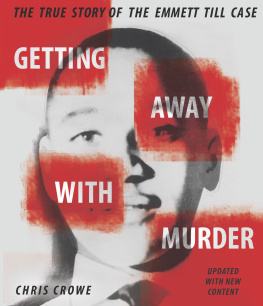

Copyright 2003, 2018 by Chris Crowe

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

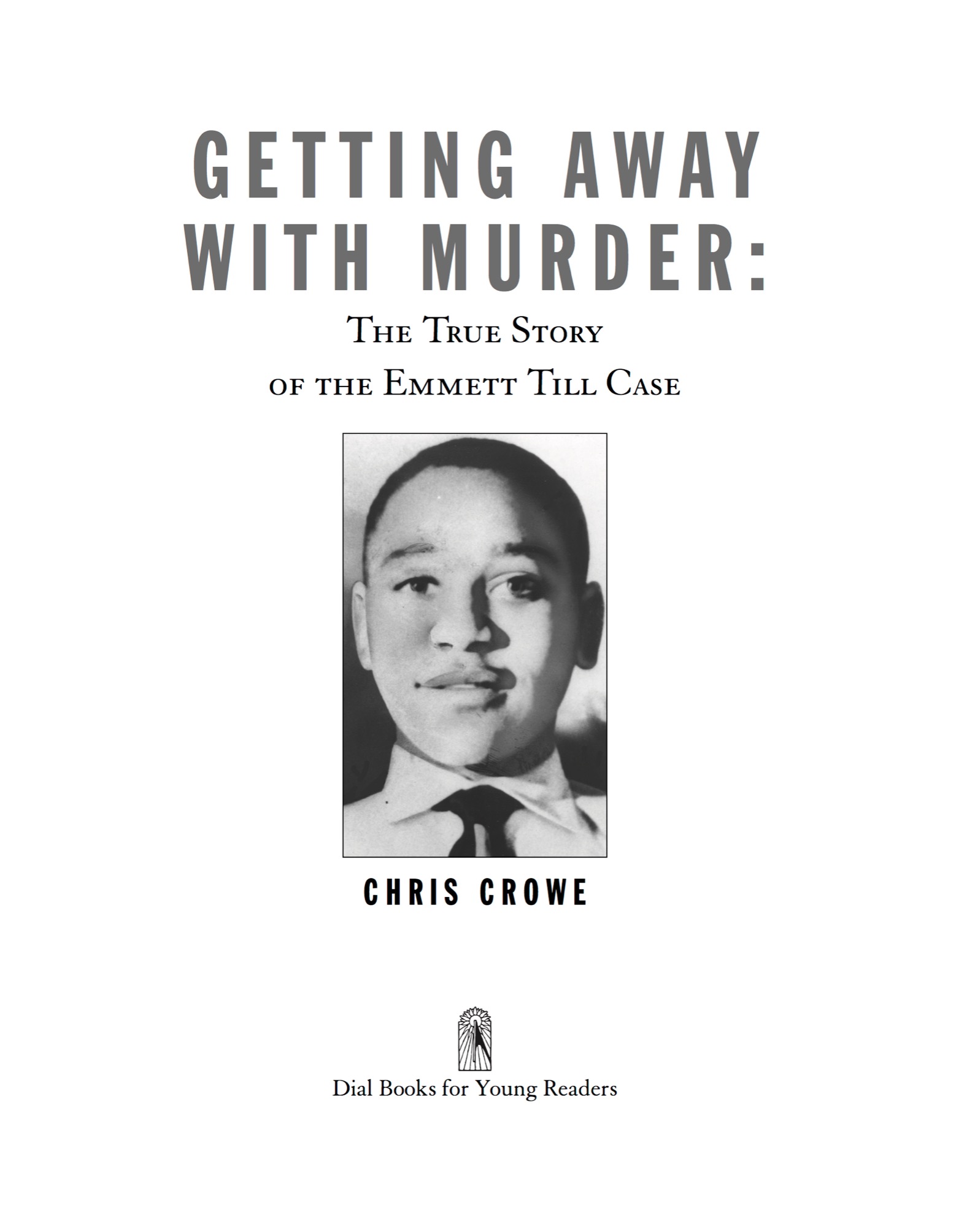

Crowe, Chris.

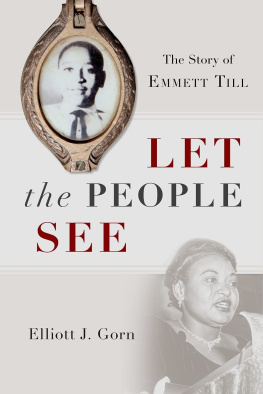

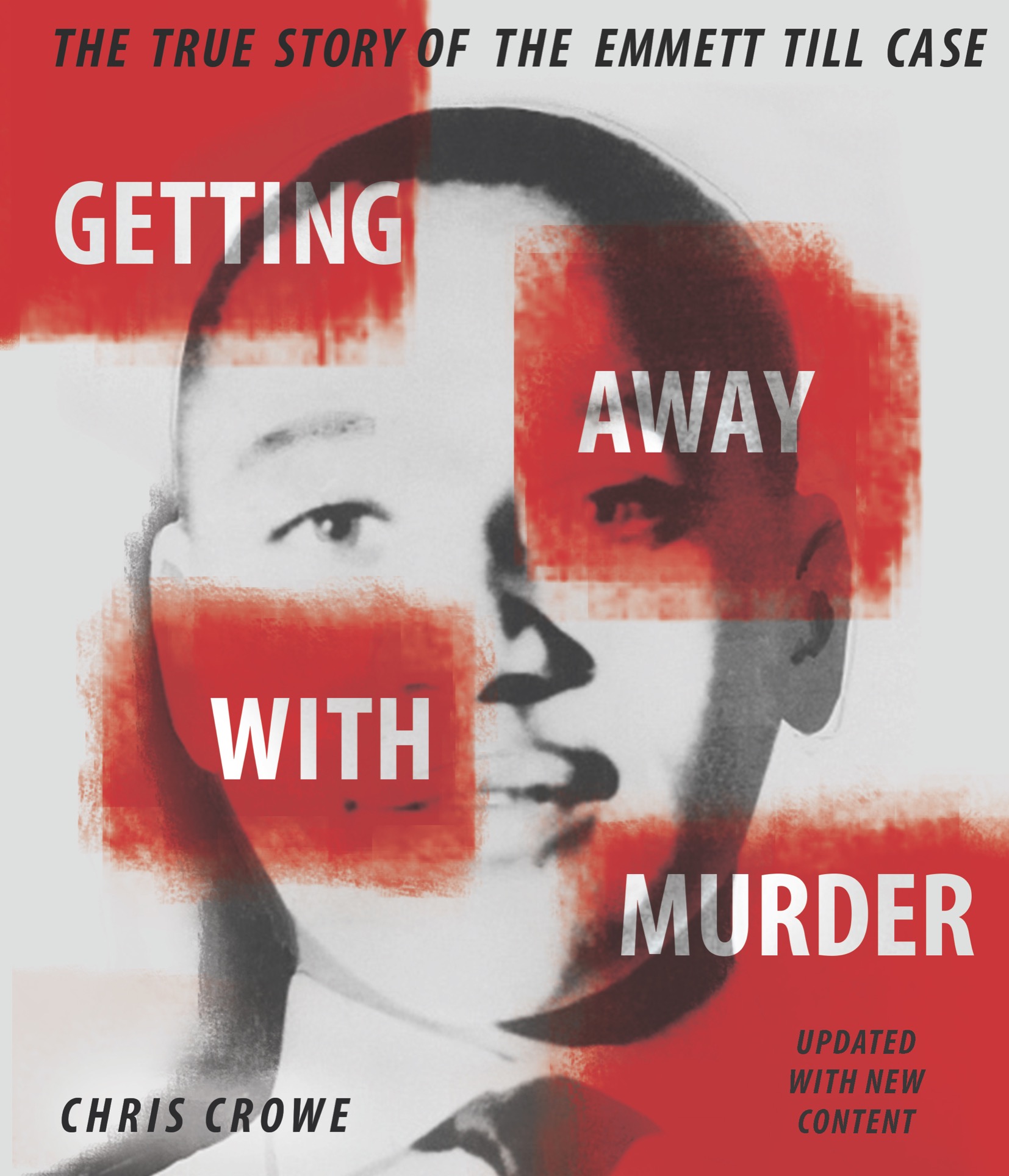

Getting away with murder : the True Story of the Emmett Till case / Chris Crowe.

Second edition. | New York, NY : Dial Books, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017033249 | ISBN 9780803728042 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Till, Emmett, 19411955Juvenile literature. | MississippiRace relationsJuvenile literature. | LynchingMississippiHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | African AmericansCrimes againstMississippiHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | African American teenage boysMississippiBiographyJuvenile literature. | RacismMississippiHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | Trials (Murder)MississippiJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC F350.N4 C76 2018 | DDC 364.15/2309762dc23

Photo credits:

Alan Karchmer/ NMAAHC: page

AP Images: pages

Bettmann/Getty: pages

Franklin McMahon/Getty: page

Ira Bostic/Shutterstock.com: page

Scott Olson/Getty: page

The Chicago Defender : page

The Commercial Appeal , Memphis, TN: pages

The Kansas City Star /McClatchy: page

Library of Congress: pages

New Story On Murder Of Till reprinted with permission of the Associated Press.

Quotation from For Us, The Living 1967 by Myrlie Evers-Williams and William Peters.

Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Cover design by Jessica Jenkins

Cover photo courtesy of Getty Images

Version_3

T ABLE OF C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have helped me complete this book, and I offer my sincere thanks for their support and cooperation: the student employees at BYUs Interlibrary Loan Office; Emmett Tills mother, Mamie Till Mobley; computer guru Joseph Palmer; researchers Shauna Barnes Belknap, Lisa Hale, Christina Youngberg, and Brooke Anderson; the staffs at the Library of Congress, the Bettman/Getty Photo Archives, AP Images, Time/Life Photo Archives, The Chicago Defender, and the BYU English Department. Special thanks to Claude Jones of The Commercial Appeal in Memphis for his generous cooperation in providing trial photographs. At Phyllis Fogelman Books, I am grateful to designer Kimi Weart and to associate editor Rebecca Waugh for their help in developing this book. Without the patience, insight, and support of Phyllis Fogelman, this project never would have been finished; I thank her for giving me the opportunity to tell the story of Emmett Till. My thanks also go to Mildred D. Taylor, an awe-inspiring writer, who first sent me in search of Emmett. My good friends Carol Lynch Williams and Jesse Crisler, both of whom are talented writers and readers, provided steady support and feedback throughout this project. My agent, Patricia J. Campbell, gave me the courage to tackle this book and opened just the right doors to get it published. Finally, to my wife, Elizabeth, and my daughters, Carrie and Joanne, thank you for listening to so many awful stories from 1955 and for giving me the kind of feedback and encouragement I so desperately needed. Special thanks to Lauri Hornik for the opportunity to create this revised and updated second edition, to Carrie Crowe and Ella Hughes for their careful reading and feedback on the new chapter, to Herb Boyd, and to Ellen Cormier for her start-to-finish guidance throughout the new edition.

I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., August 28, 1963

I have the same dream for my children and grandchildren and for all young people who live in our land of the free. I dedicate this book to them.

I NTRODUCTION

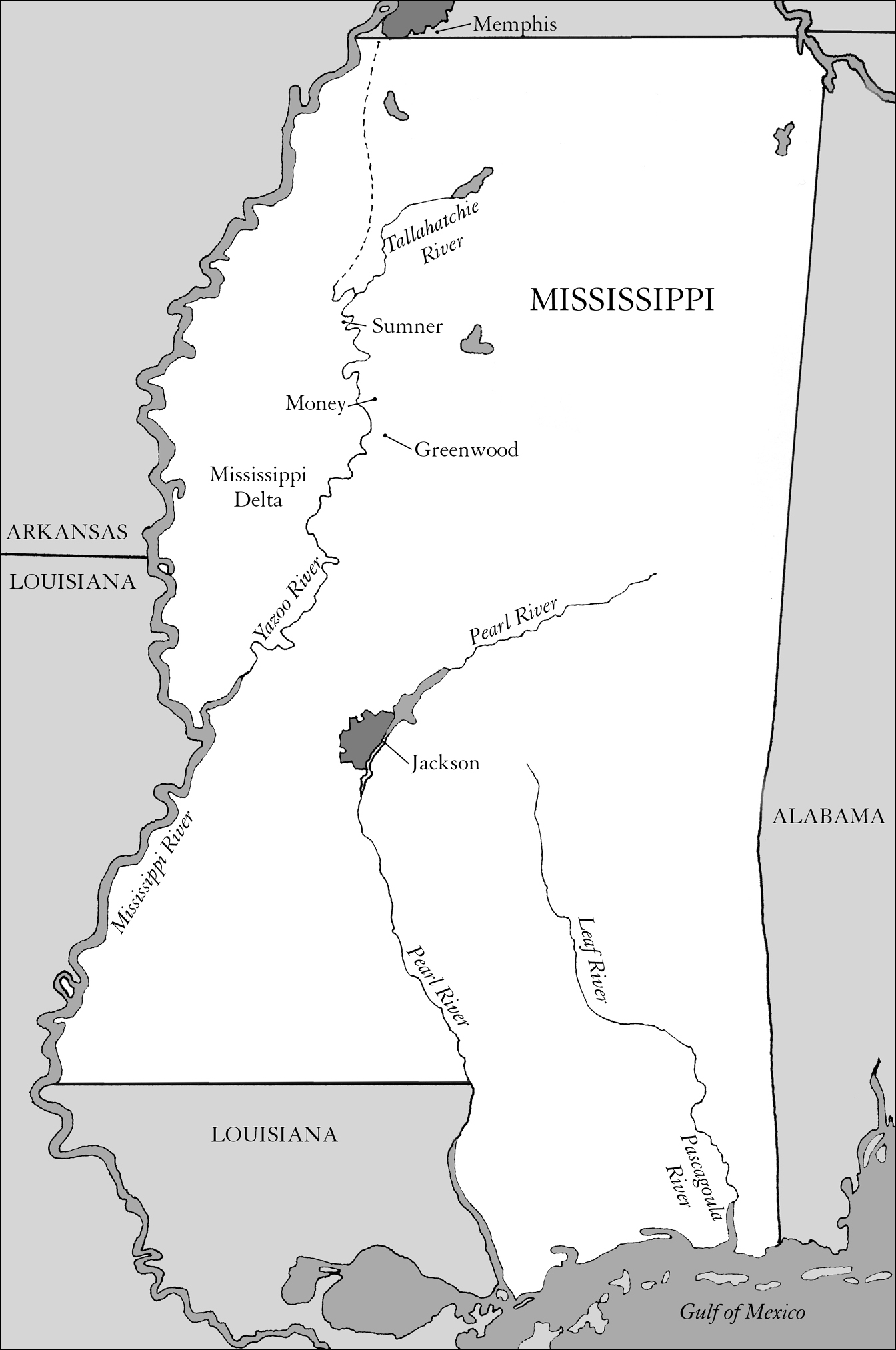

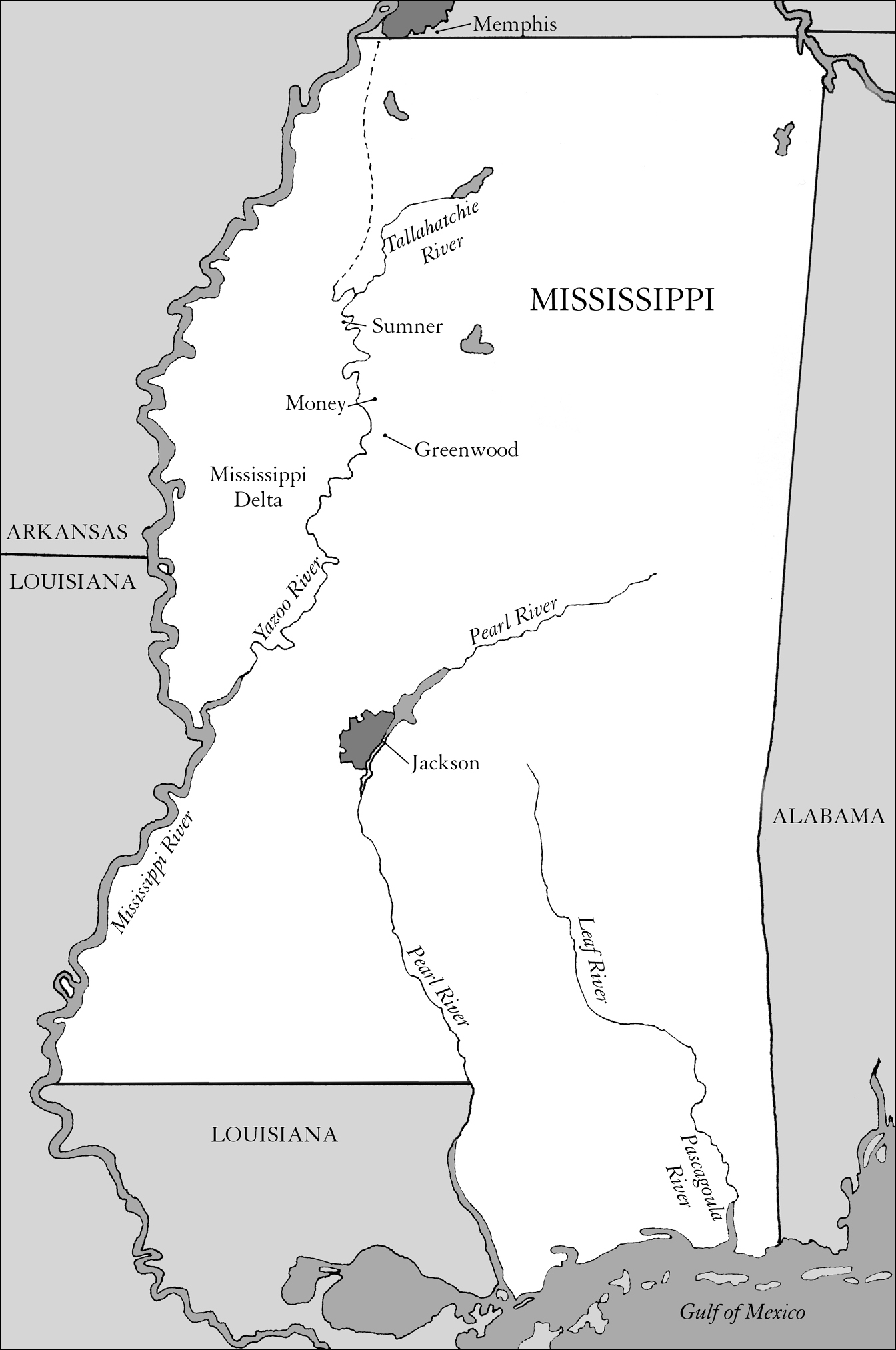

I was born near Chicago, Illinois, in 1954, just one year before fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was murdered in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi. Though his death and the trial of his murderers received national press coverage and especially intense attention in his hometown of Chicago, my parents recall nothing at all of the case or the news coverage of the trial.

But parents cant know everything, so school should have introduced me to this landmark civil rights event; but it didnt. Through elementary school, junior high, high school, college, and graduate school I never once read nor heard anything about Emmett Till. It wasnt until I was writing a book about the life and works of Newbery-winning author Mildred D. Taylor that I first encountered Emmett. In one of her essays, Taylor made a reference to a fourteen-year-old African American boy who had been murdered in her home state of Mississippi in 1955. I followed up on the reference to Emmett just to make sure it wasnt something I should include in my book about Taylor.

What I found stunned me: a gruesome photograph of this boy from Chicago, lying in a casket, his face and head horribly disfigured. The article that accompanied the photo grabbed my interest, not because it had anything to do with Mildred D. Taylor, but because it detailed a critical moment in American civil rights history that I, with all of my years of schooling and reading, had never learned. This article piqued my interest, and I dug some more, eventually finding two very helpful books about the case, Clenora Hudson-Weemss Emmett Till: The Sacrificial Lamb of the Civil Rights Movement and Stephen J. Whitfields A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till. Plater Robinson and his Soundprint radio documentary The Murder of Emmett Till also provided invaluable background information about the case.

So, who was Emmett Till and why hadnt I learned about him?

My initial research into the case showed that most white Americans had never heard of him, and a review of history textbooks suggested why. In a survey of twenty-one high school U.S. history books published between 1990 and 2002, I found that every book included information about two famous civil rights events: the U.S. Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education, and the Montgomery bus boycott started by Rosa Parks. Sadly, only two books mentioned Emmett Till, and those books used a combined total of fewer than fifty words to describe his place in American history. Neither book suggested that Emmetts murder had been a catalyst for the civil rights movement. A more recent survey of twenty-seven textbooks published between 2005 and 2016 showed that little has changed: three of the books devoted a sentence or two to the Till case, and one featured an entire page. The other twenty-three books made no mention of Emmett Till or of the significance of his murder.

But most African Americans know well his story and its place in history.

In addition to the thousands of people who attended Emmetts three-day viewing and the funeral that followed, hundreds of thousands more, including Mildred D. Taylor, read about his murder and the trial in the African American media of the time. The most sensational coverage of the murder, which included the photo of Emmetts battered body resting in his casket, appeared in