Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Elliott J. Gorn 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

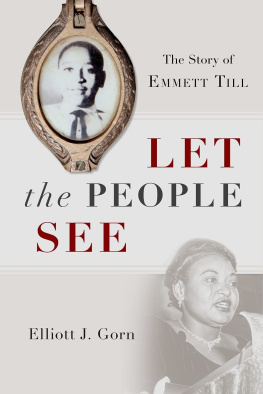

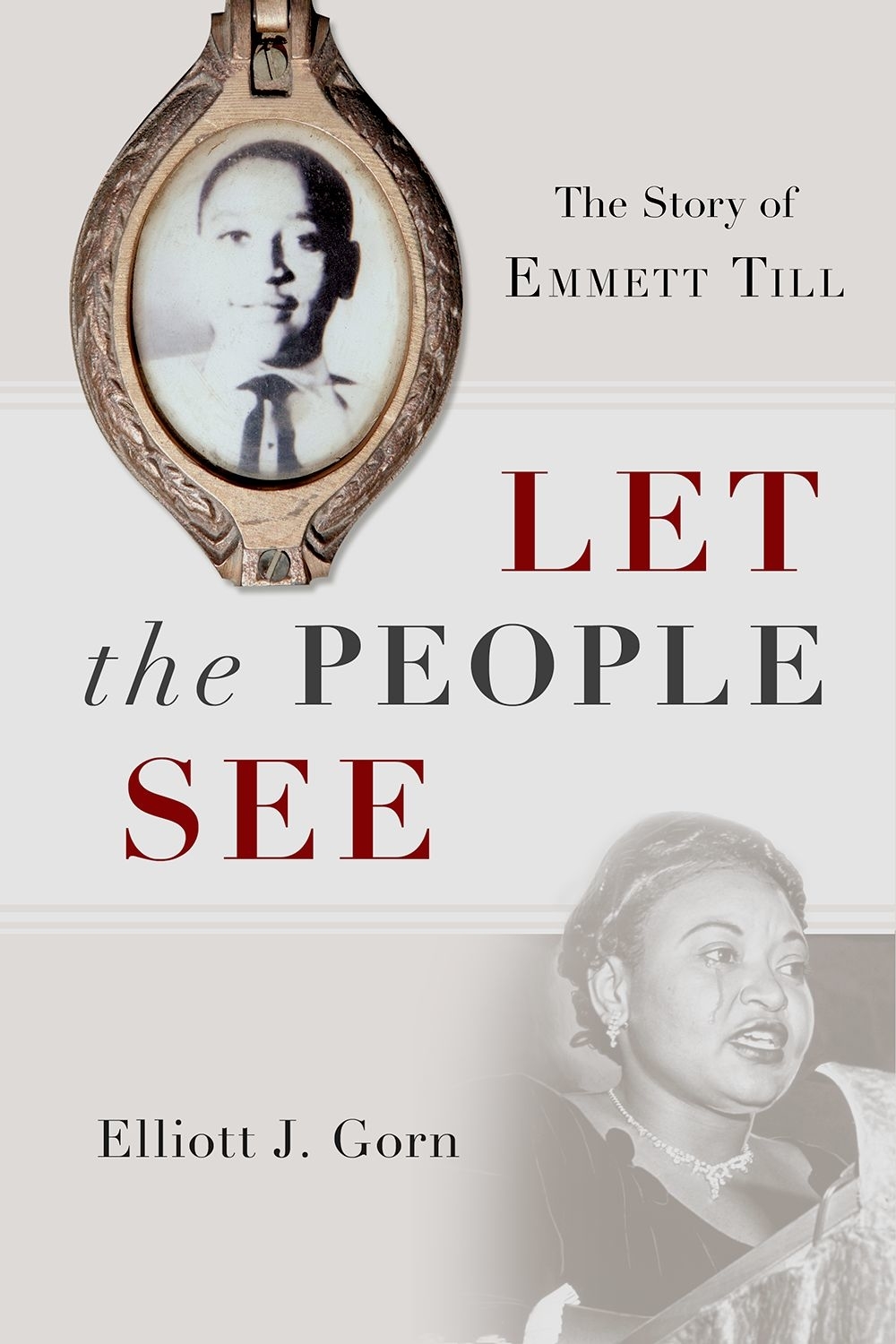

Title: Let the people see : the story of Emmett Till / Elliott J. Gorn.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018001885 | ISBN 9780199325122 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Till, Emmett, 19411955. |

LynchingMississippiHistory20th century. | African AmericansCrimes againstMississippi. | RacismMississippiHistory20th century | Trials (Murder)MississippiSumner. | Hate crimesMississippi. | Till-Mobley, Mamie, 19212003. | RacismMississippiHistory20th century. | United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. | MississippiRace relations.

Classification: LCC HV6465.M7 G67 2018 | DDC 364.1/34 [B] dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018001885

Contents

Chapter One

I Seen Two Knees and Feet

Chapter Two

Argo, Illinois

Chapter Three

Money, Mississippi

Chapter Four

Im Kinda Scared Theres Been Foul Play

Chapter Five

Lynching

Chapter Six

We Will Not Be Integrated

Chapter Seven

Let the People See What They Did to My Boy

Chapter Eight

Mississippis Infamy

Chapter Nine

A Good Place to Raise a Boy

Chapter Ten

The News Capitol of the United States

Chapter Eleven

Fair and Impartial Men

Chapter Twelve

Moses Wright

Chapter Thirteen

Undertaker Chester Miller

Chapter Fourteen

Sheriff George Smith and Deputy John Ed Cothran

Chaper Fifteen

Mamie Till Bradley

Chapter Sixteen

An Interracial Manhunt

Chapter Seventeen

Willie Reed

Chapter Eighteen

Carolyn Bryant

Chapter Nineteen

Sheriff Clarence Strider

Chapter Twenty

Doctor L. B. Otken and Undertaker H. D. Malone

Chapter Twenty-One

Your Forefathers Will Turn Over in Their Graves

Chapter Twenty-Two

Im Real Happy at the Result

Chapter Twenty-Three

The Soul of America

Chapter Twenty-Four

Each of You Own a Little Bit of Emmett

Chapter Twenty-Five

A Propaganda Victory for International Communism

Chapter Twenty-Six

Louis Till

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Evils Such as the Till Case are the Result of a System

Chapter Twenty-Eight

As Far as I Know, the Case is Closed

Chapter Twenty-Nine

We Call upon the President of the United States

Chapter Thirty

This Is a War in Mississippi

Chapter Thirty-One

Few Talk about the Till Case

Chapter Thirty-Two

The Time Had Come. I Could Feel It. I Could See It.

Chapter Thirty-Three

Weve Known His Story Forever

Chapter Thirty-Four

A Whistle or a Wink

Epilogue:

You Must Never Look Away from This

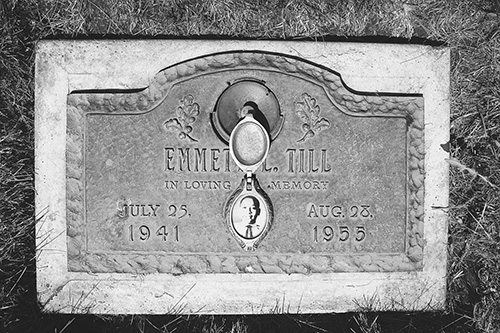

We all know the story: In late August 1955, a fourteen-year-old Chicago kid named Emmett Till went to visit family in Mississippi. At a crossroads store in the tiny Delta town of Money, Till whistled at the white woman behind the counter. A few days later, he was kidnapped, beaten, and shot. His abductors weighted his body down and threw it in the Tallahatchie River.

A friend of mine from Chicago was also fourteen when they murdered Emmett Till. He told me recently about the photo he saw back then in the newspaper, a photo of Tills body after it had been pulled from the river, his face crushed, a cotton-gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire as a weight.

No such photo exists. No journalists were by the riverbank to take pictures, and the police photographer who waited back at the sheriffs office in Greenwood took the official photos long after they cleaned the muck off Tills body and removed the weights tied around his neck.

Maybe my friend was thinking of the funeral pictures, taken a few days later in Chicago, and which have now become horrifically iconic. When Mamie Till Bradley saw how savagely her son had been beaten, she asked the mortician not to prettify him, and more, she insisted on a glass top over his coffin. Let the people see what they did to my boy, she famously said.

But I am sure my friend did not see those photos either. He is white. He was not a reader of Jet magazine or the Chicago Defender, two publications that carried them. African Americans across the country saw the pictures. They passed them around, discussed them, and took grim determination from them. While mainstream newspapers and magazines devoted lots of coverage to the Till story, none published the photos of Emmetts battered face. Few white Americans saw those now-infamous images until video documentaries of the Civil Rights Movement made by African Americans began to appear late in the 1980s.

Our memories are not always reliable. Emmett Tills story has been repeated so often in recent years, the photographs so widely reproduced, that it feels as if we have always known about them. Even as I write these words, a new cover story in Time magazine, The Most Influential Images of All Time, featuring the one hundred photos that changed the world, includes two of Emmett Till. These photographs proved a black life matters, Times editors declared; the pictures forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism.

Seeing had moral consequences in Times telling of the story; Americans were converted by the visceral impact of those horrifying images. But if seeing did not happen until decades later, then surely it could not explain that moral reckoning. Similarly, in 1995, forty years after covering the trial of Tills killers in Sumner, Mississippi, the journalist David Halberstam called it The first great media event of the Civil Rights Movement. Yet only after all that time had passed could Halberstam understand fully the significance of what he witnessed back in 1955, only then could he put the name Emmett Till together with media event and Civil Rights Movement.

The Till saga is like that. Our popular version of the story, worn smooth as an ancient ballad, tells the essential truths: that an innocent boy was murdered because he violated a social code he did not understand, that his mother invited the world to look at his destroyed face, and that her courage helped propel the Civil Rights Movement. All of this is true. The implied part, however, is not. That the crucifixion in Emmett Tills face softened white peoples hearts and put America on the road to racial justicethat, as a television report on CNN put it in 2003, everything changed after the murder of Emmett Tillis a pleasant untruth. Few white people saw the photographs. Radical change demanded years more struggle and far more blood.