A W REATH FOR E MMETT T ILL

M ARILYN N ELSON

I LLUSTRATED BY P HILIPPE L ARDY

Houghton Mifflin Company

Boston

F OR INNOCENCE MURDERED . F OR INNOCENCE ALIVE . M.N.

T O A RIANE . P.F.

T HE AUTHOR WOULD LIKE TO EXPRESS HER DEEP GRATITUDE

TO THE J. S. G UGGENHEIM M EMORIAL F OUNDATION FOR A FELLOWSHIP ,

AND TO THE U NIVERSITY OF D ELAWARE ,

WHICH FREED HER FROM A YEAR OF TEACHING SO THAT SHE COULD WRITE.

Text copyright 2005 by Marilyn Nelson

Illustrations copyright 2005 by Philippe Lardy

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com

The text of this book is set in Concord Nova.

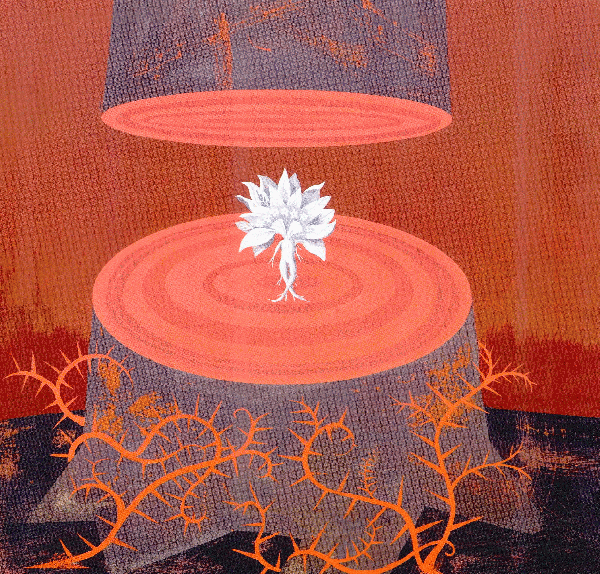

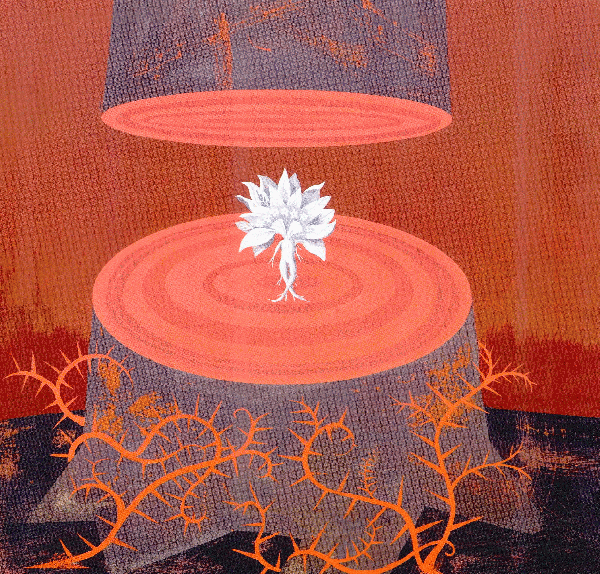

The illustrations are tempera on cardboard.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nelson, Marilyn, 1946

A wreath for Emmett Till / Marilyn Nelson ; illustrated by Philippe Lardy.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-618-39752-3

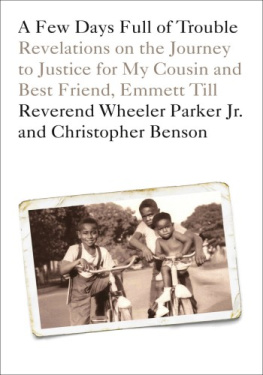

1. Till, Emmett, 19411955Juvenile poetry. 2. African AmericansCrimes againstJuvenile poetry. 3.

African American teenage boysJuvenile poetry. 4. Trials (Murder)Juvenile poetry. 5. Murder victimsJuvenile poetry.

6. Hate crimesJuvenile poetry. 7. MississippiJuvenile poetry. 8. LynchingJuvenile poetry.

9. Children's poetry, American. I. Lardy, Philippe. II. Title.

PS3573.A4795W73 2005

811'.54-dc22

2004009205

ISBN-13: 978-0618-39752-5

Printed in Singapore

TWP 10 9 8 7 6

How I Came to Write This Poem

I was nine years old when Emmett Till was lynched in 1955. His name and history have been a part of most of my life. When I decided to write a poem about lynching for young people, I knew that I would write about Emmett Till. He was lynched when he was the age of the young people who might read my poem. After revisiting what I knew about lynching, reading more about it, and growing increasingly depressed, I also knew that I would write this poem as a heroic crown of sonnets.

A sonnet is a fourteen-line rhyming poem in iambic pentameter. The rhyme scheme I chose to use in these sonnets is called Italian, or Petrarchan (after Petrarch, 13041374, the poet who invented it). A crown of sonnets is a sequence of interlinked sonnets in which the last line of one becomes the first line, sometimes slightly altered, of the next. A heroic crown of sonnets is a sequence of fifteen interlinked sonnets, in which the last one is made up of the first lines of the preceding fourteen.

When I decided to use this form, I had seen only one heroic crown of sonnets, a fantastically beautiful poem by the Danish poet Inger Christensen. Instead of thinking too much about the painful subject of lynching, I thought about what Inger Christensen's strategy must have been. The strict form became a kind of insulation, a way of protecting myself from the intense pain of the subject matter, and a way to allow the Muse to determine what the poem would say. I wrote this poem with my heart in my mouth and tears in my eyes, breathless with anticipation and surprise.

A W REATH FOR

E MMETT T ILL

R.I.P E MMETT L OUIS T ILL 19411955

Rosemary for remembrance, Shakespeare wrote:

a speech for poor Ophelia, who went mad

when her love killed her father. Flowers had

a language then. Rose petals in a note

said, I love you; a sheaf of bearded oat

said, Your music enchants me. Goldenrod:

Be careful. Weeping-willow twigs: I'm sad.

What should my wreath for Emmett Till denote?

First, heliotrope, for Justice shall be done.

Daisies and white lilacs, for Innocence.

Then mandrake: Honor (wearing a white hood,

or bare-faced, laughing). For grief, more than one,

for one is not enough: rue, yew, cypress.

Forget-me-nots. Though if I could, I would

Forget him not. Though if I could, I would

forget much of that racial memory.

No: I remember, like a haunted tree

set off from other trees in the wildwood

by one bare bough. If trees could speak, it could

describe, in words beyond words, make us see

the strange fruit that still ghosts its reverie,

misty companion of its solitude.

Dendrochronology could give its age

in centuries, by counting annual rings:

seasons of drought and rain. But one night, blood,

spilled at its roots, blighted its foliage.

Pith outward, it has been slowly dying,

pierced by the screams of a shortened childhood.

Pierced by the screams of a shortened childhood,

my heartwood has been scarred for fifty years

by what I heard, with hundreds of green ears.

That jackal laughter. Two hundred years I stood

listening to small struggles to find food,

to the songs of creature life, which disappears

and comes again, to the music of the spheres.

Two hundred years of deaths I understood.

Then slaughter axed one quiet summer night,

shivering the deep silence of the stars.

A running boy, five men in close pursuit.

One dark, five pale faces in the moonlight.

Noise, silence, back-slaps. One match, five cigars.

Emmett Till's name still catches in the throat.

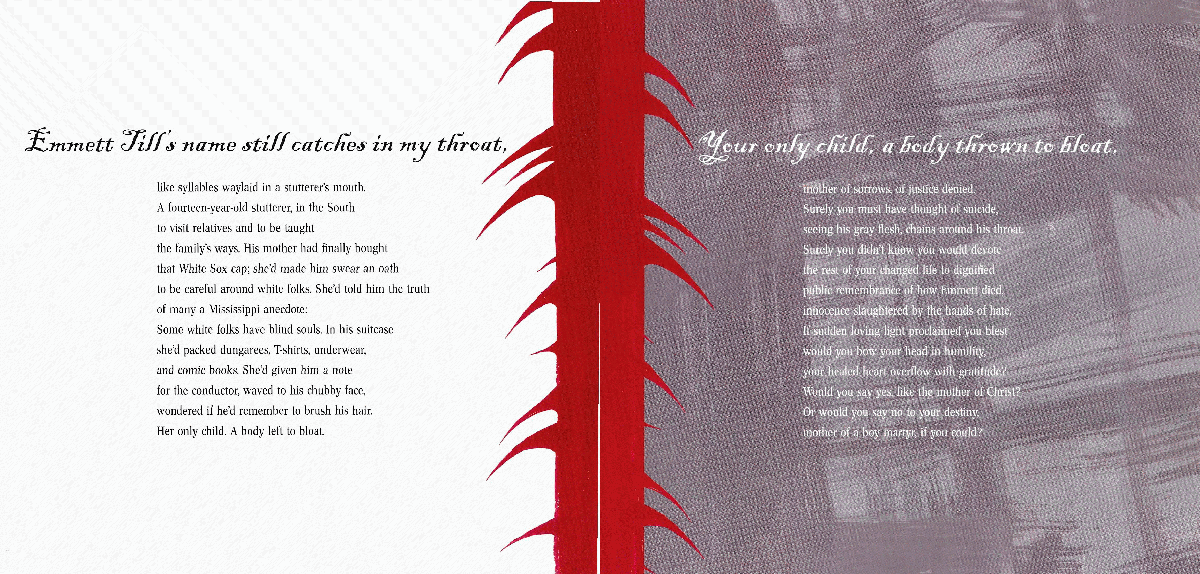

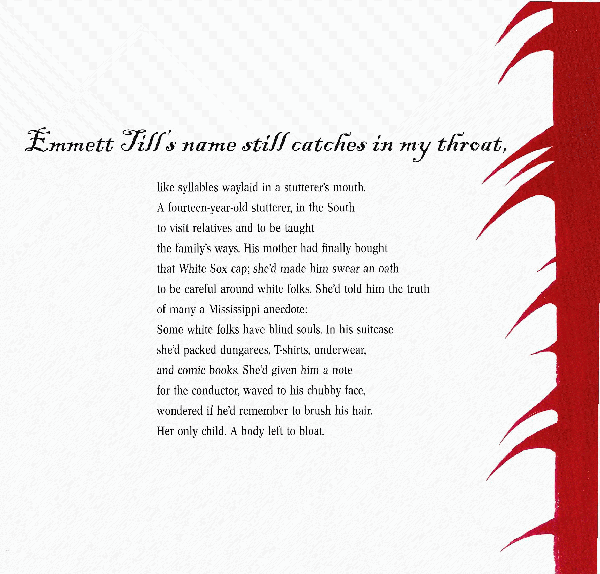

Emmett Till's name still catches in my throat,

like syllables waylaid in a stutterer's mouth.

A fourteen-year-old stutterer, in the South

to visit relatives and to be taught

the family's ways. His mother had finally bought

that White Sox cap; she'd made him swear an oath

to be careful around white folks. She'd told him the truth

of many a Mississippi anecdote:

Some white folks have blind souls. In his suitcase

she'd packed dungarees, T-shirts, underwear,

and comic books. She'd given him a note

for the conductor, waved to his chubby face,

wondered if he'd remember to brush his hair.

Her only child. A body left to bloat.

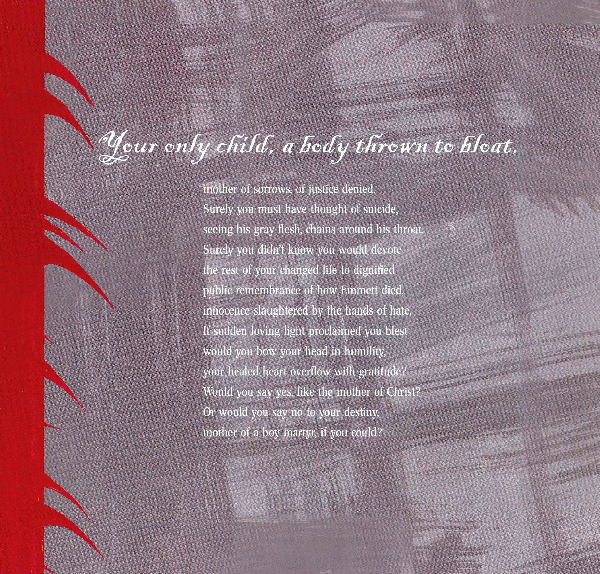

Your only child, a body thrown to bloat,

mother of sorrows, of justice denied.

Next page