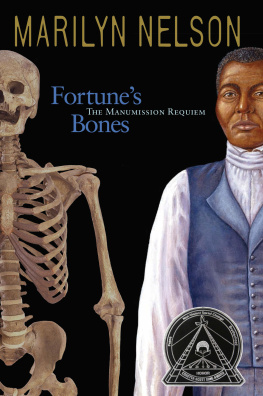

WE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONNECTICUT COMMISSION ON THE ARTS AND THE MATTATUCK MUSEUM OF WATERBURY, CONNECTICUT, WHOSE GENEROSITY AND COOPERATION MADE THE PROJECT POSSIBLE. Poem copyright 2016, 2003 by Marilyn NelsonNotes copyright 2016, 2004 by Pamela EspelandImages copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumAfterword copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumMusic copyright 2016, 2004 by Ysaye M. BarnwellAll rights reservedPrinted in ChinaDesigned by Helen RobinsonFourth printingLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nelson, Marilyn Fortunes bones : the manumission requiem / Marilyn Nelson.1st ed. p. cm. ). ).

WE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONNECTICUT COMMISSION ON THE ARTS AND THE MATTATUCK MUSEUM OF WATERBURY, CONNECTICUT, WHOSE GENEROSITY AND COOPERATION MADE THE PROJECT POSSIBLE. Poem copyright 2016, 2003 by Marilyn NelsonNotes copyright 2016, 2004 by Pamela EspelandImages copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumAfterword copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumMusic copyright 2016, 2004 by Ysaye M. BarnwellAll rights reservedPrinted in ChinaDesigned by Helen RobinsonFourth printingLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nelson, Marilyn Fortunes bones : the manumission requiem / Marilyn Nelson.1st ed. p. cm. ). ).

ISBN 978-1932425123 (hc) ISBN 1-932425-12-8 (alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-62979-588-1 (e-book) 1. SlavesPoetry. 2. SlaveryPoetry. 3.

ConnecticutPoetry. 4. African AmericansPoetry. 5. Young adult poetry, American. Title. Title.

PS 3573.A4795F64 2004 811.54-dc22 2004046917 H4.1  Contents spokencontraltobaritone I and choirchoir with solosbaritone II with choirchoir

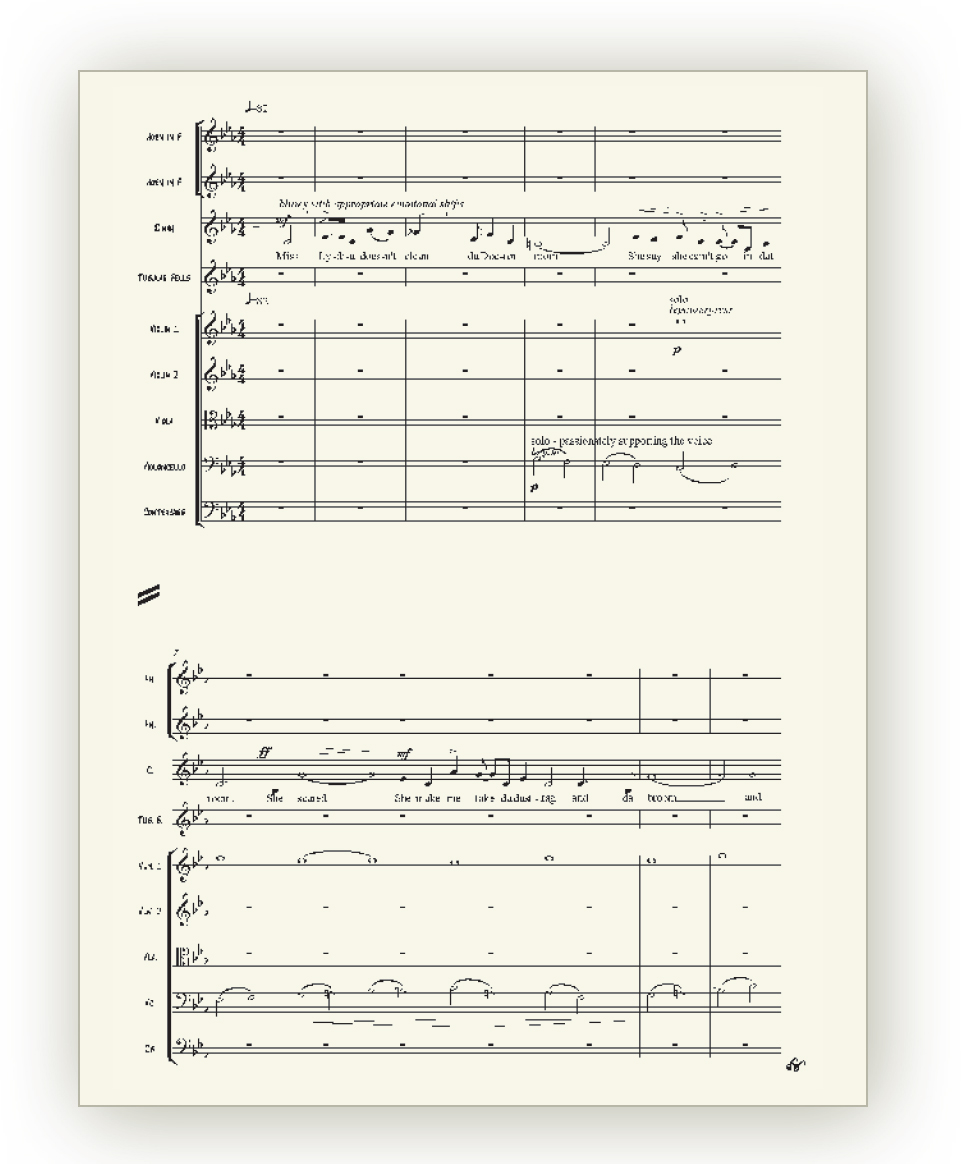

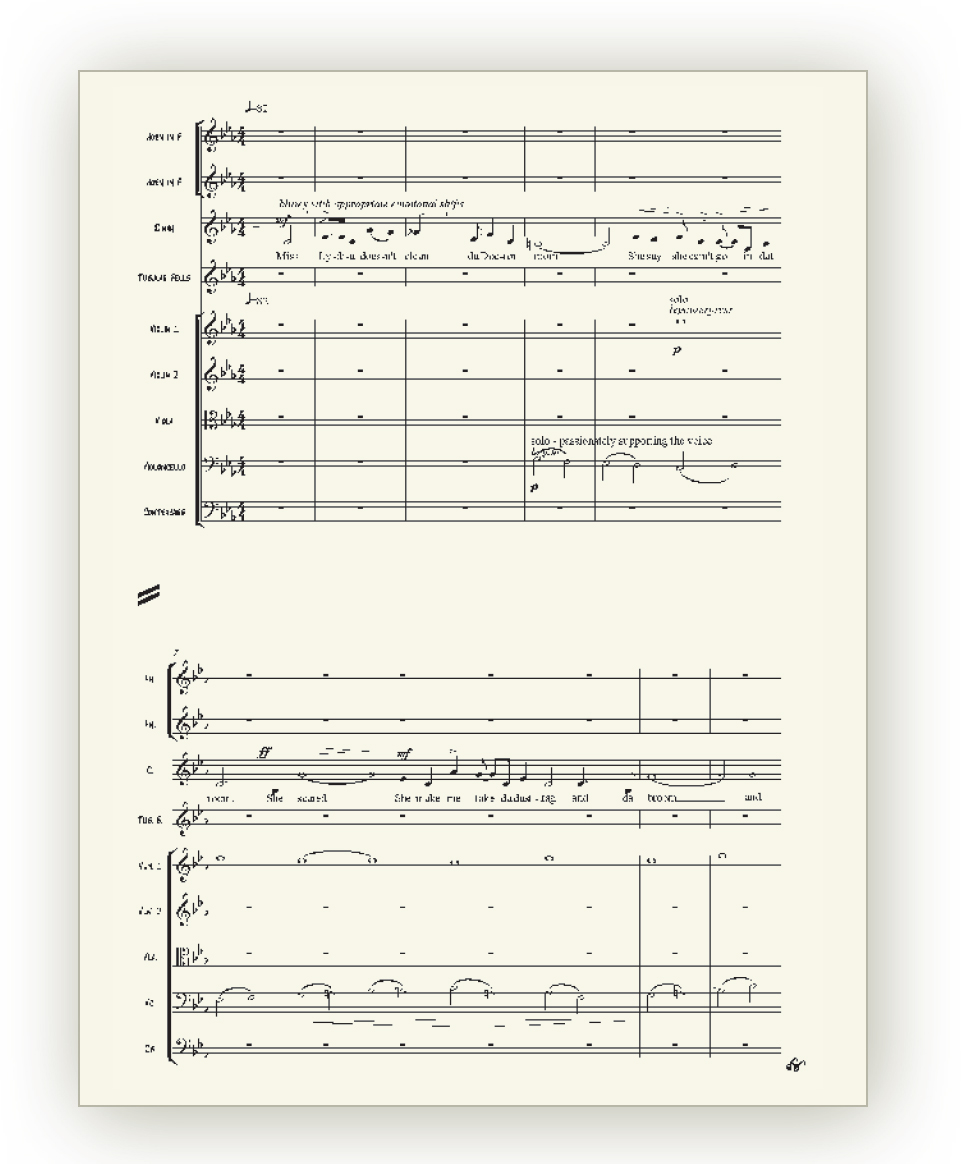

Contents spokencontraltobaritone I and choirchoir with solosbaritone II with choirchoir Preliminary score for The Manumission Requiem by Dr. Ysaye M. BarnwellManumission: The formal release of someone who has been a slave. From the Latin words manus (hand) and mittere (to release, let go, or send). Literally to release the hand of authority. Slave owners could choose to free their slaves.

Preliminary score for The Manumission Requiem by Dr. Ysaye M. BarnwellManumission: The formal release of someone who has been a slave. From the Latin words manus (hand) and mittere (to release, let go, or send). Literally to release the hand of authority. Slave owners could choose to free their slaves.

Sometimes slaves were freed if they converted to their masters religion. Requiem: Words and music written to honor the dead. The first word of the Introit (first part) of the Mass for the Dead (missa pro defunctis): Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine: et lux perpetua luceat eis (Give them eternal rest, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them ) A musical setting of the requiem mass; a musical composition in honor of someone who has died. Famous requiems have been written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Hector Berlioz, Gabriel Faur, and Benjamin Britten, to name a few. Music for The Manumission Requiem has been composed by Dr. Barnwell. The Manumission Requiem: Written to honor a slave named Fortune, freed from slavery by death. The Manumission Requiem: Written to honor a slave named Fortune, freed from slavery by death.

Although Fortune was baptized in St. Johns Episcopal Church in Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1797, conversion did not make slaves free in that state after 1729. Fortune was never freed during his lifetime. He was one of the last slaves in Waterbury. In 1730, some 27 people were enslaved there. By 1790, that number had dropped to 12.

Five were members of Fortunes family, all owned by Dr. Preserved Porter. Authors Note I wrote The Manumission Requiem soon after the events of September 11, 2001. I was hearing classical composers requiems for the dead on public radio, and also clicking every day, as I always do, on the Hunger Site ( www.hungersite.com ) to donate food for the worlds hungry. Every day I read on that website that about 24,000 people die each day from hunger or hunger-related causes. I decided to dedicate my requiem to everyone in the world who died on 9/11the victims of the terrorist attacks, but also the victims of starvation, of illness, of poverty, of war, of old age, of neglect: Everyone.

My requiem has some but not all of the elements of a traditional funeral mass: the Introit (I call it a Preface), the Kyrie (the prayer of Kyrie eleison, Greek for Lord, have mercy), and the Sanctus, a hymn of praise. What is for me the high point of my requiem is Not My Bones, which I imagined Fortune singing in his own voice. This is not part of the traditional funeral mass. When Fortune says, You are not your body, he is quoting an ancient teaching. I learned it from Thich Nhat Hanh, the great Vietnamese Buddhist world leader, spiritual guide, and writer. After hearing him lecture, someone asked him, What is the most helpful thing you can say to a person who is dying? Thich Nhat Hanh replied, We have learned, from our visits to hospices, that the most helpful thing we can say is, Dont worry.

The body that is dying here is not you. These words allow people to accept their deaths with peace. A requiem, by definition, is sad; the person it honors has died. But manumissionthe freeing of a slaveis a joyous event. By calling this The Manumission Requiem, Im setting grief side by side with joy. Im trying to imitate a traditional New Orleans brass band jazz funeral.

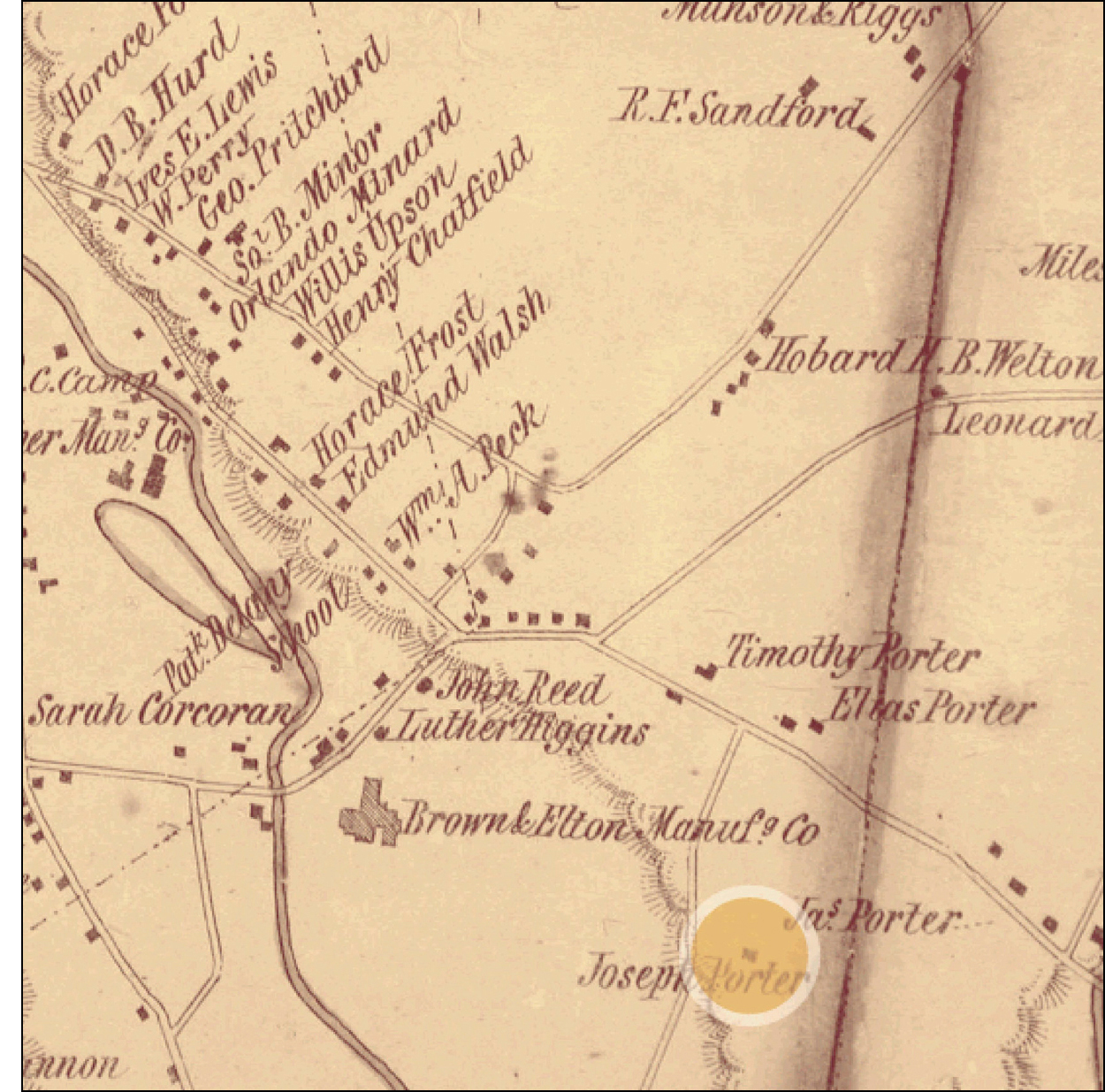

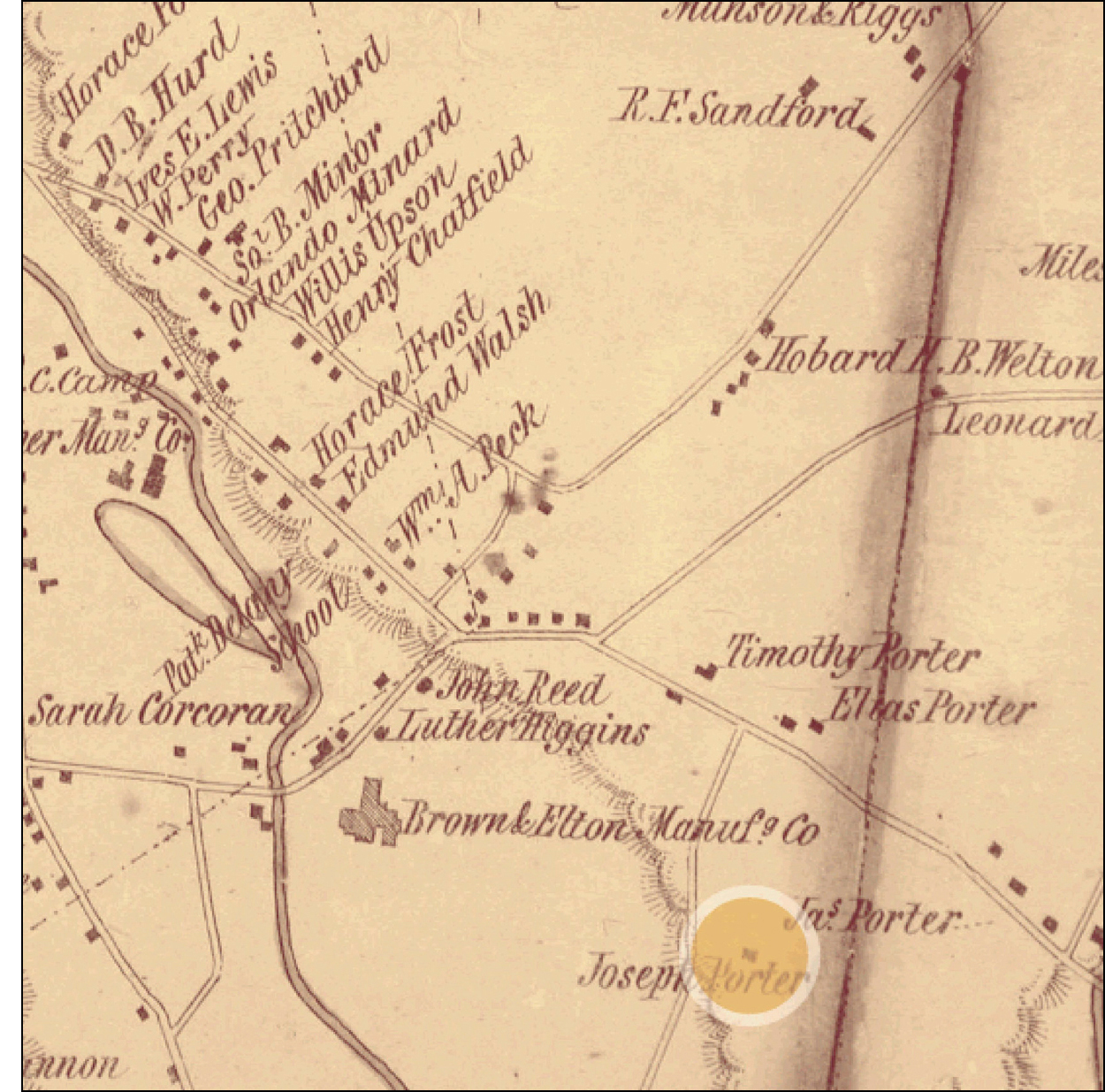

When the mourners follow the body to the cemetery, they are solemn and sorrowful, and so is the music. But after the burial, after they leave the cemetery, the music becomes jubilant. The mourners dance joyfully through the streets in what they call a second-line parade. And crowds of people, passers-by, strangers, come out and join them. What was a dirge for the dead becomes a celebration of life. Marilyn Nelson THE MANUMISSION REQUIEM Map of Waterbury, Connecticut, from 1852, showing the location of the Porter farm. Before Fortune was bones in a Connecticut museum, he was a husband, a father, a baptized Christian, and a slave.

Map of Waterbury, Connecticut, from 1852, showing the location of the Porter farm. Before Fortune was bones in a Connecticut museum, he was a husband, a father, a baptized Christian, and a slave.

His wifes name was Dinah. His sons were Africa and Jacob. His daughters were Mira and Roxa. He was baptized in an Episcopal church, which did not make him free. His master was Dr. Preserved Porter, a physician who specialized in setting broken bones.

They lived in Waterbury, Connecticut, in the late 1700s. Dr. Porter had a 75-acre farm, which Fortune probably ran. He planted and harvested corn, rye, potatoes, onions, apples, buckwheat, oats, and hay. He cared for the cattle and hogs. Unlike many slaves, who owned little or nothing and were often separated from their families, Fortune owned a small house near Dr.

Porters home. He and Dinah and their children lived together. Preface Fortune was born; he died. Between those truths stretched years of drudgery, years of pit-deep sleep in which he hauled and lifted, dug and plowed, glimpsing the steep impossibility of freedom. Fortunes bones say he was strong; they speak of cleared acres, miles of stone walls. They say work broke his back: Before it healed, they say, he suffered years of wrenching pain.

His wife was worth ten dollars. And their son a hundred sixty-six. A man unmanned, he must sometimes have waked with balled-up fists. A white priest painted water on his head and Fortune may or may not have believed, whom Christ offered no respite, no reprieve, only salvation. Fortunes legacy was his inheritance: the hopeless hope of a people valued for their labor, not for their ability to watch and dream as vees of geese define fall evening skies.  Eighteenth-century silk embroidery by Prudence Punderson entitled The First, Second and Last Scene of Mortality (The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut)

Eighteenth-century silk embroidery by Prudence Punderson entitled The First, Second and Last Scene of Mortality (The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut)

Next page

WE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONNECTICUT COMMISSION ON THE ARTS AND THE MATTATUCK MUSEUM OF WATERBURY, CONNECTICUT, WHOSE GENEROSITY AND COOPERATION MADE THE PROJECT POSSIBLE. Poem copyright 2016, 2003 by Marilyn NelsonNotes copyright 2016, 2004 by Pamela EspelandImages copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumAfterword copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumMusic copyright 2016, 2004 by Ysaye M. BarnwellAll rights reservedPrinted in ChinaDesigned by Helen RobinsonFourth printingLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nelson, Marilyn Fortunes bones : the manumission requiem / Marilyn Nelson.1st ed. p. cm. ). ).

WE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONNECTICUT COMMISSION ON THE ARTS AND THE MATTATUCK MUSEUM OF WATERBURY, CONNECTICUT, WHOSE GENEROSITY AND COOPERATION MADE THE PROJECT POSSIBLE. Poem copyright 2016, 2003 by Marilyn NelsonNotes copyright 2016, 2004 by Pamela EspelandImages copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumAfterword copyright 2016, 2004 by the Mattatuck MuseumMusic copyright 2016, 2004 by Ysaye M. BarnwellAll rights reservedPrinted in ChinaDesigned by Helen RobinsonFourth printingLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nelson, Marilyn Fortunes bones : the manumission requiem / Marilyn Nelson.1st ed. p. cm. ). ). Contents spokencontraltobaritone I and choirchoir with solosbaritone II with choirchoir

Contents spokencontraltobaritone I and choirchoir with solosbaritone II with choirchoir Preliminary score for The Manumission Requiem by Dr. Ysaye M. BarnwellManumission: The formal release of someone who has been a slave. From the Latin words manus (hand) and mittere (to release, let go, or send). Literally to release the hand of authority. Slave owners could choose to free their slaves.

Preliminary score for The Manumission Requiem by Dr. Ysaye M. BarnwellManumission: The formal release of someone who has been a slave. From the Latin words manus (hand) and mittere (to release, let go, or send). Literally to release the hand of authority. Slave owners could choose to free their slaves. Map of Waterbury, Connecticut, from 1852, showing the location of the Porter farm. Before Fortune was bones in a Connecticut museum, he was a husband, a father, a baptized Christian, and a slave.

Map of Waterbury, Connecticut, from 1852, showing the location of the Porter farm. Before Fortune was bones in a Connecticut museum, he was a husband, a father, a baptized Christian, and a slave. Eighteenth-century silk embroidery by Prudence Punderson entitled The First, Second and Last Scene of Mortality (The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut)

Eighteenth-century silk embroidery by Prudence Punderson entitled The First, Second and Last Scene of Mortality (The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut)