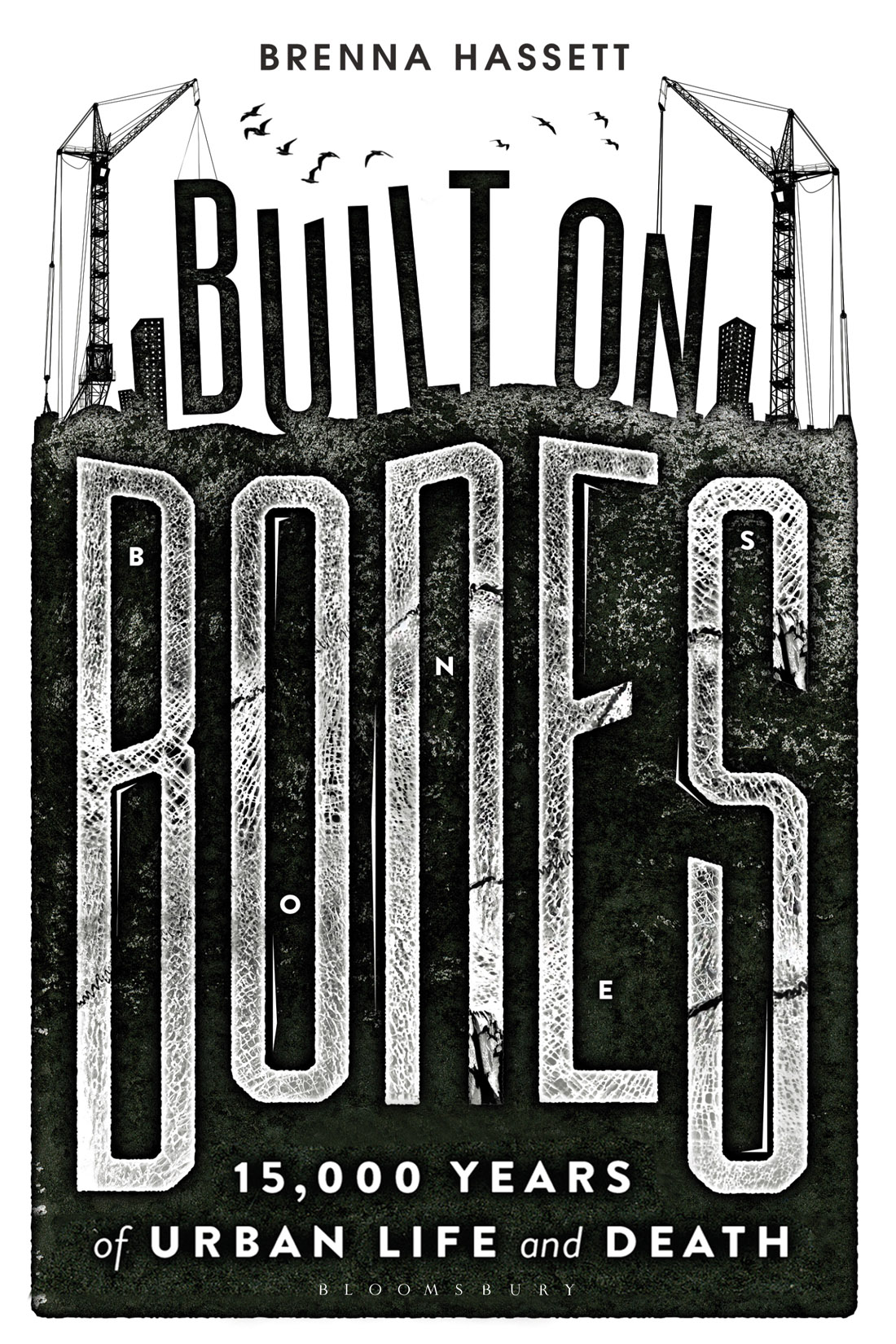

Brenna Hassett - Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death

Here you can read online Brenna Hassett - Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

p53: The Gene that Cracked the Cancer Code by Sue Armstrong

Atoms Under the Floorboards by Chris Woodford

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

Chilled by Tom Jackson

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Breaking the Chains of Gravity by Amy Shira Teitel

Suspicious Minds by Rob Brotherton

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Electronic Dreams by Tom Lean

Sorting the Beef from the Bull by Richard Evershed and Nicola Temple

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Furry Logic by Matin Durrani and Liz Kalaugher

This book is dedicated to all those perfect leaves of grass, who have already gone to the dirt to grow.

Contents

The amount of time humans have spent living in cities is an infinitesimal speck in the scope of hominid evolution. It took our species something like 200,000 years to get around to trying out living in the same place all year round. Then, it took thousands of years of experimentation for those patchy early settlements to become the cities we recognise today, and its just in these last few years that the number of city dwellers has finally outstripped that of our country cousins. We are now officially an urban planet but why did it take us so long to get here? If cities are so great, why are they full of things that kill us? Urban life serves up a terrifying cocktail of the most dangerous things known to our species disease, inequality and, of course, other people. Its not unreasonable to ask: why have we made cities this way?

However, there is a better question, and its one that you can only ask with a bit of patience and a whole lot of dead people on your hands. If we look at the lives and deaths of people through all the different experimental stages of urban life, we can start to see some very interesting patterns in these urban pioneers. Patterns of disease. Patterns of malnutrition. Shrinking faces and growing numbers. Broken backs, broken skulls, bone missing where you want it and piling up where you dont the speechless generations of the past still have quite a story to tell. Its through the skeletal remains of the city dwellers of the past that we can answer the question this book asks, and it matters to everyone alive today: why have cities made us this way?

Its fairly simple to look out of a twenty-first-century window at a sky full of hazy smog, over the glare of fossil-fuel-powered lights and particulate-belching vehicles, and come to the conclusion that cities are a hazard to human wandering? Werent we happier then?

Look at them. Just there. Coming over the ridge, at first silhouetted starkly against the rising sun but with the details of their bodies edging into visibility as they break the top of the dune and begin their descent. He (and we must always talk about him first because androcentrism is a palaeo tradition) is a paragon of human virtue. He is whippet-lean, with tight bulging calves and washboard abs. His hair, depending on your personal taste, might be in a man-bun, with sun-kissed flyaway strands held back by some sort of musk ox leather hairband; or maybe hes got neat dreads that really frame his face. She, on the other hand, is more difficult to describe, largely because shes got children strapped to most of her body, covering the bits that the weirdly tiny and ragged scrapes of animal hide shes wearing dont, and is carrying yet another infant in her admittedly well-muscled arms. He, by contrast, gets a spear and one of those shell necklaces surfer guys wear. This, ladies and gentlemen, is the wave of the future past. Lean, low-fat bodies, natural-fibre clothing and full-attachment parenting. Our model couple, meandering across the dunes of my advertising-and-Raquel-Welch-blighted imagination, are the absolute apogee of what our modern neuroses tell us life was like when we lived naturally. Those washboard abs (his and hers, which you can see if she detaches the middle-sized child temporarily) are the product of eating a palaeo-diet, those enviable leg muscles the product of barefoot exercise, and the brood of happy children the product of (and yes, I swear to you now, this is an actual thing) palaeo-parenting.

What a lovely image. How far removed from the depressing sight of yet another overweight family group fighting in their car outside a drive-through fast food restaurant. The proponents of the palaeo-diet tell us that, if those harassed and harried parents in the leased minivan just gave up the burger bun and went for the animal style option, his incipient diabetes and her chronic gut issues would simply disappear, and theyd both be left with nothing but toned muscles, glowing skin and glossy hair. Palaeo-lifestyle advocates, like those who reject shoes or letting your toddler take his attention issues out on an iPad rather than your frayed last nerve, have similar advice. It comes from a thousand corners of the internet, magazines, TV and talk shows the not-so-subtle message that weve all become a little too modern for our own good. Too settled, too sedentary, too dependent on our easy carbs and cushioned walkwear.

But are they right ? If we can look around at how we live now and see that, in many ways, its killing us well then, why are we doing it? Why do we live in our big cities, with our Big Gulps and our bigger bellies? Theres a quick answer and a longer one. This book, I hope, is the longer one, but we can get a short answer just by zooming in on our palaeo-couple as they trudge across the savanna. What do we really know about them? We can imagine what we like, but how can we get real information on what it was like to live as a hunter-gatherer? Its actually not that hard. Archaeology, as most people will know, is the science of recreating the human past. Bio archaeology, which most people ought to be forgiven for never having heard of, is the science of reconstructing lives in that human past. Bioarchaeology takes the remains of living things, such as skeletons and teeth (but even potentially hair, skin and even nails), and from the wealth of information locked inside the structure, composition, shape and size of these ancient clues, tells us how people (and animals) lived and died in the past. Human remains can tell us about life in the past to an unbelievable level of detail. For instance, lets look back at our palaeo-parents.

Take a closer look at Spear Guy. How tall is he? Actually, fairly tall around 1.79 metres, or about 5 foot 9 inches. When archaeologists find his bones in 15,000 years time, they will take careful measurements of all of his limb bones the femur, the humerus, the tibia and will plug these measurements into a formula that will estimate his height. Those musclebound limbs weve been seedily admiring will also show up, but this time with the help of a machine. By CT-scanning his bones, bioarchaeologists can reconstruct his bone density, giving us a clue as to whether he was more couch potato or rolling stone. On the outside of his bones, more clues about activity abound. Take a look at his arms, especially the one he holds the spear in. Where his most pronounced musculature is in life, so will it be in death the places on his arms where those spear-thrusting or throwing muscles attach will be more marked than on his gender-stereotyped partner, who presumably isnt stabbing or throwing the kids shes carrying in quite the same way as she would a spear.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

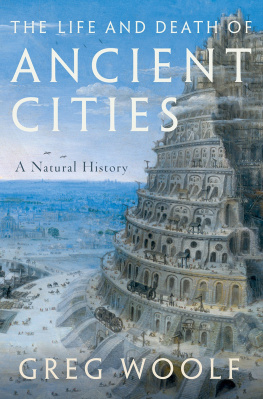

Similar books «Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death»

Look at similar books to Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Built on Bones: 15,000 Years of Urban Life and Death and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.