1. Prologue

Einsteins annus mirabilis of 1905 saw the publication of his investigations into the theory of Brownian motion, his theory of special relativity, and, most revolutionary of all, his paper on light quanta, in which he extended Plancks quantization of material oscillators to electromagnetic radiation, thereby affording an immediate understanding ofamongst other thingsthe photoelectric effect , for which, 16 years later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. Some 25 years later in 1930, at the University of Munich, the photoelectric effect was the subject of the doctoral dissertation of the theoretical physicist HERBERT FRHLICH , 190591 (Fig. ).

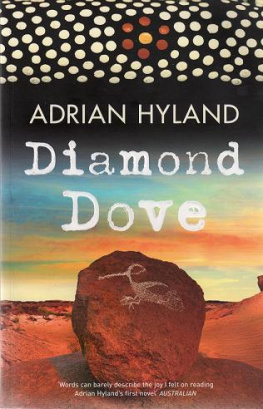

Fig. 1.1

Herbert Frhlich, 19051991

Frhlichs illustrious career, which started just after the new quantum mechanics had been formulated, and which went on to span some 60 years during which many developments in physics took place, was distinguished by the diversity of the fields in which he was active and to which he contributed so significantly. His contributions often influenced subsequent developments, sometimes in a fundamental way, and often revealed some hitherto unsuspected connection between seemingly quite unrelated areas of physics, and later, even between physics and biology. The hallmark of his particular genius was an ability to recognize when new ideas genuinely had to be introduced and when they did not. It was not only from this ability to balance the radical with the conservative that his most significant contributions arose, but also from his consummate skill in identifying the particular aspect of a given phenomenon on which to focus attention, thereby often unearthing some hitherto unsuspected possibility within a pre-existing theoretical framework, thus removing the need for ad hoc hypotheses. The decisive influence he exertedoften as a man ahead of his timein fields as diverse as meson theory and biology stands as a strong indictment against fragmentation and over-specialization in theoretical physics, something that was quite alien to his holistic perception of the subject. Indeed, so much ahead of his time was he that he pioneered a number of topics long before some of them were rediscovered later by others who now take much of the credit; these include: the prediction of (i) a neutral meson and a quartet of vector mesons, (ii) a partial anticipation of the Lyddane-Sachs-Teller relation, (iii) an interaction between the nuclear spins in a metal mediated by conduction electrons, (iv) hot electron physics, (v) ferroelectric soft modes, (vi) polaritons, (vii) a phonon-mediated electron-electron attraction as the basis of superconductivity, (viii) sliding modes in low-dimensional conducting systems, (ix) the importance of size effects in finite samples, both in solid-state physics and biology.

Most influential of all, however, was undoubtedly his introduction, in the early 1950s, of the methods of quantum field theory into solid-state physics, which completely revolutionised the future development of the subject, and of statistical mechanics in general.

43 years of Frhlichs working life were spent at the University of Liverpool in the UK , where he occupied, with great distinction, the first Chair of Theoretical Physics from 1948 until his retirement in 1973. This occasion was marked by a Festschrift , Cooperative Phenomena, edited by H. Haken and M. Wagner, and published by Springer Verlag. A post-retirement position at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies had been seriously considered, but did not materialise, and he was appointed Professor Emeritus in Liverpool, a position he held until his death on 23 January 1991 at the age of 85. Between 1973 and 1976, he was Professor of Solid-State Electronics at the University of Salford, UK , and his 80th birthday saw the publication by Springer of a second Festschrift , Electron Transfer Dynamics, edited by T.W. Barrett and H.A. Pohl.

Before moving to Liverpool, Frhlich was Reader in Physics at the University of Bristol to where he had come from Russia in 1935 as a refugee from Stalins purges, having left his native Germany after being dismissed by the Nazis from his university post in Freiburg in 1933, shortly after his appointment as Privatdozent had been ratified. Prior to this, he had been a doctoral student of Sommerfeld in Munich, receiving his D.Phil. in 1930, after only two years of study. Internationally, he was a highly respected figure whose status as a colossus in the world of Theoretical Physics was undisputed. His circle of friends and colleagues included such illuminati as Sommerfeld (his doctoral supervisor), Heisenberg,Schrdinger, Bohr,Feynman and Pauli, who, of Frhlich, once declared, Ah yes, there we have someone who can not only calculate, but can also think! [J. Mehrapersonal communication, c .1990].

Frhlich became a Fellow of the Physical Society of Great Britain in 1944, was elected and received numerous Honorary Degrees worldwide (see Chronology ).

On several occasions between 1954 and 1972, he was invited to submit nominations to the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences Nobel Committee for Physics, and between 1973 and (at least) 1988 he annually proposed a candidate for the Max Planck Medal.

During the late 1960s, at the invitation of Hermann Haken (who had been a young Visiting Research Fellow in Liverpool during the late 1950s), he started to make regular visits to Stuttgart where he gave many stimulating lectures at the Theoretical Physics Institute of which Haken was, by then, Director. The connection with Stuttgart intensified after 1970 with the opening of the Max Planck Institute for Solid-state Physics to where he was invited by its first Director, Ludwig Genzel, and where, from 1979 to 1991, Frhlich was a Foreign Member, regularly making extended visits. Peter Fuldea former director of one of the Institutes research groups, who remembers these many visitsis quite sure that Frhlichs relationship with Germany was not at all embittered by his pre-war experiences, some of which he dismissed as reminiscent of a fairly amusing adventure film.

Frhlich travelled extensively, visiting many parts of the world, lecturing, and exchanging ideas with other physicists, often as Visiting Professor, such as Gauss Professor in Gttingen, Lorentz Professor in Leiden during the 1960s, and at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies on many occasions from 1947 onwards. Between 1966 and 1973, he was Chairman of the Commission on Statistical Mechanics and Thermodynamics of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics.

In all, he published 200 papers62 on condensed matter physics (excluding superconductivity, but including papers dealing with the connection between micro and macrophysics), 44 on dielectrics, 25 on superconductivity, 48 on theoretical physics and biology, and 21 on particle physics. In addition, he authored 2 books (one on the electron theory of metals, the other on the theory of dielectrics), and edited two others (both on theoretical physics and biology), the second at the age of 82. From 1948, Frhlich was an editor of the series Monographs on the Physics and Chemistry of Materials , published by Oxford Universitys Clarendon Press. In addition, he was Editor-in-Chief of the journal Collective Phenomena (published by Gordon and Breach), and was on the Editorial Boards of the journals Physics of Condensed Matter , Il Nuovo Cimento , and the International Journal of Engineering Science .