Its hard to imagine a glacier filling this massive basin, but it once did thatand more. As the ice meandered south approximately two million years ago, it grew to a depth of two kilometres and finally overflowed the edges of the valley. One of the remnants of this ice sheet was instrumental in creating the lakes that now fill the valley floor. In the South Okanagan, the looming cliffs above Vaseux Lake form the narrowest part of the valley. It was here that a titanic chunk of glacier created a solid, icy plug. Behind the plug, the Okanagan River, which was by that time flowing freely from the north, got backed up and formed a lake that filled the valley all the way to Enderby, one hundred and seventy kilometres away. For a time, the river changed direction, flowing north out of this new body of water, which was called Lake Penticton. But eventually the glacial plug melted and the river resumed its southerly course.

View of Okanagan Lake from above Naramata

Despite the predominance of large bodies of water, the Okanagan Valley is much more than lakes. A river also claims the valleys name. The Okanagan River rises in the northern end of the valley, near the town of Armstrong, and completes its scenic three-hundred-kilometre journey in another country, when it joins the Columbia River at Brewster, in the state of Washington. But for the most part, the Canadian portion of the Okanagan River manifests itself as a series of lakes, Kalamalka, Wood, Okanagan, Skaha, Vaseux, and Osoyoos, all linked by short stretches of the original river. The entire valley varies only slightly in elevation, from around five hundred and sixty metres above sea level at Vernon, in the northern end of the valley, to three hundred at Osoyoos, in the deep south.

Each of the six major Okanagan lakes has a unique character. KalamalkaLake of Many Coloursis precisely that: a glorious kaleidoscope of hues, ranging from a deep cerulean blue to a striking aquamarine green. Wood Lake, located between Vernon and Kelowna, is a fine place to fish, particularly for kokanee salmon. Skaha Lake has a restless, choppy character, as it provides a direct funnel for the north-south blows so common in the southern part of the valley. But its also a lake of spectacular beaches. The beach at its southern end occupies one entire boundary of the town of Okanagan Falls, and an even larger beach at its northern end forms the southern boundary of Penticton, a community that calls itself the City of Peaches and Beaches. Vaseux is a birders lake, and the quietest of the bunch, since no motorboats are allowed. Osoyoos is a lake of the south, which has the feel of a desert. But of all the lakes that grace this pastoral valley, Okanagan is the queen. One hundred and thirty-five kilometres long, with depths that reach two hundred and thirty metres, it stretches all the way from Penticton to Vernon. It dominates and defines the valley and is perhaps its greatest resource.

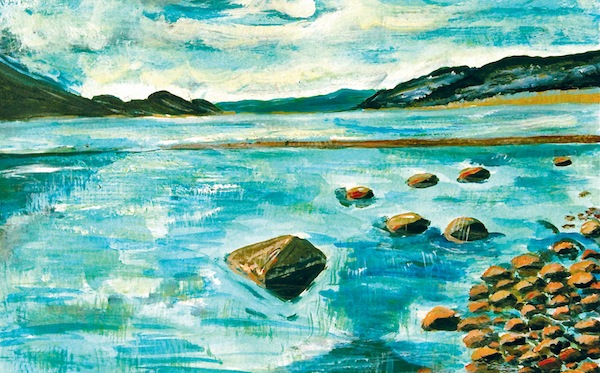

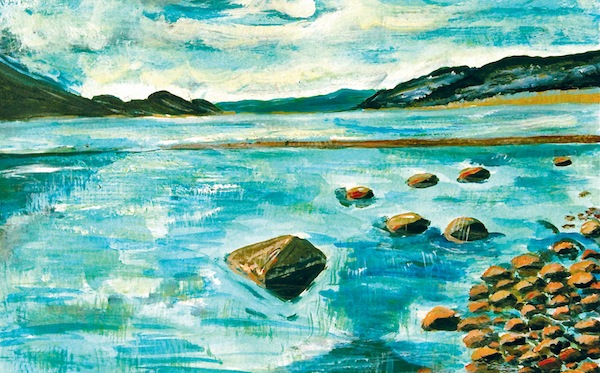

Okanagan Lake on a winters day

The region boasts four distinct ecosystems: narrow ribbons of dry grassland on the benchlands on either side of the valley bottom; coniferous forests that stretch to the mountaintops; islands of alpine tundra that cap the highest peaks; and lakes, rivers, marshes, and other water-rich habitats.

Because of its unique climate, the Okanagan Valley is bursting with riches and claims an impressive diversity of plants and animals, many of which are not found anywhere else in Canada. More than two hundred bird species nest in the many distinct valley zones: alpine birds, coastal birds, desert birds, and forest birds. Considered the most northerly extension of the great Sonoran Desert, which begins thousands of kilometres farther south in Northwest Mexico, the Okanagan Valley has places where desert sands blow in the hot afternoon winds and rattlesnakes slither among the rocky cliffs and grasslands. Merely a few kilometres away, with a rise in altitude, meadows lie smothered in alpine flowers and stunted trees cling to the ridgelines, braced against the ceaseless cold winds.

Apple blossom time

Because the valley lies in the rain shadow of the Cascades and the Coast Mountains to the west, where most of the storms originate, there is very little precipitation. The South Okanagan is the driest part of the valley, receiving only about thirty centimetres of precipitation each year. At the valleys northern limit at Armstrong, the annual precipitation rises to forty-five centimetres and the vegetation responds accordingly: Armstrong is a greener shade of green.

Okanagan Lake and Munson Mountain on a stormy summers evening (photo courtesy of the McDonald collection)

The annual parade of the seasons is a miracle in all regions of the country, but it marches to a slightly different rhythm in the Okanagan. Spring arrives early, with the first sagebrush buttercups and yellow bells and the migrating birds that move up from the southern states in late February. By late March the orchards begin to bloom. Acres upon acres of white and pink and peach blossoms fill the valley with a froth of pastels. The warm days are gentle and the cool nights refresh. By the end of June, however, the hot, arid winds are flowing up from the Great Basin Desert in the south, saturating the valley with the heat required to ripen all those peaches and grapes. Autumn is a welcome reprieve from the summer heat and brings cooler nights, golden aspens, and another flood of birds, this time winging south. Winter seeps in slowly, usually accompanied by a maddening valley fog that obscures the blue skies overhead. When snow does fall, its up on the mountaintops where, high above the fog, the sun dazzles and the skiing is superb!

The Okanagan climate is actually rather harsh, but not because of the winters. Its the summers that tax the natural world to its very limit. Spring is the season of growth, but when the hot summer winds scour the valley, the ponderosa pines, shrubs, and grasses retreat into a kind of holding pattern, guarding what little moisture theyve absorbed, waiting for the cooler temperatures of fall.