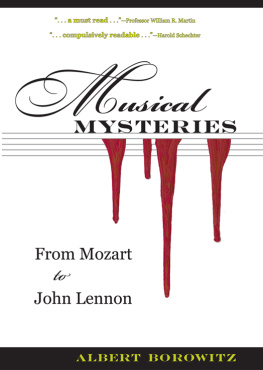

Musical Mysteries

TRUE CRIME HISTORY SERIES

Twilight of Innocence: The Disappearance of Beverly Potts

James Jessen Badal

Tracks to Murder

Jonathan Goodman

Terrorism for Self-Glorification: The Herostratos Syndrome

Albert Borowitz

Ripperology: A Study of the Worlds First Serial Killer and a Literary Phenomenon

Robin Odell

The Good-bye Door: The Incredible True Story of Americas First Female Serial Killer to Die in the Chair

Diana Britt Franklin

Murder on Several Occasions

Jonathan Goodman

The Murder of Mary Bean and Other Stories

Elizabeth A. De Wolfe

Lethal Witness: Sir Bernard Spilsbury, Honorary Pathologist

Andrew Rose

Murder of a Journalist: The True Story of the Death of Donald Ring Mellett

Thomas Crowl

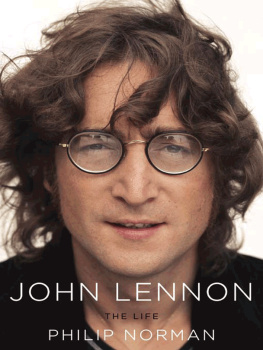

Musical Mysteries: From Mozart to John Lennon

Albert Borowitz

From Mozart

to

John Lennon

ALBERT BOROWITZ

The Kent State University Press

Kent, Ohio

2010 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2009047059

ISBN 978-1-60635-026-3

Manufactured in the United States of America

Pore Jud is Daid: Violence and Lawlessness in the Plays of Lynn Riggs and Lamech, the Second Biblical Killer: A Song with Variations were first published in Legal Studies Forum. Lully and the Death of Cambert and Gilbert and Sullivan on Corporation Law: Utopia, Limited and the Panama Canal Frauds first appeared in Albert Borowitz, A Gallery of Sinister Perspectives: Ten Crimes and a Scandal (Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univ. Press, 1982), and are reprinted here with permission. The Stalking of John Lennon first appeared as a chapter in Albert Borowitz, Terrorism for Self-Glorification: The Herostratos Syndrome (Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univ. Press, 2005), and is reprinted with permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Borowitz, Albert, 1930

Musical Mysteries: From Mozart to John Lennon / Albert Borowitz.

p. cm. (True crime history series)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60635-026-3 (hbk.: alk. paper)

1. Music and crime. 2. Crime in music. 3. MusiciansDeath. I. Title.

ML3916.B6 2010

780.0364dc22 2009047059

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of

Jonathan Goodman,

generous friend

and

master of crime history

Contents

Preface

Since this volume is entitled Musical Mysteries, I should begin, as old-fashioned music used to do, by clearly announcing the principal themes. In my discussion (in ) of the encounters of musicians with homicide, real or suspected, I will be emphasizing three recurring motifs. The first will be envy and competition between musicians. The second theme will be in the form of a question: Can genius and criminality coexist in the same soul? And finally a third theme will keep cropping up like a rondo subject: the jarring contrast between the sublime activity of the creative artist and the violent melodrama of everyday life from which none of usmusicians includedis safe.

Let us begin with theme one, envious and competitive musicians. Who was the first of them to suffer the pangs of rivalry gone mad? If we were to urge the claim of Antonio Salieri to this sinister distinction, we would be many millennia too late. Perhaps the earliest example of a composer-performer who turned to murder to eliminate a competitor was the very inventor of the musical arts, the god Apollo. This well-known story has a Mozartian ring for it features the first magic flute, a double flute that Athena made from a stags bones and played at a banquet of the gods. She was nettled to see that Hera and Aphrodite were laughing at her behind their hands while all the other gods seemed quite transported by the music. After the concert she went away by herself into a Phrygian wood, took up the flute again beside a stream, and watched her image in the water, as she played. Immediately she understood why the two goddesses had laughed at her. Her efforts on the instrument had turned her face an unflattering blue and caused her cheeks to swell. In disgust she threw down her flute, and laid a curse on anyone who picked it up.

The unfortunate victim of Athenas spell was the satyr Marsyas. No sooner did he put the flute to his lips than it played by itself, reproducing Athenas divine music. The satyr, though, claimed the music as his own and wandered through Phrygia enthralling the peasants with his performance. They told him that even Apollo couldnt do better on his lyre, and Marsyas was foolish enough to accept their critical appraisal. His vainglory provoked the anger of Apollo, who invited him to a music contest, the winner of which should inflict whatever punishment he pleased on the loser. Marsyas consented, and Apollo impaneled the Muses as a juryas clear a fix as there ever was at least before the judging scandals in modern Olympics. The Muses claimed to be charmed by both instruments until Apollo came up with a trick. He challenged Marsyas to do with the flute what the god could do with the lyre. Turn it upside down, he ordered, and both play and sing at the same time. Marsyas failed to meet this tall order, but Apollo, with ease, reversed his lyre and sang... delightful hymns in honour of the Olympian gods. The Muses awarded victory to Apollo. Thereupon the god took cruel revenge on the musical upstart Marsyas. He flayed him alive and nailed his skin to a pine tree.

If the divine creator of music could be moved to murder by envy of a mortal competitor, how was more restrained behavior to be expected from Salieri and his ilk? My article, Salieri and the Murder of Mozart, published seven years before Peter Shaffers Amadeus, explores not only the envy motif but also the psychological compatibility of genius and crime. A classic (but optimistic) pronouncement on the latter subject is attributable to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart himself, not, however, as he appears in Shaffers drama but in the pages of Alexander Pushkins chamber play Mozart and Salieri. A seventeenth-century analogue to the whispering campaign against Salieri was the assertion that opera composer Jean-Baptiste Lully, after driving his rival Robert Cambert out of the French theaters, murdered him in England.

The claims that homicide caused the deaths of Mozart and Cambert are ungrounded, but the mysterious murder of eighteenth-century composer and violinist Jean-Marie Leclair is well documented by surviving records of the police investigation. The solution to the case that I propose on the basis of my examination of the detective work suggests that the killing of Leclair was inspired by envy and a sense of frustration over the failure of musical ambition.

The third theme of of Musical Mysteries will show musicians trapped in lurid events of everyday life, in tales of homicide more suited to the Police Gazette than to the Musical Quarterly. In these true stories the musician appears as vengeful husband or as victim of a mistresss former lover. Perhaps the greatest musician to have figured as murderer in a domestic tragedy was the madrigal composer Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa. In 1586 he married a noble Neapolitan lady, Donna Maria dAvalos. Four years later, having learned of her love affair with the Duke of Andria, he had her murdered by servants and himself took an active part in the killing. A century later another Italian composer, Alessandro Stradella, became as famous for amatory scandal and tragedy as for his music. After eloping with the mistress of a Venetian nobleman, Stradella was wounded by assassins sent from Venice. But he did not change his ways. Another group of avengers, apparently in punishment of a later romantic escapade, murdered Stradella in 1682.

Next page